In Good Company Harvesting Thrills on the Sea to Sky Corridor

Words by Seb Kemp

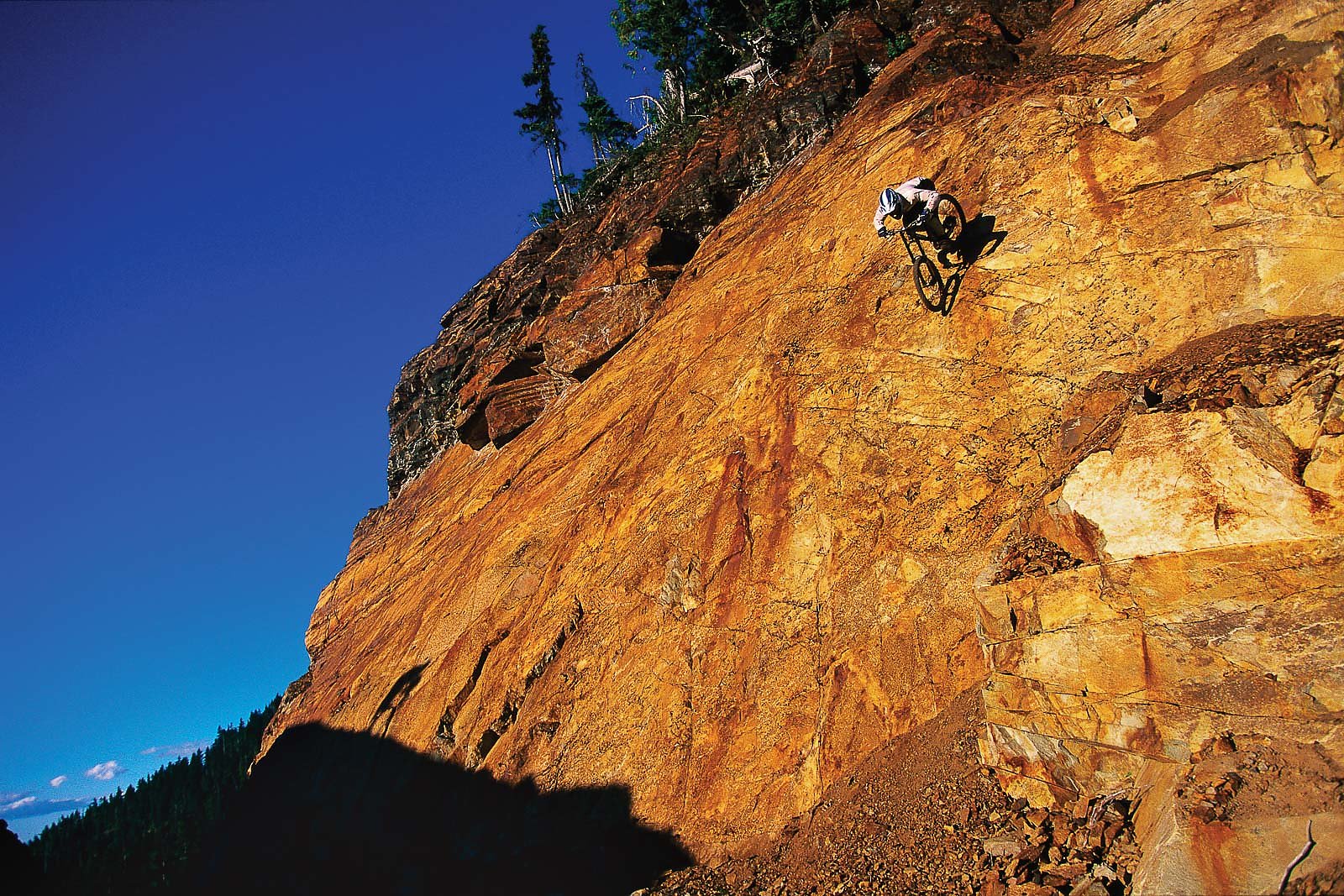

To understand mountain biking in the Sea to Sky Corridor, you have to understand two things about the trails here: First, the nature of the terrain makes progress and momentum hard fought and hard earned.

Second, almost every trail was built on the flesh and bones of men, by the egos of boys with their toys.

The four communities that make up the Corridor—North Vancouver, Squamish, Whistler and Pemberton—are a chain of pearls strung along the rolling blacktop of Highway 99. This cluster of settlements is home to hundreds of miles of mountain bike trails, as well as a truly inspiring network of riders, builders and advocates to match.

In the Coastal Range, the valleys are steep, deep and unrelenting. The combination of immense geological forces and erosion have left almost no flat surfaces, and every foot of elevation gain is hard-fought and easily lost. Trails are strung precariously across mountainsides, following the path of least resistance, which often means straight up or straight down. The huge trees can simultaneously cause both claustrophobia and vertigo. It’s far from the easiest location to build.

And yet this is the epicenter of not just Canadian mountain biking, but also modern mountain biking as the world knows it, earned through the obstacles-be-damned attitude of multiple generations of builders. Unlike many other renowned mountain biking destinations, there are few horse trails, old trade routes, or even motocross networks. Almost every trail was built during the past 30 years, by mountain bikers, for mountain bikers.

As a result, the trails don’t take you from A to B. Their objectives are making the most of every feature, or snaking around the sections of unrideable terrain (although in the Sea to Sky, “unrideable” is a very relative term). In general, they don’t give cheap thrills. Instead, they ask for sacrifice, whether in blood and bone, tenderized muscle or battery-acid-filled lungs. They can beat the dignity out of first-time visitors, and even the most experienced can be humbled quickly. But riders almost always come back, stronger and sharper and ready to relish the fight.

On the North Shore of Vancouver, employees of the Deep Cove bike shop were the first to pioneer rides along the existing roads. But the ones who would define the North Shore’s style were folks like Todd “Digger” Fiander, Ross Kirkford, Jim Leppard, “Mountain Bike” Mike, “Goat Legs” Gabe and “Dangerous” Dan Cowan, among many nameless others. Their trails, hidden in the shadowy forests, would make the area infamous—and then famous—on the larger mountain biking scene. “Build it sick, build it high, build it skinny” was the mantra during those early, secretive days, but it was also about steep and deep lines between the area’s towering cedars. And it still is.

Now the focus on the Shore is stewardship and conservation, and at the forefront is the North Shore Mountain Bike Association (NSMBA), led by Trails Manager Mark Woods. Working with local government and authorities, NSMBA has harnessed the ponderous energy of the mountain bike community in Vancouver, preserving the past and building wisely for the future—guaranteeing “the Shore” won’t go the way of the countless rotting skinnies and ladders twined through its trees.

Farther north, in Whistler and Squamish, mountain bike culture was built largely on gears and gasoline. As late as the 1980s, bicycles were limited to dirt roads and walking paths. And then came the throttle and chainsaw-assisted actions of Jon Anderson, Bill Epplet and then Dan “Danimal” Swanstrom, whose work on moto trails in the area opened a whole new world. Mountain bikers began creeping down the moto up-trails, riding the trails so often eventually their moto origins were forgotten.

The gas-powered, downhill-oriented trend continued as the ski resort began running chairlifts in the summer—and whisking bikers to the top in the process. Over the next 15 years, what started as burning V-brake pads while skidding down fire roads has blossomed into the colossal playground that is the modern Whistler Bike Park. The present-day Whistler Bike Park defines an entire shift in contemporary mountain biking, one that has set the blueprint for all others to follow.

While the bike park may be the most obvious fixture in Whistler, a ferocious amount of energy is being put into developing trails in other parts of the valley. Due to the nature of land ownership and land use in the province, much of it is rogue. But there is a growing acceptance that if mountain bikers want the best trails—and want those trails to stay—they must be willing to play ball with everyone involved.

It’s an ethos many builders have adopted. Ted “Big Red” Tempany, owner of Dream Wizards, has been pumping out mile after mile of world-class riding surface, using his quiver of digging machines (his favorite is the “Honey Badger”). Using hand tools and a chainsaw, Dave Reid has put in more trail than should be possible for one man. Zander Strathearn, Tim Haggerty, Jerome David, Dan Raymond, Ian Kruger, Jonny “Foon” Chilton and Seb Wilde are all names as well known in the region as the many trails they’ve built. And yet so many more have contributed so much.

And that’s the point. While the Sea to Sky may appear to be comprised of four neighboring towns, it’s actually one extended community of mountain bikers, able to hop next door to borrow a cup of sugar as required, to sample something specific in the use of terrain, or harvest thrills according to the seasons. Everybody in these towns, whether they’re here for a holiday or a lifetime, is consumed by passion for bikes. If your heart beats to the pedal stroke, then you are in good company.

I only truly became a resident once I recognized the interconnectivity of the riders, the trails and communities here, not just using each area for my own enjoyment, but also offering some sweat equity in return. My daydreams are filled with memories of riding loamy rollercoasters, following a line of friends in the golden light of a summer evening—the work of boys with their toys, enjoying three decades of blood, sweat and gears.