Welcome to Issue 12.4

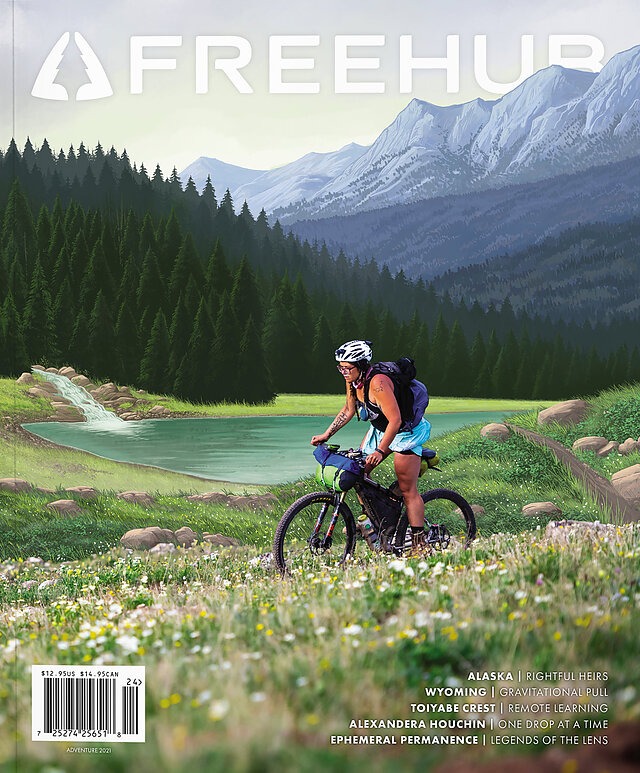

An unprecedented number of people are riding mountain bikes as an outlet for exercise and exploration and, as a result, discovering a truth we all eventually come to know: Every ride is an adventure. Freehub’s 12.4 edition is a celebration of this truth and a meditation on how adventure leads to discovery, both of the outside world and within oneself. In our cover story, ultra-endurance racer Alexandera Houchin writes about how her relationship with the bike has instilled a deeper understanding of her identity as a Native woman—and how she’s come to realize the act of racing is a ceremonial expression of her Ojibwe spirit. Transformative adventure pervades this book, with feature stories on a life-changing family bikepacking journey in the Alaskan wilderness and the existential reckonings of a rider attempting to clear a long-neglected trail in central Nevada’s remote Toiyabe Range. Welcome to Issue 12.4—a tribute to self-discovery and embracing the unknown.

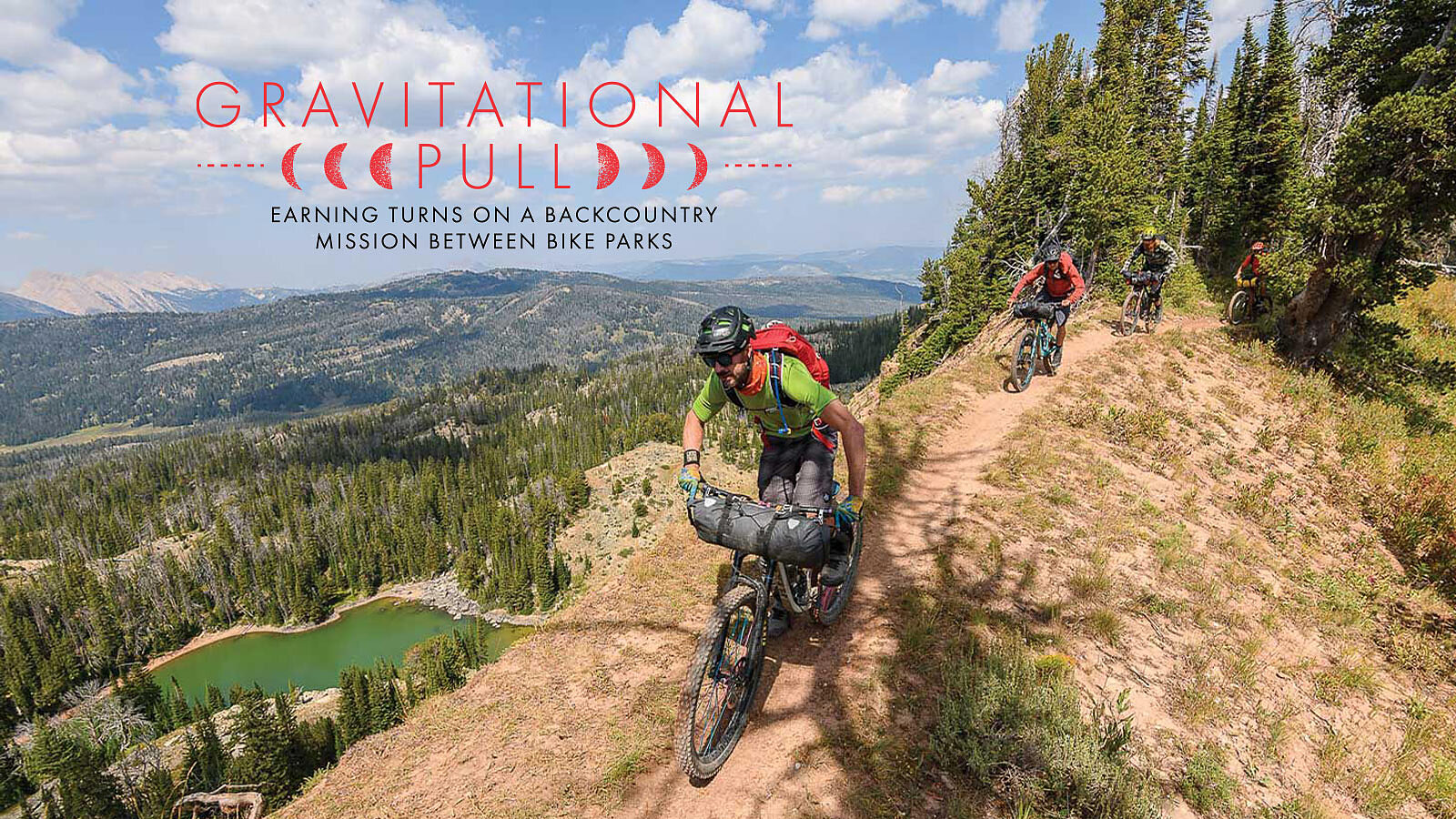

My invite came on a sweltering summer night as heavy smoke blanketed Colorado’s Front Range. The American West was on fire from the Pacific Coast to the Continental Divide and a grim haze filled the air. Casually glancing at my phone, I did a double take. Opening the message, I sensed an irreversible process had begun, like rockfall on a distant peak.

The invite from my good friend Chad Melis outlined a bikepacking adventure from Big Sky, Montana, to the Grand Targhee resort near the border of Idaho and Wyoming. A passion project for adventure photographer Fred Marmsater, our mission was to connect two bike parks with 260 miles of backcountry exploration—bikepacking bookended by trail smashing. Chad, a founder of REEB cycles, assured me it would be a legendary trip. “Fred doesn’t do anything halfway—I’m bringing my big bike.”

Excitement and doubt swirled through my mind. The route passed through rugged grizzly bear country and, adding to my concern, I wondered whether I could hang with a group of legitimate adventure professionals. I hesitated. Though, after months of COVID lockdowns, I felt a deep need for adventure. And with a surplus of vacation time, I had no excuse. I committed to the trip and immediately ran through my faithful gear checklist in a rush of ritualistic habit. My list is like an old family recipe, a time-honored formula for self-reliance.

Words by Steve Gardner | Photos by Fredrik Marmsater

I grew up knowing my mom was Native, but the fact that she was adopted out of our tribal community as a young child made my identity seem like a fantasy. The only Natives I ever saw growing up were on butter boxes, in cartoons (Pocahontas, Popeye and Peter Pan) and in history books, depicted eating supper with Pilgrims. Of course, I didn’t look like those Natives and neither did my family members. So, if we didn’t look Native, if I was estranged from my tribal community and if I couldn’t be understood by animals like I saw in the cartoons, it seemed as though I should let my Native identity dissipate. In mainstream society, there is little Indigenous visibility. In the cycling world, there is even less.

Despite this, I’ve carved out a home of sorts within the realm of ultra-racing, a niche discipline in which mountain bikers spend days—sometimes weeks—racing long distances without any outside assistance. The ultra-racing domain is populated by a small group of people, many of whom I’ve come to know. I hold the women’s singlespeed records for the 2,700-mile-long Tour Divide Race, the Colorado Trail Race (in both directions), as well as that of the Arizona Trail 300 race. For just about every big ultra-race, I scan the roster for familiar names and see friends listed, yet I rarely meet other Native people. In fact, I don’t think I’ve ever met another Native at a starting line. Deep in my spirit, I envision a world in which more Natives lined up to race but I’m not sure how to make that dream a reality.

Words by Alexandera Houchin

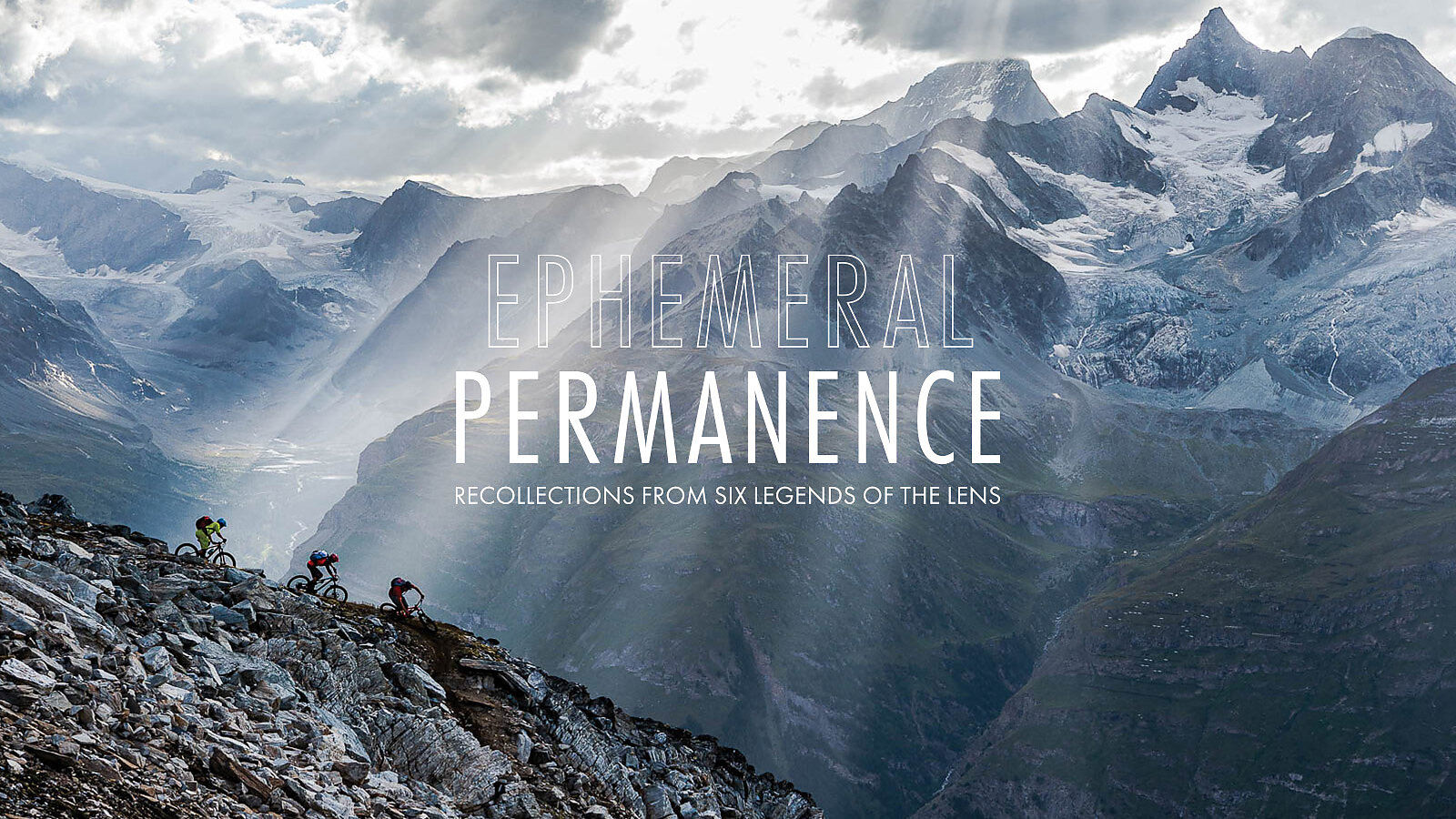

We live during a time when the natural world is changing more quickly than ever before. Ever-shifting weather patterns are toppling the paradigms of predictable climates, and regions we once viewed as being stable over the course of a human life are becoming volatile before our very eyes. Perhaps now more than ever, humanity’s relationship with the Earth—particularly its wild places—should be cherished in every moment.

We mountain bikers occupy a peculiar space on our planet, constantly striving to balance a delicate symbiosis between us and the dirt in which we play, and from whence we emanate. Mountain bike photographers, especially those with a proclivity for remote-ness, possess an intuitive understanding of the ephemeral essence of our flirtatious interplay with landscapes. We are but fleeting blips in an ageless continuum that envelops and embraces us, if only for a few seconds, as we marvel over the majesty of it all.

Photos and Words by Mattias Fredriksson, Colin Meagher, Dan Milner, Bruno Long, Margus Riga & Joey Schusler

It’s 9 o’clock at night, the temperature is 45 degrees Fahrenheit, and, still, there is plenty of light outside. It’s not exactly raining, but we’re huddled in the mist and the dampness is starting to settle in with a decisiveness. We’re starting to get cold in our riding gear and there’s still a laundry list of things to do before we can sink into warm sleeping bags.

Compounding our concerns, the last people we encountered on the trail mentioned that they saw a grizzly bear just down the hill from where we’re planning to camp. This should be par for the course, as we’re on a two-night bikepacking trip in the Alaskan wilderness. But this is far from any ordinary bikepacking trip, as it is the first self-supported bike adventure I’ve done with my entire family. We’ve just climbed more than 1,500 vertical feet with fully loaded mountain bikes, and it is way past our usual dinner time. The hunger and cold are taking their toll, and I know my family has a tendency toward “hanger” when deprived of food. Emotions are running high.

Words by Eric Porter | Photos by Justin Olsen

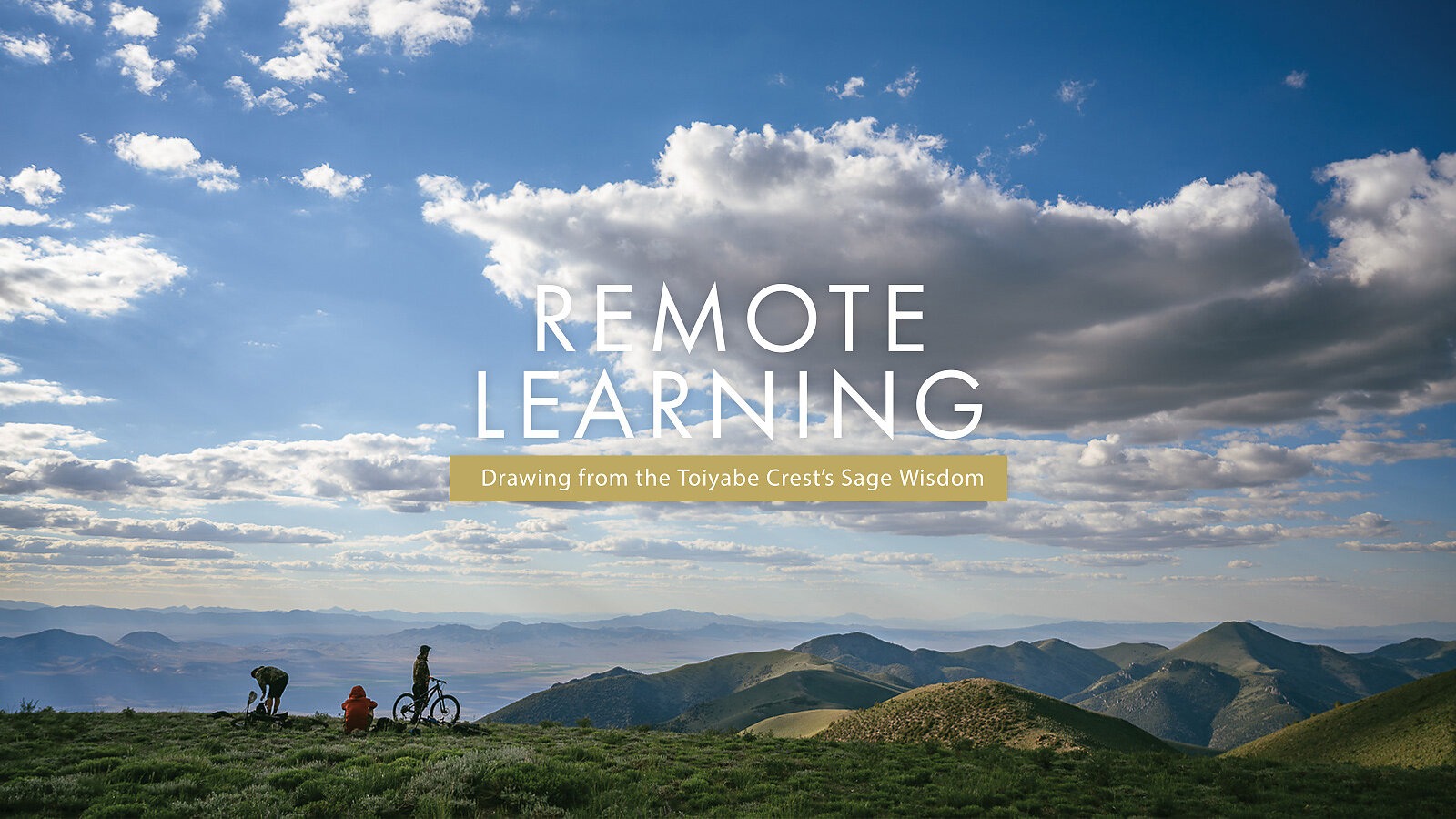

A short, stocky Latino man flashed a smile at me from under his wide-brimmed hat, moving his hands back and forth along a narrow ribbon of dirt that had previously been hidden by a thick wall of sagebrush. I’d watched him approaching from a mile away, free hiking across a massive slope with a flock of sheep following, tailed by his trusty sheep dog.

“¡Aaah … camino!” he exclaimed as he strode along the newly liberated path.

“¡Si!” was all I could muster in response, beaming widely, proud of myself for knowing what the man said. It was the first word I had uttered to another human in four days, because he was the first human I’d seen in four days. I stepped to the side of the trail and waved him through a freshly cut path up to the top of the ridge, where his giant white tent was pitched at an elevation of about 10,000 feet above sea level.

“¡Gracias!” he said, vanishing back into the sage with his flock close behind.

Words by Kurt Gensheimer | Photos by Ken Etzel

There’s no question that we mountain bikers are going farther on our bikes than ever before. The advent of modern suspension technology, lightweight frames, dropper posts and reliable brakes and tires has made it easier for us to venture higher into the mountains and wander deeper into places once considered downright crazy to explore by bike.

At the same time, advancements in bike-bag design have made it possible to pack ultra-lightly, stuffing the bare essentials into waterproof seat and handlebar bags compact enough to allow for unmitigated singletrack shredding on a fully loaded mountain bike. This, along with continued refinements in backcountry expedition gear, makes surviving in abject wilderness all the easier and compels many of us to roam inhospitable environments with un-precedented confidence.

Words by Brice Minnigh | Illustration by Victor Brousseaud

I hated high school. Admittedly, I was a dork, but still, aren’t most kids at that age? On top of my dork-ness, I was also a late bloomer physically. I didn’t top out until my senior year—the last three months of it. Because of this, I grew up as the little guy and was often pushed around or made fun of for it.

When I was younger and the same size as everyone else, I was an all-star baseball player. But once high school came, my growth stagnated like molasses in January. Meanwhile, my teammates were busy slugging home runs and discussing electric shavers. I got heckled off the baseball team—you can only be called “shorty” and “pipsqueak” so many times.

Words by Kurt Gensheimer

I used to work for wages as a tool under employer will. Eventually, choosing to shirk the restraints of debt, I sold my house and whatever other stuff people would buy to condense my life to the interior of a Sprinter van and the wide-open outdoors. My van is noticeable on purpose. I want to provide an example of getting something for yourself.

Since hitting the road in July 2008, I have ridden in 49 states—some 2,600 rides over 38,234 miles and counting. While I spend much of my time alone, my adventures teach me lessons about meeting others. Together, people make group decisions. Solo, I make my support group out of whomever else.

Words by Craig Bierly | Photos by Riley Seebeck

If you’re like me, you’re deeply captivated by mountain biking. Joking with friends, in a cheeky and biased way, I routinely assert that mountain biking is “the best sport.” But it can be hard to know what draws us so intensely to this curious activity.

Of course, there are the usual reasons, all of which have the merit of being true—mountain biking is fun and social, it’s great exercise and it’s an adventurous escape from the grueling rat race and absurdities of modern life. To some, these truths go so far as to provide a buffer from mental health issues. We know mountain biking enriches life, but for what reason do we, ride after ride, continue to come back and pedal our faithful machines? A deeper truth about our sport is fundamental to understanding what makes many of us tick—the process of overcoming.

Words and Illustrations by Brandon Kornelson