Island Life The Hawaiian Ways of Ohana, ’Ano and Ka Mahalo

Words and Photos by Riley Seebeck

My phone danced to life, casting a blue glow on the dreary Washington afternoon.

The text message was simple. Its insinuations were not. “December. Do you have any plans?”

The question came from my buddy Max Fierek, who was hunkered down in Minnesota for the winter. He had few riding options until the snow melted, so he’d conjured up a scheme to take us far away from the cold: a 10-day trip to the small Hawaiian island of Oahu.

Despite his current locale, Max knew Oahu well—he’d grown up there, spending 12 years of his youth on the island. Those childhood memories were to serve as our initial guide. Beyond that, we’d figure things out on our own.

It’s hard to imagine world-class trails existing in a culture built on surfing, but most tight-knit communities share similar values. In Hawaii, they’re called ohana (family), ka mahalo (respect) and ’ano (diversity), and they make for as well connected a mountain bike culture as they do a water one. I’d initially worried we’d find a heavy “locals only” attitude. Instead, we learned if you give respect, it will be readily reciprocated.

Our first experience with this came not long after we arrived, when mechanical troubles left us stranded and stumped. Pulling from his early Hawaiian years, Max called family friend and longtime local Steve Villager for help. Despite not having seen Max for years, Steve came to our aid without hesitation, showing up with tools, trail beta and good company.

Over the next few days, Steve would also serve as our guide to the island’s north side—particularly the Pupukea trail, part of Oahu’s largest trail system of the same name. It boasts both incredible jungle riding and unique history; the land was originally slated for a housing development after a Japanese developer imported nonnative tropical plants to start a greenhouse. The small community of Oahu opposed the idea, successfully petitioning against the development. The open space is now a federally protected state park.

It wasn’t long before Steve and other local riders swooped in, hand-building what would become the Pupukea trail network. The web is full of short climbs and exciting descents, through stands of apocalyptic-looking ironwood trees. The pine needles contain a bacterium that kills most vegetation on the ground, so it feels as if you’re riding through a rooty, tacky “dead zone” that is very much alive.

We followed Steve along the Pupukea grand tour, ending at cliff-top vista—or more accurately, Steve informed us, a turret-top vista, as the “cliff” was the roof of a WWII bunker. It was the huge ocean break below, however, that occupied our attention: Pipeline, the most famous surf spot in the world.

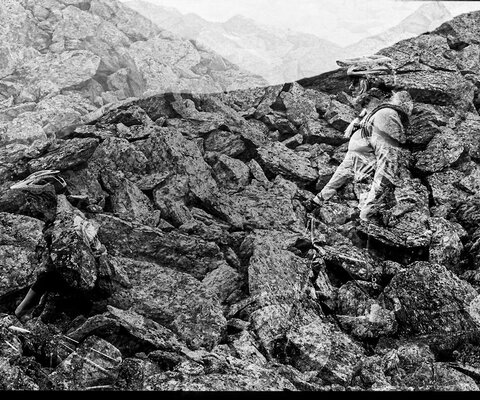

The next day our island tour moved eastward, where we connected with Mike Solis. Mike is founder of MTBHawaii. com, and few people are as tied into Oahu’s mountain bike community. It seems like Mike knows every rider on the island, every bit of history, and all the best trails, even if they’re not on his website. Oahu, Mike told us, has some of the best riding on all the islands, and he went about proving that with days of steep, rutted, needle-covered singletrack that dropped into tunnels of vibrant green jungle. We couldn’t stop laughing and high-fiving, even when we took “off days” to surf and enjoy the local cuisine. But a secret gem waited on the west side of the island. It was time to go.

Any passionate trail-builder knows the sense of ownership that comes with their creations, so Max and I were sympathetic when we got our first taste of the “locals only” attitude. We ran into Mark Pintaure at a sneaker trailhead for one of the aforementioned gems, who was understandably worried about tourists overrunning what he’d built. But that tension soon turned to conversation, and we learned about the incredible amount of sweat and blood Mark had put into these trails. For the previous five months, Mark had been getting up at about 4 a.m. and building until 10 a.m. to beat the heat. Over that time, he’d created huge 20-foot gap jumps, two-foot-tall pocket berms, and multiple wooden drops, all by himself and all by hand. It was an honor—and in line with the Hawaiian way we’d come to know—when he invited us to come see what he was so protective of.

After crushing a six-pack of ice cream sandwiches, on our last day Max and I met Mark in a random, wealthier-looking neighborhood. While we got ready, three more vehicles pulled up behind us, out of which spilled eight kids. They were all decked out in hand-me-down moto gear and full of questions, the youngest was Mark’s son, a 2-year-old who ripped on a strider bike. The posse of groms followed as we dropped into one of Mark’s creations, set on sessioning some of the different features. Within an hour, a crowd of parents, grandparents and siblings had all joined us on the trail, simply as spectators. I was awed by the display of community, and the support the kids receive to pursue what they love.

Almost as impressive was the existence of this trail system at all. Mark may consider it “secret,” but four vehicles parked in the affluent neighborhood above, and essentially an extended family in the woods below, is not exactly inconspicuous; in many places, it’s the type of situation that would lead to conflict. But it’s also one that captures those three key values of ohana, ’ano and, as Mark answers when I ask how so many entities can coexist, “Ka mahalo—mutual respect.”