Welcome to Issue 15.1

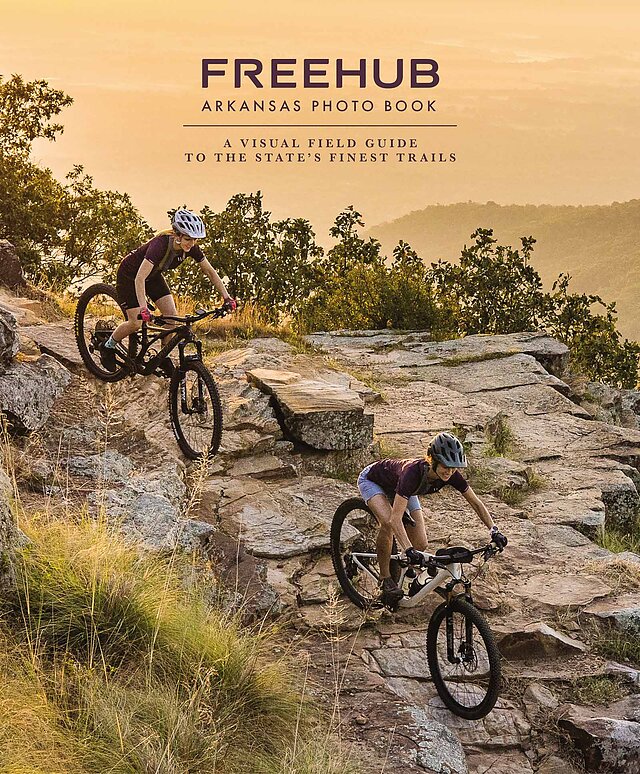

Northwest Arkansas’ trail expansion over the past decade is well documented. Much less so is the state’s mountain biking history, which long predates the modern boom of flow trails and easy-to-access singletrack hubs. To kick off our 15th anniversary of independent publishing, Freehub is proud to present the Arkansas Photo Book, a visual field guide and in-depth journal that digs through the rolling Ozark and Ouachita ranges to unearth the Natural State’s storied fat-tire past. Each page adds another layer in understanding how Arkansas grew to become such a notable destination for mountain bikers. From the rocky slopes of Mount Nebo to the twisting labyrinths of Bentonville and Fayetteville, standout trails are outlined in tandem with influential community members working tirelessly to firmly stamp Arkansas as a model for how to build a buzzing bike culture. Grab a copy of 15.1 and plan your own adventure.

Arkansas plays a trick on first-time visitors arriving from the East. The roads, dead flat and straight, lull newcomers into believing this lack of geological diversity will span the entire state. Then, just beyond the Arkansas Delta farmlands, the gradual ascent from the Mississippi River Valley to the peaks of the American West begins.

In these foothills of the Ouachita and Ozark ranges, an array of wetlands, rolling timberlands, and pockets of canyons and snaking valleys dot the land. Rivers, large and small, meander to the Mississippi River.

These mountains, which exceed 300 million years in age, are among the oldest of the American landscape. Although inhabited for more than 10,000 years, European explorers began settling in the 1500s. And while the mountains of “The Natural State” do not scrape the skies like the towering Rockies or the mighty Sierra Nevada, their deep hollows create hideaways where an adventurous person can easily escape the noise and commotion of the modern world.

Words by Joe Jacobs

Bea Apple never considered herself an active kid. And yet, when she and her family moved from the Bronx to Rogers, Arkansas, back in 1993, then 13-year-old Apple couldn’t help but feel the pull of the Ozark region. Its wide-open plateaus and deep, forested valleys, its sandstone bluffs cut by clear waters, begged to be roamed. The Natural State was green and vast—nothing like the home she had previously known.

Apple’s family had emigrated from South Korea to the United States in the ‘70s. When they first landed in Northwest Arkansas (NWA), they found community with a local Korean church. Apple’s first camping trips in the Ozarks were with that church group. They’d spend weekends at Hobbs State Park-Conservation Area and Beaver Lake, just outside of Rogers.

Back then, Hobbs had none of the modern, bike-optimized Monument Trails that Arkansas’ state parks have become known for today. There was no bike park in Apple’s hometown of Rogers, no trails tying Bentonville’s neighbors together with backyard ribbons of dirt. Prayers and poultry plants sustained life in much of the Ozarks. Throughout the ‘90s and early 2000s, NWA—a region centered around the cities of Bentonville, Fayetteville, Springdale, and Rogers— depended on manufacturing, transportation, and agriculture to keep the lights on. Mountain biking existed in the area, but only at the fringes. Tourism as a whole was still in its infancy. If there was one thing the region was known for, it was Walmart, which started as the Walton’s 5&10 (five-and-dime) in Bentonville, just seven miles northwest of Rogers.

Words by Jess Daddio

Before GPS devices, well-marked trail networks, and Google Maps, the paper map and word-of-mouth were the only navigation tools. Many available maps had limited information—some having had their last update around the time your dad drove that 1982 Datsun pickup out to see the sunset on some remote road.

During this era, mountain bikes consisted of rim brakes, 26-inch wheels, and a heavy steel frame with a rigid fork. Rear suspension may as well have been science fiction. Instead, sheer will and determination fueled riders eager to explore paths less trodden. These early mountain bikers rode to avoid pavement at all costs; this is the history of backcountry riding in the state of Arkansas, just as it was in most places across the United States.

In fact, backcountry mountain biking was part of the Arkansas riding scene long before the explosion of its self-proclaimed “Mountain Biking Capital of the World” trail hub in Bentonville.

Words by Matt Porter

The welcoming comfort of early autumn light livens the carefully puzzled sandstone slabs with a signature orange glow. It’s mid-September, and the first time in weeks that temperatures allow for any solid time on trail. Is that the sound of a hub or a cicada swarm? When conditions are ideal and mountain bikers emerge, it’s hard to tell the difference.

Summer resists quitting here in the central region of Arkansas. Every morning between June and September, riders check weather apps to see if the humidity level and temperature has dipped below 90% and 90 degrees. If so, it’s time to squeeze in a lap before work. If not, a ride after the sun retreats below the horizon may be more prudent. Arkansans live for the months between October and May—prime riding season.

Words by Liz Chrisman

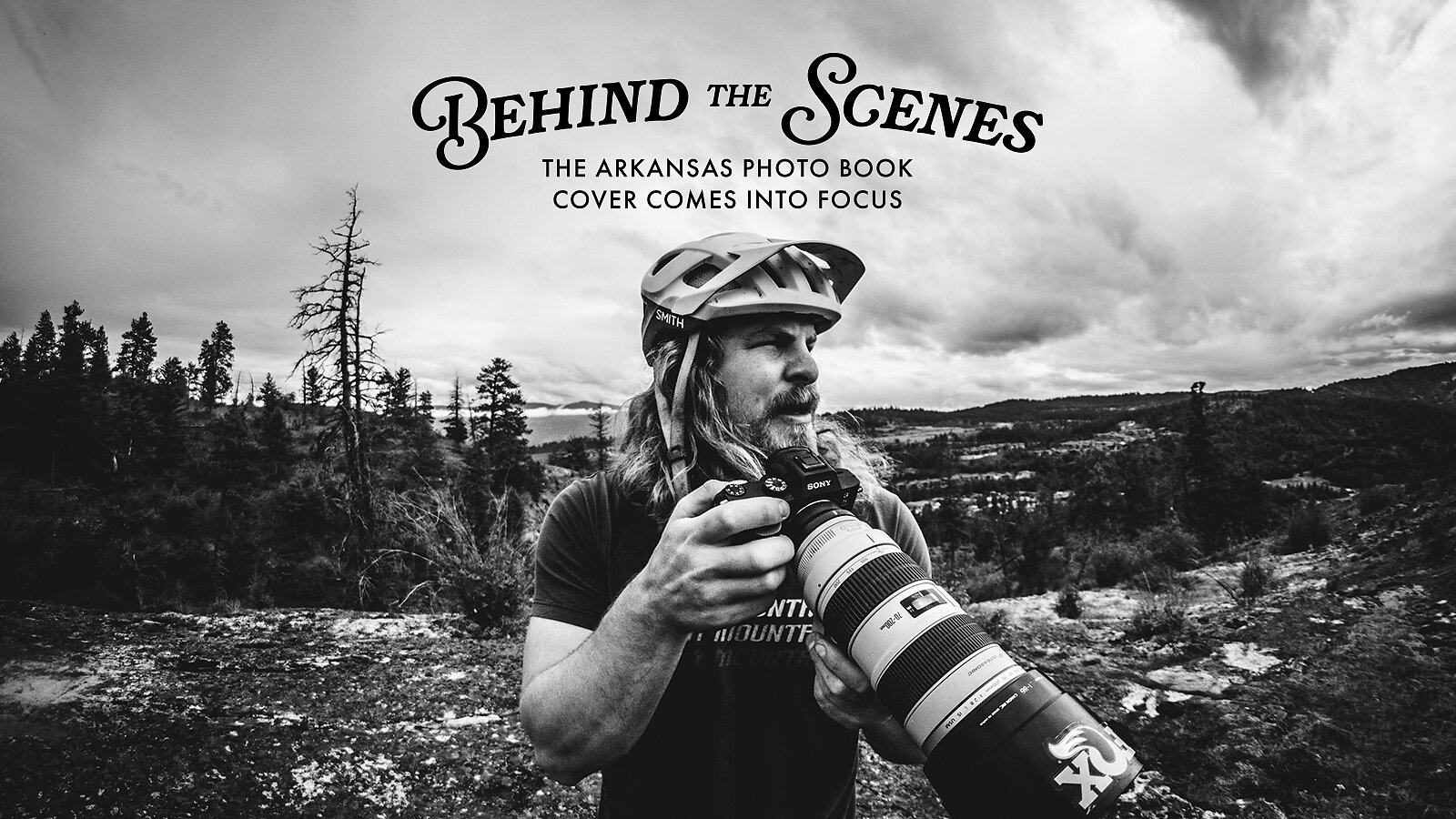

In early October 2023, Freehub senior photographer Riley Seebeck shuffled through his camera gear in the dark at the summit of Mount Nebo as he prepared for an early morning shoot with central Arkansas locals Jen Brazil, Johanna Flores, and Doug Housley.

Seebeck, a Wisconsin native who now resides in the Pacific Northwest, was on a 4-day assignment to document central Arkansas’ burgeoning trail scene. On the evening before his Nebo shoot at dawn, he scouted the location.

“I was just making sure that we’d all be in the right place at the right time. We made sure everyone was ready to go while it was still dark,” Seebeck said. “The longer I do this, the longer I realize I’m not just a photographer—I’m a manager, I’m a coach, I’m a director, all these different things.”

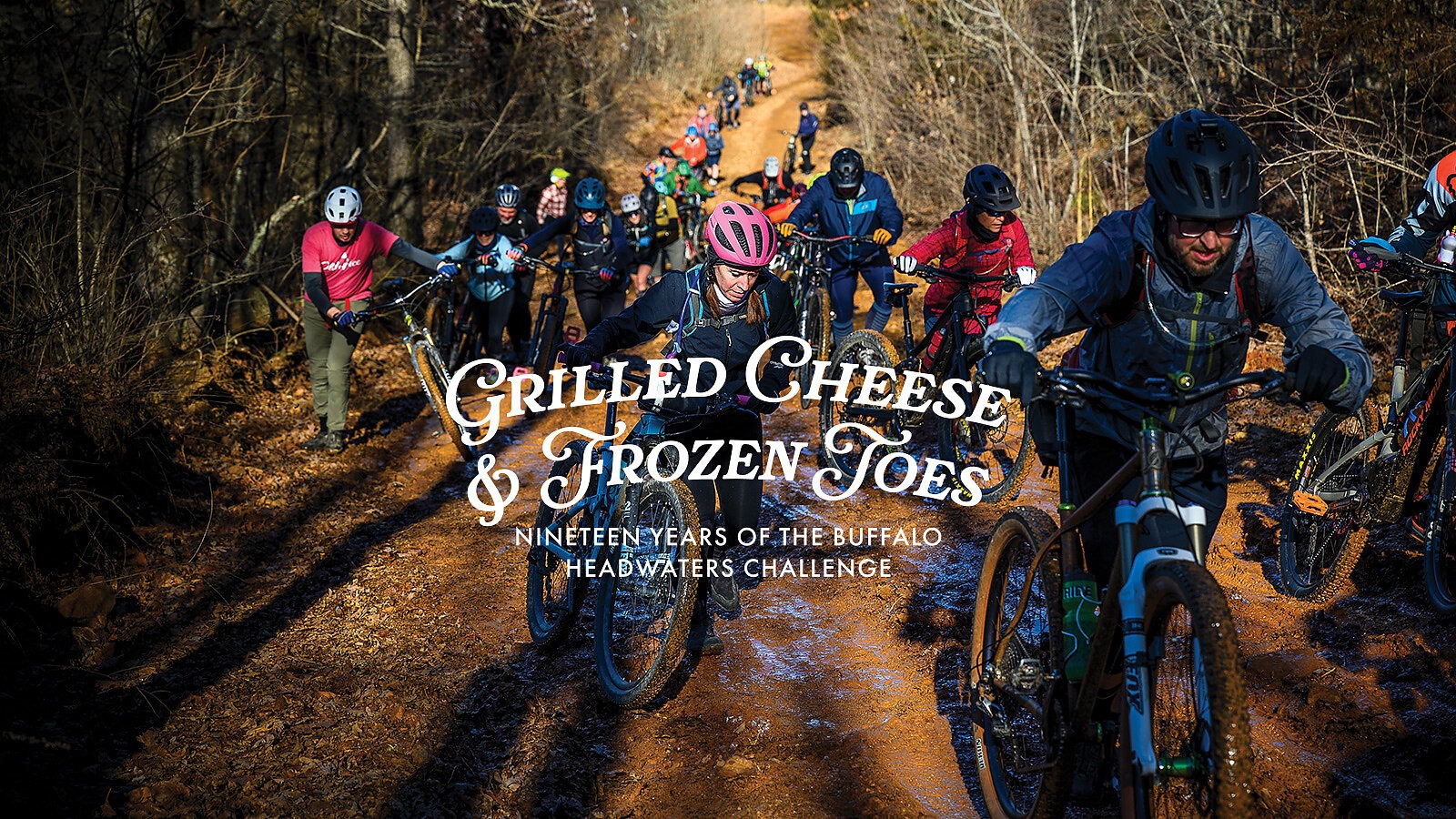

This February, the Ozark Off Road Cyclists (OORC) celebrated its 19th running of the Buffalo Headwaters Challenge, an annual bike bash based in Red Star, Arkansas, a rural community 50 miles southeast of Fayetteville in the Ozark National Forest.

Part party, part group ride, the Challenge is an intrinsic part of Northwest Arkansas’ mountain bike history. Long before the Walton family turned Bentonville into an urban bike playground, there were the Kuffs and the Whites, two back-to-the-land families who scratched singletrack into their backyards, then challenged their friends to ride from one homestead to the other.

Ira White was just a teenager when he first rode from the Kuff family’s homestead in the Upper Buffalo Headwaters to his family’s homestead one ridge south in the Big Piney Headwaters. Back then, in the early 2000s, the trails in the Upper Buffalo where Kate and How Kuff lived were more primitive than the Forest Service-recognized, International Mountain Bicycling Association (IMBA) Epic trail system that exists today. Some of the trails followed old logging roads and four-wheeler tracks that How and the White family had painstakingly cleared. Other trails were freshly benched. They were hand cut and narrow, steep and technical, but above all, they were remote.

Words by Jess Daddio