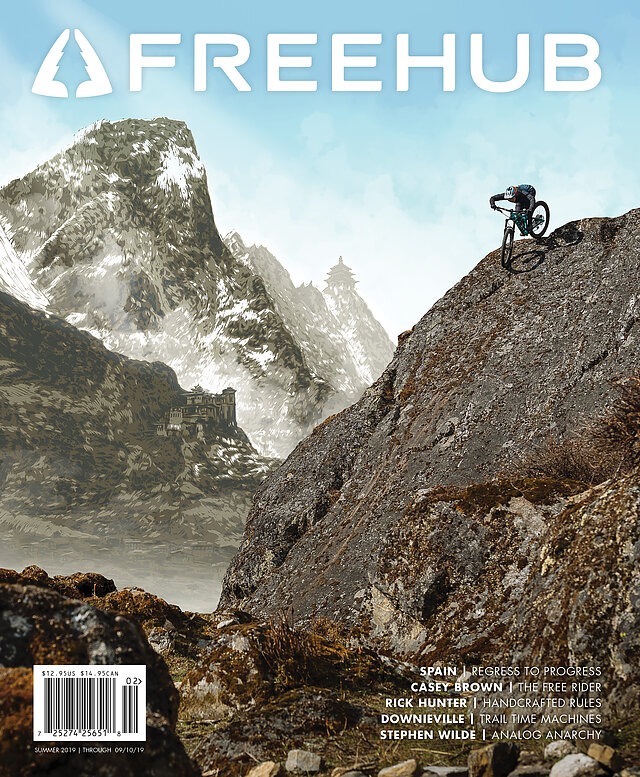

Welcome to Issue 10.2

Mountain biking was born through wanting to pushing the limits, and—not surprisingly—that trait has remained at the center of the sport. Photographer Stephen Wilde experimented with his camera and chemicals in the darkroom, while Rick Hunter has long questioned what bikes can look like—and do. As Casey Brown searches for her limits, she progresses the sport’s. From Downieville, California to Spain’s Basque Country, the value and impact of a community is being continually redefined. In Issue 10.2, we celebrate the people and places that have little regard for the status quo.

At first glance, the thick concrete walls and tall metal gate surrounding Campo Bici don’t give much away.

They suggest more fortress than fun, and it’s hard to believe we’re about to visit a bike school. As we approach the entrance, though, the unmistakable sound of children’s laughter fills the air, softening the compound’s hard exterior. One step onto the property and it feels as if we’ve been transported to a different time and place, a bicycle oasis gradually revealing itself.

Perched on a hill at the outskirts of Quito, the capital of Ecuador, the property overlooks the city center and all the sprawling density we passed through to get here. It seems as though we are woven tightly into the fabric of the city, yet somehow isolated in our own little bubble. Chickens and dogs patrol the grounds, which feature an orchard of citrus trees and a bountiful vegetable garden. And then there is the main attraction: a large, well-manicured pumptrack, complete with dirt jumps. We eagerly grab our bikes for a few laps before the sun drops behind the surrounding mountains...

Words by Thomas Vanderham | Photos by Ross Bell

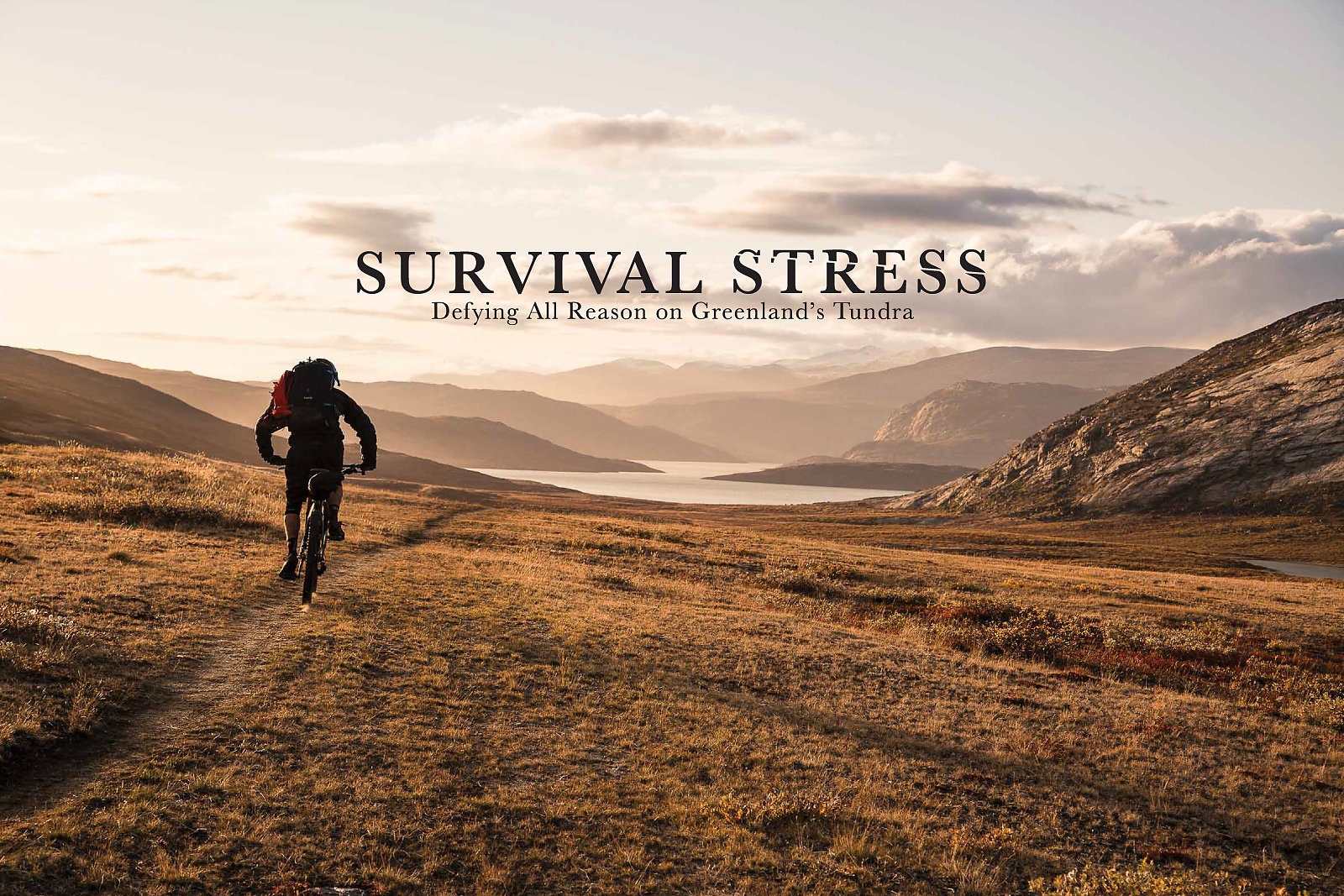

What’s the point of stress?

Not the forgot-to-pay-the-phone-bill or missedyour- girlfriend’s-birthday kind of stress (not that those aren’t important), but that life-or-death primordial stress.

I can honestly say I was stressed out when I took this self-portrait. It was about 8 p.m. on the third day of a bike traverse in the Greenland backcountry, and I had been on the move for 13 hours. The last thing I wanted to do was set up my camera for a photo, but the opportunity was too good to pass up.

I was alone on a 125-mile, point-to-point crossing of a route that, to my knowledge, had never been attempted on a bike during the snow-free months. I had found some semblance of a trail pounded into the tundra by reindeer hooves, but the terrain still consisted mostly of soggy bogs and mechanical-bull-style rock gardens. It had taken me four hours and a lot of swearing to navigate through a half-mile-long talus field earlier that day. It was mid-September, so I was losing 20 minutes of daylight every day to the encroaching winter and the mercury was dropping to 20 degrees Fahrenheit at night. My 30-degree sleeping bag was no longer cutting it...

Words & Photo by Ben Haggar

Described as rough, brutal, grueling and even savage, the annual five-stage, one-day Crankworx Whistler enduro race is notorious for being one of the toughest enduro contests on the planet.

The race, now in its seventh year, crams relentless descents with sustained climbs, tinder-box heat and rootfilled tracks—all framed by the ancient Coast Mountain forests and throngs of international spectators.

It’s a maker of legends, both in terms of athletes—Jesse Melamed, Cécile Ravanel, Martin Maes, Jared Graves and Jerome Clementz—and trails, giving broader prominence to descents such as Top of the World, Microclimate and Ride Don’t Slide. It’s also one of the only races to grace the Enduro World Series (EWS) circuit every year since the venerable series began.

But when the EWS was first revving up and the inaugural Crankworx Whistler race was being established in August 2013, planners in North America were still trying to determine how to run a proper enduro race...

Words by Claire Piech | Photos by Sven Martin

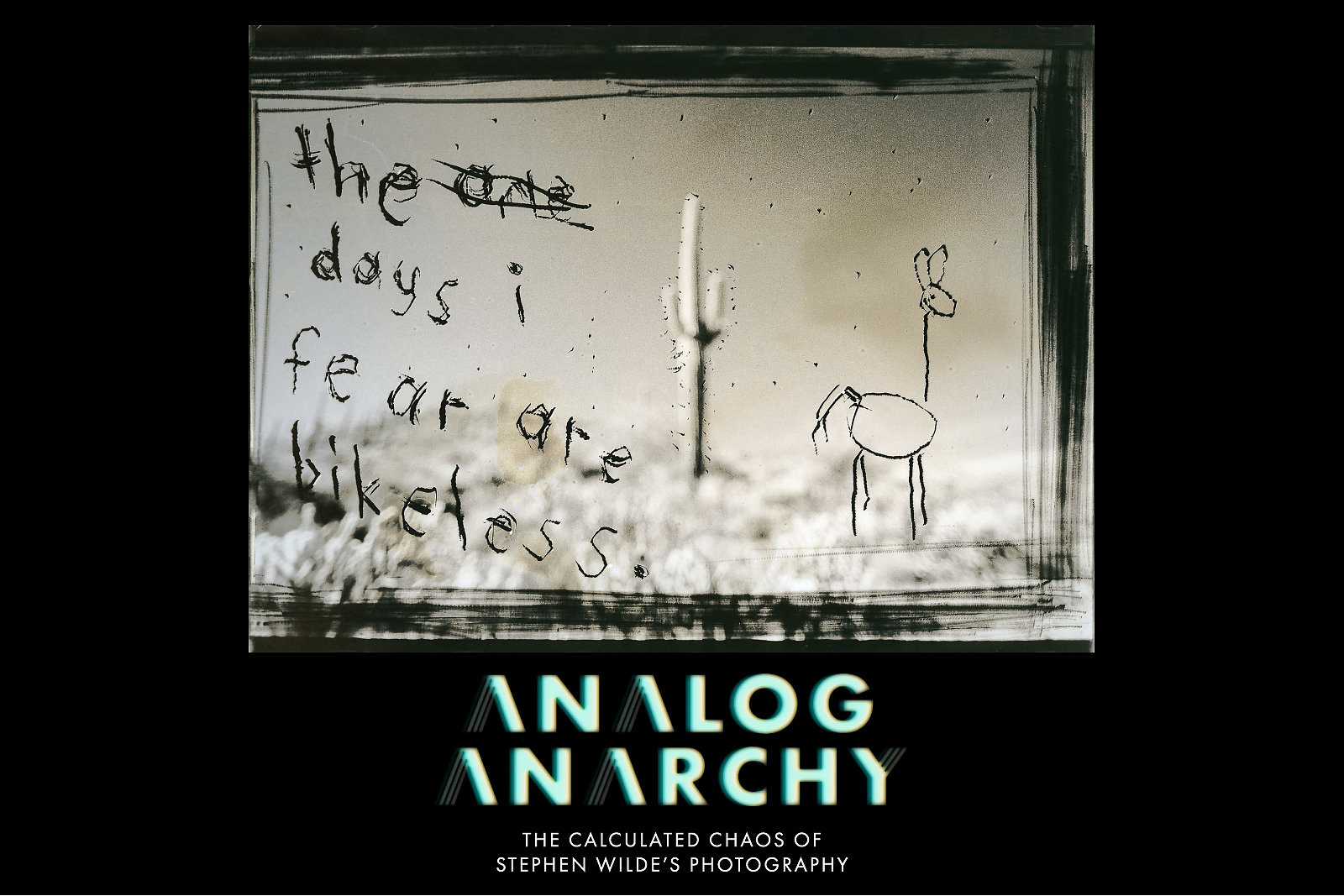

In today’s fail-safe world of digital photography, few things feel risky—and even fewer things feel truly dangerous.

With LCD screens constantly flashing back images for immediate review, it’s easy to repeat shots until the desired result is achieved. Photographers no longer need to rely on their intuition, on that proverbial “sixth sense,” to know when they’ve captured the perfect moment.

Gone are the days of rushing to the darkroom to develop freshly exposed film in anxious anticipation of what would appear on the other side. The stress of shielding lead-lined film containers filled with the irreplaceable gems of a once-in-a-lifetime assignment—and of keeping them from airport X-ray machines at all costs—is mostly a thing of the past.

These days, it’s hard to actually fail, and outcomes can feel predictably routine. Post-processing options are swapped with the click of a mouse, salvaging even poorly executed shots by readjusting exposure levels. The breathless seconds of pulling negatives from chemical baths are distant memories for most...

Words by Brice Minnigh | Photos by Stephen Wilde

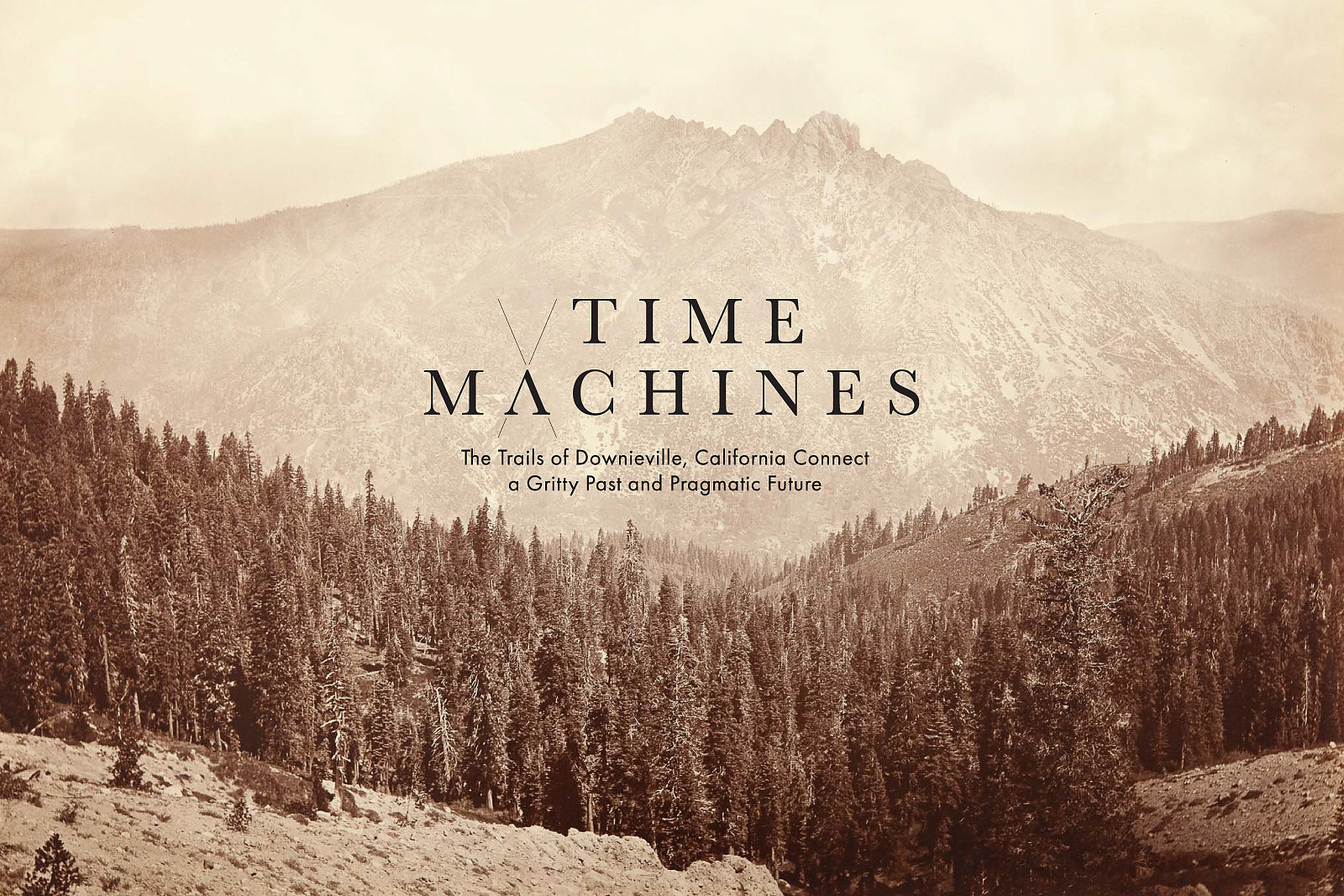

For a town of 325 citizens, Downieville, California, is home to a lot of ghosts.

They wander through the 150-year-old buildings lining the scrap of downtown; they haunt the 7,000-foot heights above, silently chipping away in the ruins of countless tunnels from one of California’s most prolific mining booms. They fish the banks of the three rivers that collide at the center of town, pulling in equally ethereal river trout. They chop and saw away at trees of primordial size, many of them destined for mine shoring, bridge abutments, or railway beds.

A decade ago, it seemed as if Downieville would become a ghost itself, rotting then fading from Northern California’s treacherous topography like so many other mining or timber towns. And it would have, if not for one spectral thread: In the Lost Sierra, the ghosts all built trails. Generations after their creators are gone, a group of passionate inhabitants are using those trails to breathe renewed life into a 300-person town that was once home to 5,000.

Born from a maxed-out credit card, a van and one chainsaw, fueled by mountain biking’s rowdiest race, and shaped by a grassroots organization’s unintentional vision, Downieville’s newest trail builders are determined to keep the town away from the afterlife by creating something that will last for generations...

Words by Sakeus Bankson | Photos by Ken Etzel

Standing in the middle of our dust-covered campsite, feeling shattered from another long day of blasting down treacherous scree slopes, we stared across the barren gorge at a lone figure perched atop the mountain in front of us.

The wind had been howling all afternoon, and we were anxiously hoping for a sustained lull as the sun’s rays waned on the horizon.

For four evenings running, I’d negotiated that precipitous boulder-funnel on my way back to camp, alternating between controlled slides and slow-speed washouts in a purposefully diagonal traverse to the creek bed below camp. Every time, I wondered what it would take to straight-line that rock-choked chute from top to bottom. If the wind would just subside, that solitary silhouette gazing down at us could give me my answer.

I jumped as my walkie-talkie crackled, heralding a voice of disarming composure: “I think the wind’s died down enough. I’m ready to drop when you are.”

“Ten-four,” I responded, pausing momentarily to ensure the cameras were recording. “We’re rolling.”

Words by Brice Minnigh

I’m sitting in the Bonny Doon, California, home of Rick Hunter, the reclusive—some would say reluctant—custom bicycle builder.

At my request, Hunter has pulled out a bunch of old personal and brand-related stuff for me to look through. His eight-person dining table is covered with archival bits: concept drawings, to-do lists from more than a decade ago, race numbers, those post race photos stamped with a copyright we’d receive in the mail with offers to buy finished prints, and no shortage of old magazines, now long out of print.

It’s been 20 years since British mountain bike journalist Chipps Chippendale’s The Outcast singlespeed fanzine was printed, with a cover blurb reading, “The untrendy end of the bicycle world… .” Hunter picks up the zine, which contains, unlikely though it seems to me, a fictional story he wrote called “The Rider.” He agrees to let me record him reading the short story, and we kill the sound from the scratchy vinyl of 1980s skate-punk band Jodie Foster’s Army that’s been blaring in the living room so I can get a clean recording...

Words & Photos by Brian Vernor

Low-hanging bushes whip me in the eyes as I lay my bike over into the next turn.

The sun set at least 30 minutes ago behind the high plain on which Madrid sits, but it’s still 95 degrees Fahrenheit. I’m desperately trying to follow Sergio Layos, a Madrid local and one of the BMX world’s most stylish and longest-serving athletes, down a bobsled-style trail that rockets through a park just outside the city center.

Layos is relatively new to mountain biking, even though he’s usually out of sight four corners into a descent. But he’s already uniquely enmeshed in the culture, as two of his best friends are integral to the region’s scene. One is Igor Eskudero, a lifelong mountain biker and BMXer who works as a guide for Basque MTB, based in the north of Spain. The other is Ricky Grimal, another BMX ripper who lives in Barcelona and has played a big role in the design, development and growth of the world famous La Poma Dirt Jump Park...

Words & Photos by Cal Jelley

Subscribe in print

or online today to continue reading!

or online today to continue reading!