At first glance, nothing is special about the sign.

The brown paint is faded and chipped by weather and age, and the letters are more bleached wood than the original yellow. Just another United States Forest Servise “point of interest” marker, with directions for the Continental Divide Trail listed below.

I’m a history nerd and love these things, and so read the board’s information aloud to the group: photographer Paris Gore, rider Mike Hopkins, Brandon Watts and Chris Grundberg. We are on Montana’s Lewis and Clark Pass, which Meriwether Lewis used on his return journey from his and William Clark’s famous cross-continent expedition.

It is Paris who noticed the date on the sign: July 7, 1806. It is currently early July, and more out of curiosity than anything else, Mike looks at his watch.

July 7, 2015. Lewis, one of the greatest explorers of all time, returning from one of the greatest expeditions in history, had passed over this spot 209 years before to the day.

Lewis used horses and wagons, had traveled hundreds of miles, and had hundreds more ahead. We are on high-end trail bikes, have come a mile and a half, and have 25 miles to our destination. But it is still a serendipitous connection, carbon or wooden wheels aside. It adds a bit of depth and meaning to our three-day bike-packing adventure, motivating us in the cold, now-raining morning. We’ve even heard the ruts we’d climbed supposedly followed Lewis’ original path.

It was almost impossible not to marvel at such a hardy generation of explorer, and we wondered what Lewis and Clark would have done had they possessed the fancy gear we now carried. But one thing was certain—they wouldn’t spend their time standing around, and so we pushed off and continued along those 200-year-old tire tracks.

Highway 12 cuts through the middle of Lincoln, MT, and is bordered on both sides by a four-wheeler track nearly as well-used as the pavement. With a population of just more than 1,000 people, the town consists of a small grocery store, a few bars, a liquor store, a gas station, a taxidermist and the Bootlegger Casino, a dubious-looking establishment that could currently be open or completely abandoned—it’s hard to tell from the faded billboard and half-broken neon.

Lincoln provides some of the best access to much of the Helena National Forest, which is well-known for its hiking, fishing, hunting, horse-packing and, in our case, bike-packing. At the gas station, the flurry of trucks towing dirt bikes and quads attests to its recreational reputation.

Lincoln also has a more infamous claim to fame, as the spot where Theodore J. Kaczynski—more commonly known as the Unabomber—was finally captured in 1996. Welcome to Montana.

We pulled off the highway onto a gravel road, weaving through a random assortment of cabins and large shop buildings until we arrived at our destination: a single-wide trailer built out into a rough-looking cabin, tucked into a stand of ponderosa. Two men huddled over a grill: Emmett Purcell and Pat Doyle, the folks behind the trip.

Pat—the face of Bike Helena (he now works for Montana State Tourism)—offered us beers with a hearty handshake. Emmett, trail coordinator for the Prickly Pear Land Trust, took a break from the fajitas to welcome us warmly.

The plan was to have a local horse packer carry our water, food and bedding into strategically placed campsites. As we talked over specifics, we crammed the necessary supplies for the next day into our too-small packs—everything but our bedding and water jugs—and fajitas into our mouths. We were headed to a fairly obscure section of the CDT, which Pat and Emmett pointed out on a map laid out in the grass.

Packed, full and informed, we drank one more beer, threw our sleeping bags out on the lawn, and fell asleep under a clear, starry sky.

For horse-packing guides in Montana, the days start early.

We awoke the next morning at 4 a.m., stars still the only light in the bruise-black sky. We were headed to the Alice Creek Trailhead, where we were to meet our four-legged potential accompaniment. The murky, predawn haze was just light enough for us to catch some wildlife alongside the dirt road on the way to the trailhead. By the time we met Dennis Milburn in the parking lot, the sun still hadn’t broken the horizon.

Dennis greeted us with a firm handshake and a heavily mustachioed smile, a Stetson capping his graying head. As the local agency liaison to the Helena Backcountry Horseman, he’s one of the main voices for bike/horse relations in the area. We were somewhat disappointed to note the lack of horse trailer in the lot, but Dennis explained there just wasn’t enough water for the horses—the summer had been a dry one.

Horses or not, Dennis was a valuable resource. Unlike the majority of the country, relations between horse riders and bikers in the Helena area are cordial—and cohesive, as both groups are staunch advocates of trail building and maintenance. Most local bikers know and respect proper horse-trail etiquette, and conversely horse riders work alongside bikers in dealings with the USFS and local government agencies. The two groups may not be besties, but Dennis and Emmett obviously know each other well. Dennis did wake before 4 a.m. to meet us, and he apologized for not being able to help pack our supplies to camp. I’d call that friendship.

As the sun started to crest the horizon, Dennis and Emmett wished us off, and we strapped a few final items to our bags, topped off our water, and began the short-but-steep climb. Lewis and Clark Pass is the only road-less pass on the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail, and despite also being a thoroughfare for the 3,100-mile Continental Divide Trail, the path to the top is faint. Considering only 200 people attempt the trail annually, it’s not much of a surprise.

The pedal took us through a huge valley of grassland, dotted by subalpine fir and creased in the middle by a pine-protected creek. Cairns and occasional traces of a rutted two-track are all that marked the top section, eventually topping out into a scrubby pine forest. By the time we reached the pass, dark clouds and a cold wind had moved in, and soon it began to mist, then drizzle. When we arrived at the top it was pouring—a testament to the fickle and extreme weather of the area, even in the depths of summer.

Then we spot the sign, and Mike notices the date. Rain didn’t stop Lewis, and so we decide it sure as hell won’t stop us.

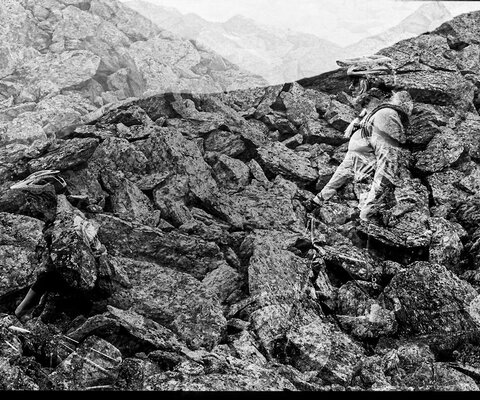

With enough fog any location can feel mysterious, but when it’s along bare ridges, broken by clumps of dark rock and the occasional huddled pine, it conjures images of the Scottish Moors. We spend the morning climbing into the wet whiteness, rock slides and ghostly arboreal skeletons appearing out of the mist. The trail grows faint on the particularly windswept sections, disappearing entirely in the glistening stretches of tumbled basalt. This is the CDT, one of the most famous trails in the country, and from our limited surroundings we could be in the farthest corner of some remote wilderness.

The same primitive conditions also make for perfect adventure riding. The soft dirt corners allow us to dig in like we’re riding uncut Pacific Northwest loam, and the gritty texture of the rocks means we have traction even in the rain. The wind tears at our coats as we re-ride a few particularly delicious stretches. One section snakes down an open face before diving down a steep, skiddy scree field, and we spend an hour hiking and shooting. The beauty of having short days—we have 12 miles to cover—is you can stop to enjoy the details.

Still, the entirety of those 12 miles hangs at about 7,000 feet, which is difficult for PNW lowlanders like ourselves. The vicious weather doesn’t help. Where possible, the trail follows the Continental Divide meticulously, dipping and climbing from mini-summit to mini-summit. At one point it dives into a burnt-out forest from a long-ago wildfire, and becomes nearly nonexistent under downed logs and tall grass. We get lost multiple times, but push onward. Even the scorched skeleton pines provide some entertainment, as Mike and Brandon rip a corridor through their ghostly trunks.

The day’s ride culminates on an unnamed 7,500-foot peak. The dirt has turned to deep orange and the ridgeline is now covered with loose shale, which seems bent on dinging our bottom brackets. Mike takes a rock to the shin, and we suffer multiple flats and a torn tire sidewall. It’s surreal riding, but it comes at a price.

We finally drop toward our last stretch of the day, a saddle called Cadotte Pass. It’s a huge plain, and contains the first signs of civilization since we left the sign—a powerline and a few private cabins. Rumor is that Cadotte is the location of one of the first UFO sightings in the United States, recorded by a fur trapper in 1865, and the yurt on the other side of the valley looks somewhat extraterrestrial on the pass vast ochre expanse. We’re able to let off the brakes and scream across, not even bothering to search for the now-invisible trail. A small figure stands next to the yurt—Emmett—which means camp and dinner are close.

To call Emmett “energetic” would do the short, dark man an injustice. His excitement about his lifelong hometown of Helena is nearly overwhelming, matched only by his passion for biking in general. He’s been involved in the local trail scene for decades, and remembers riding these trails years ago on both old-school downhill bikes and hardtails (he hasn’t ridden them much since, which has led to some of our route-finding confusion). With the assistance of two interns, he has taken the place of the horses and biked in our sleeping supplies and 10 gallons of extra water. He barely stops to breathe as he hikes alongside us on the final pitch to camp.

It’s on a lightly forested ridgeline, and while the weather clears for a dinner of rice, soup and chocolate, dark clouds boil on the horizon. Using downed logs and branches, we channel our frontiersmen skills and construct shelters under the trees before sharing one final sunset beer. Then it’s into our shelters. A storm is coming.

We wake to clear skies and wet grass, and nighttime memories of rain, clouds and frigid temperatures fade in the hot morning sunlight—ironic, as we’re headed to Rogers Pass, the location of the coldest recorded temperature in the United States outside of Alaska. On Jan. 20, 1954, it hit -70 degrees Fahrenheit. Today, July 8, 2015, temps are forecasted to top out in the mid-90s.

Our intern sherpas spent yesterday caching our supplies and water along the route for the day, and so after a breakfast of oatmeal and instant coffee, we pack up our gear for the descent to Rogers. Emmett has brought his bike as well, and he bombs down loaded with a massive, clanking pack. The trail switchbacks through a vibrantly green forest, alternating between fields of wildflowers, stands of fir and loose rock and shale. The final section even cuts between a few cliffs—the CDT is nothing if not varied.

Emmett has parked his camper-van-equipped Dodge Sprinter alongside the highway, and we feast on beer, chips, soda and PB&J bagels. The previous night Emmett had joked about whiskey and beer at the next camp, and we wax longingly as we sip some local double-malt to prep us for the long ride ahead.

Naively, we thought the trail was primitive yesterday. Today, we lose it almost immediately, gaining the first pass via a game path that requires carrying bikes on our backs. The views make up for the struggle, and the following riding goes from incredible to all-time. It winds along cliffs, across massive alpine scree slopes, down knife-blade ridgelines and even on some slick rock. We spend an hour on a section reminiscent of Moab’s Porcupine Rim, then another hour on stretch pulled from Fruita’s Zippity Doo Da. The trail fades in open stretches, allowing us to freeride down to the saddle bottoms.

The sun is brutal, however, as is the shale and loose rock—we suffer even more flats than the day before, and I blow out another sidewall and am forced to MacGyver a patch out of a dollar bill and some glue.

Keeping with Emmett’s tradition of underestimating distances, the 14-mile day stretches on as if it were double that length. Still, the gauntlet of zones pulled from across North America continues—Cascade Mountains-esque meadows go to British Columbia forests and back. One section of ridgeline even has sideways pine trees, their 30-foot lengths forced to the ground by wind.

Up and down, up and down. The hours pass until we are all exhausted and ready to be finished, despite the incredible quality of the riding. By the time we make the final descent, possibly the most technical of the day, we are all in survival mode, desperately navigating the steep, loose trail through stands of ponderosas. It’s the definition of too much of a good thing, and by the time we reach the pink flagging marking camp, we’re just trying not to die.

Emmett may not be the best judge of distance, but he does know how to pack a supply cache. True to his word, the stash includes two plastic bottles of whiskey and three six packs of beer, and we immediately bust into the pilsner. The first is a recovery beer; as we all down our second, we lay back in the pine needles. By the third beer and our first pull of whiskey, we’re reminiscing about the day, the difficult parts forgotten in favor of all the incredible ones. And there are plenty.

A duo of CDT hikers show up just as we’re preparing to set up camp, and we move farther into the woods so as not to disturb them with our excited chatter and libations. It’s a reminder of the relatively peaceful relations along this section of the trail, and that we are only experiencing a tiny fraction of what it has to offer—25 miles down, 3,000-plus to go.

Dinner is a massive pot of mac and cheese, accompanied by more whiskey and beer, a delicious end to a difficult day. Talk fades as exhaustion sets in. We have only a short climb in the morning, but we’ve suffered through plenty of long ones already.

Flesher Pass is nearly 1,000 feet from our perch, the descent of which we intend to savor. The previous night’s final section was particularly spicy, and we push a short distance up to enjoy it somewhat fresh and without packs. After a few laps we load up—without Emmett, we all have items dangling from the sides of our bulging packs—and leisurely make the final pedal.

The traffic along Highway 279 is hidden by trees, but is audible as we drop in toward our destination. The last bit of trail is short but extremely fun and fast, smooth, flowing dirt through a beautiful pine forest, made treacherous by the ponderous packs on our backs. Still, when we rattle down the final staircase and out onto the pavement I decide the bottom comes too fast.

Across the highway is another giant “point of interest” sign, this one emblazoned with “Fleshers Pass and the Continental Divide” in shiny brown-and-gold paint. It’s the official end to our nearly 30-mile journey.

Talk turns to beer and food—an hour later, we end up stopping at an incredibly Montanan restaurant called the Grubstake. But my eyes keep drifting toward the next section of the Continental Divide Trail, and I can’t help but wonder: What would Lewis do?