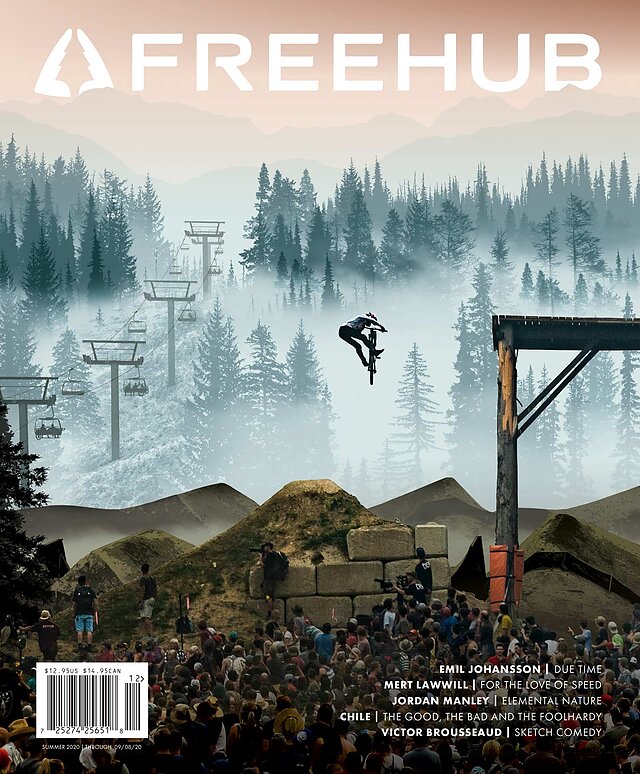

Welcome to Issue 11.2

Moving forward is an intrinsic characteristic of mountain biking. This is evident in the physical activity, but just as true in every other realm. Sometimes this progression is tangible, like the first iterations of suspension bikes designed by motorcycle legend Mert Lawwill. Other times, it’s psychological, felt while grappling with the harsh conditions of the Chilean Andes, or, for slopestyle star Emil Johansson, a near-catastrophic storm within the body. French illustrator Victor Brousseaud has found his own niche in creativity and comedy, a largely unexplored nexus within our culture. As it is often said, constraints are the catalysts for innovation—and our sport is absolute proof of this concept.

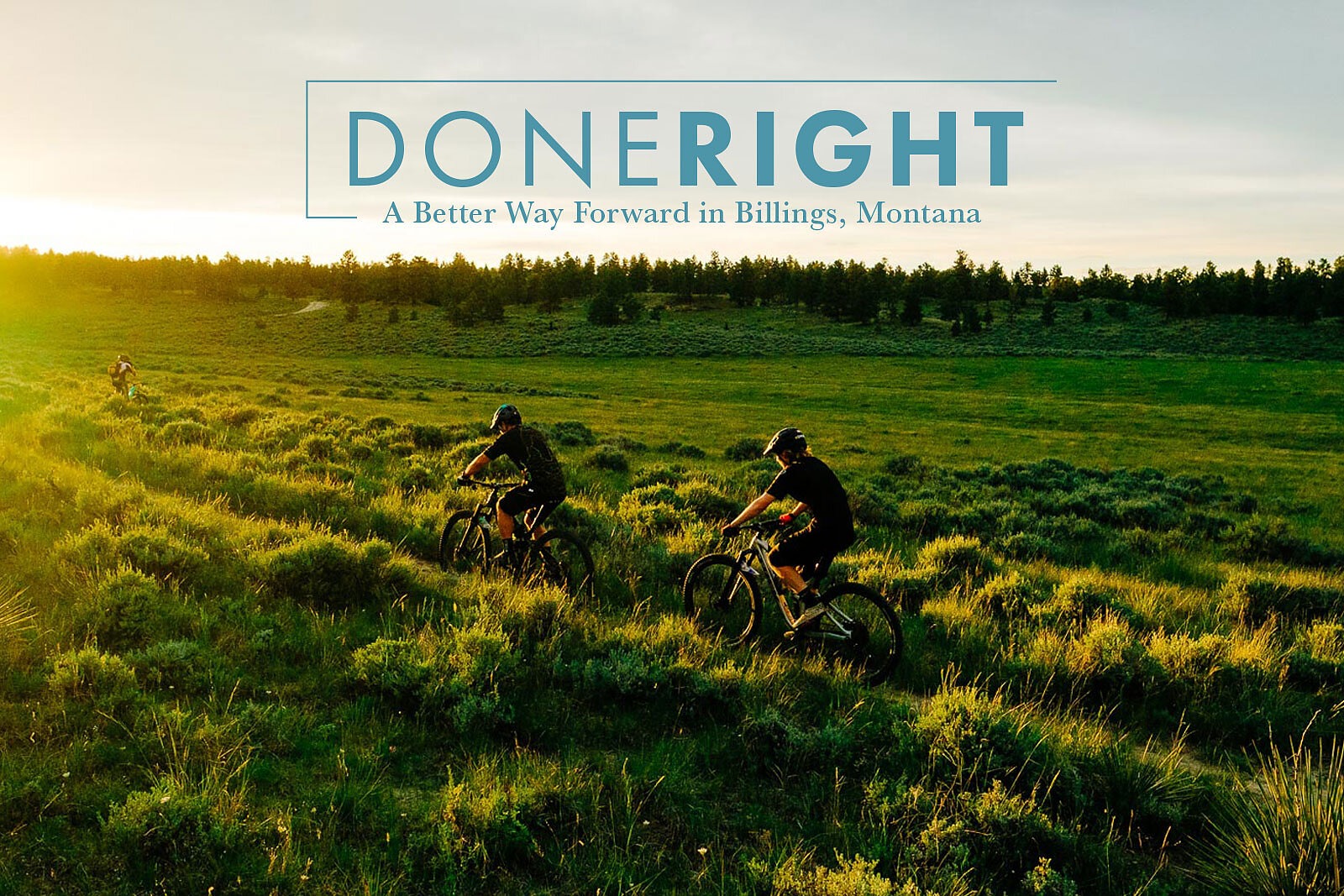

In southeastern Montana, things have a way of springing up overnight.

Billings, the state’s largest city, earned the nickname “Magic City” for the speed at which it seeded itself around the Northern Pacific Depot in the early 20th century. Like many stories out here, this one begins with a group of hardy souls scratching something new out of an unforgiving landscape. And like many stories of community trail systems, it nearly ends when land managers bust the builders of unsanctioned trails.

A decade ago, a group of guerrilla builders discovered the Acton Recreation Area about 18 miles north of town. With their eyes set on freeride lines on the rimrock and pine woodland, they began building gap jumps and sketchy wooden ramps on the cattle trails that wound through the 3,800-acre area.

“There were these massive, steep, huck-yourself lines out there—the kind where you hope you land in the right spot and roll away from it,” local rider Mckay Martwig says.

It wasn’t long before the Bureau of Land Management, which oversees the recreation area, caught wind of the illegal features. Tim Finger, the recreation manager at the time, confronted the “trail bandits,” as they came to be known. But this is where the story diverges from most...

Words and Photos by Aaron Theisen

Imagine yourself transported back in time to the year 1966.

You wander into the Bag O’Nails club in Soho, London, where some of the most important pioneers of rock ’n’ roll guitar hang out and play. When a tall, left-handed guitarist from Seattle takes the stage, the assemblage of musical icons—people with names such as Clapton, Lennon, McCartney, Beck, Townshend, Jones and Jagger—are stunned by what they witness.

Beyond his hypnotic stage presence, Jimi Hendrix blew everyone’s minds with his ability to make an electric guitar manifest the creativity bubbling inside him into something tangible. The notion of an artist using their instrument as an extension of their own body has become almost clichéd, but in Jimi’s case it was completely true. In Jimi’s case it was as if the guitar translated the brilliance of his soul into a language the rest of the world could also experience.

Fast-forward 50 years to the 2016 Red Bull Joyride contest at Crankworx in Whistler, British Columbia, where the most influential slopestyle athletes in mountain biking were gathered for their annual redefi nition of progression. When a tall, fresh-faced 17-year-old from Trollhättan, Sweden, dropped in, all of the sport’s heroes stopped to pay attention...

Words by Joe Parkin

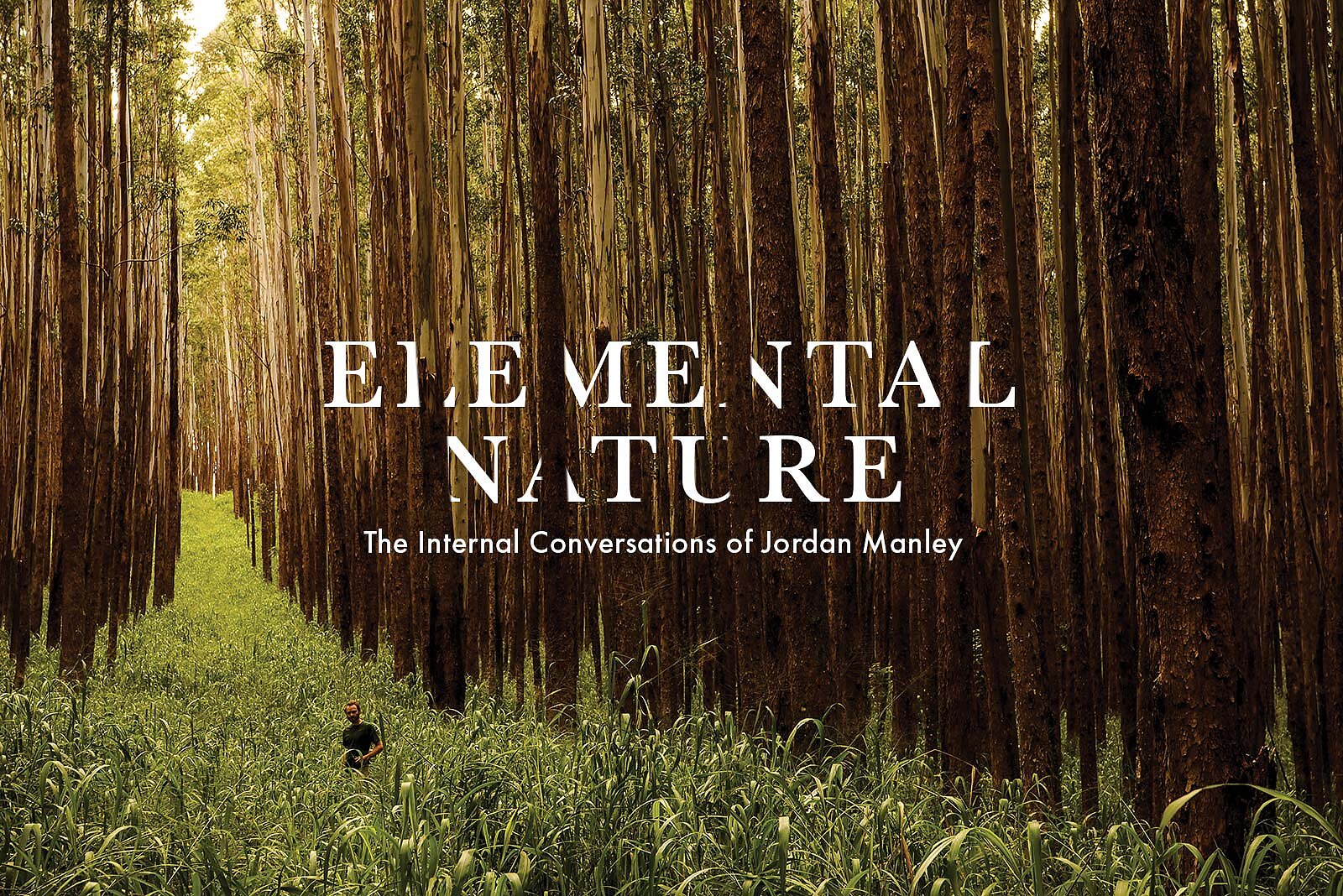

The first and last occasions on which I spent extended time with photographer and filmmaker Jordan Manley were far from ordinary circumstances.

The first was late in the evening at a hostel in Beijing. After a long flight from Vancouver, British Columbia, followed by a confusing navigation of the Chinese capital’s crisscrossing maze of subway tunnels and alleys, I walked blearyeyed into the dimly lit hostel foyer to see Jordan with his two main travel companions, professional freeskiers Chad Sayers and Forrest Coots. We were about to begin what turned out to be the most diffi cult, travel-intensive project of our careers.

Fast-forward a few years and Jordan and I were together again, driving back from the Great Basin National Park in Nevada so I could drop him off at the Los Angeles International Airport. In the course of the ninehour drive, Jordan didn’t say a word, other than to ask me to pull over so he could throw up. We didn’t talk on that drive, and after three months of traveling between British Columbia, Japan and Nevada together for our Treeline film, I pulled up to the lobby of the cheap airport motel where he was spending the night, took his bags out, waved goodbye and got back in my car...

Words by Garrett Grove | Photos by Jordan Manley

Mert Lawwill never really rode mountain bikes.

Perhaps this is because he was more used to doing 100 miles per hour on his motorcycle while racing flat track—the literal and historic definition of “foot-out, flat-out.” When that’s normal, riding something with pedals instead of a motor could understandably be boring.

The man is a living legend when it comes to motorcycles. He was at the pinnacle of his career in the late 1960s and won the American Motorcyclist Association Grand National Championship in 1969. The following year, he filmed for Bruce Brown’s documentary On Any Sunday. When it debuted in 1971, Mert was catapulted from a god among men on the racetrack to an American icon on the silver screen, right next to Steve McQueen.

But throughout his illustrious racing career, Mert also experimented in the then-burgeoning world of mountain bikes. Not as a rider, although he’d occasionally point one down the hill, but as a frame designer and suspension engineer. He’s someone who can’t help but look at something and think about how it works—and how it could work better. He also happened to have unparalleled knowledge and experience in the realm where physics and two wheels collide...

Words by Jann Eberharter

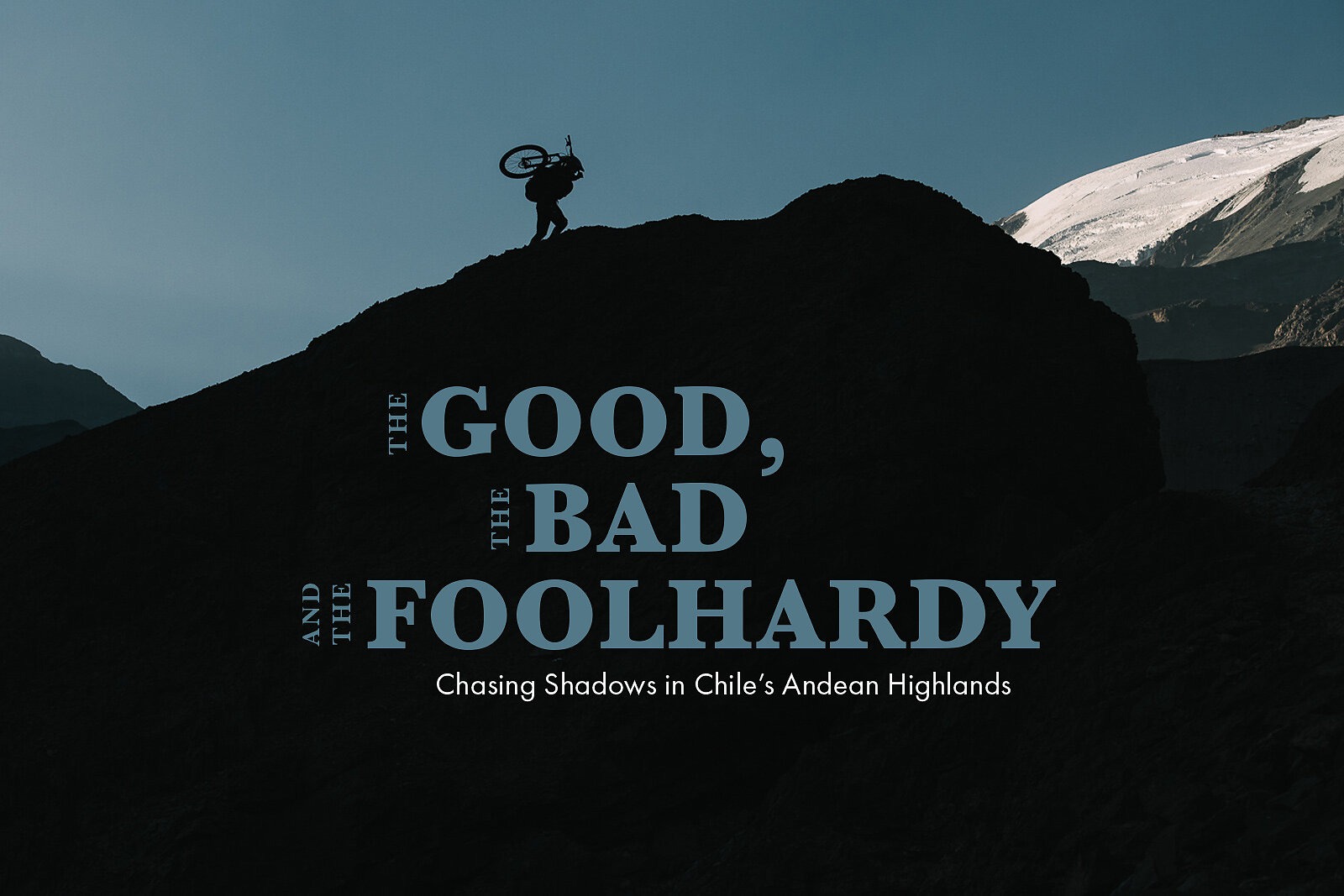

My eyes burned in the parching air as I squinted through blinding rays of midday sunlight at the imposing,

snowcapped anvil that loomed above the immediate horizon. I paused to catch my breath, fixating on the broad, flat summit of Cerro El Plomo, its alluring upper reaches girdled in the grasp of a sprawling glacier.

For a moment, the spectacular sight made me forget about the nagging headache I’d been trying to ignore for the last few hours as I steadily pushed my bike through the boulder-strewn barrenness of the Central Andean highlands. It was a blissful reprieve, but within seconds the steady pulse that was pounding against my helmet straps reminded me of just how quickly we’d been gaining elevation on our first full day at altitude.

“I think we’re gettin’ close to the base camp,” I said, turning toward filmmaker Spencer Johnson, who was lying on the trail below, his head propped on the bulging camera pack he’d been lugging all morning. “And it looks like it’s gonna flatten out after that next corner.”

“I don’t know if I’ve got it in me,” Spencer sullenly replied. “I’m feeling lightheaded, and I’m out of water.”

There was no need to push our luck. This was just the beginning of a weeklong exploratory bikepacking traverse through a rugged stretch of the Chilean Andes. Together with photographer Margus “Raptor” Riga and professional freerider Kenny Smith, we’d come in search of unridden chutes—and to document our latest escapade in the niche realm of backcountry freeride. As longtime friends and adventure buddies, we also hoped to show what can happen when the Raptor, Kenny and I—three thrill-seeking mountain goats with a combined maturity level of the average teenager—convene in a far-flung location to test ourselves in a largely unfamiliar environment...

Words by Brice Minnigh | Photos by Margus Riga

Being funny isn’t always easy. But drawing funny is downright difficult.

Combining humor and art walks a fi ne line in which both must be consistent and harmonious in visual and comedic style. So when it’s said that Victor Brousseaud draws funny, it’s a compliment.

Victor’s also had a lot of practice, which helps explain his honed style and ability to incorporate humor. As the product of an artistic household—his parents met at art school—drawing has been ingrained into the way he processes what’s around him.

“I saw [my parents] drawing when I was very young, and it was a normalinfl uence for me to draw,” says 31-year-old Victor. “When I was in the classroom, very young, I used to draw in the left margin of my books and the teachers were [criticizing] me for that. I can’t remember when I didn’t draw.”

The mustachioed French artist is a product and graphic designer by trade, working for Salomon skis, but he’s a mountain biker, BMXer, skier and surfer by life. He lives at the base of Mont Blanc, a short drive from Chamonix, France, the country’s mountain-sports capital. Growing up in the south of France, his dad was an avid mountain biker, though not in a style that appealed to Victor at the time...

Words by Jann Eberharter | Photos by Victor Brousseaud

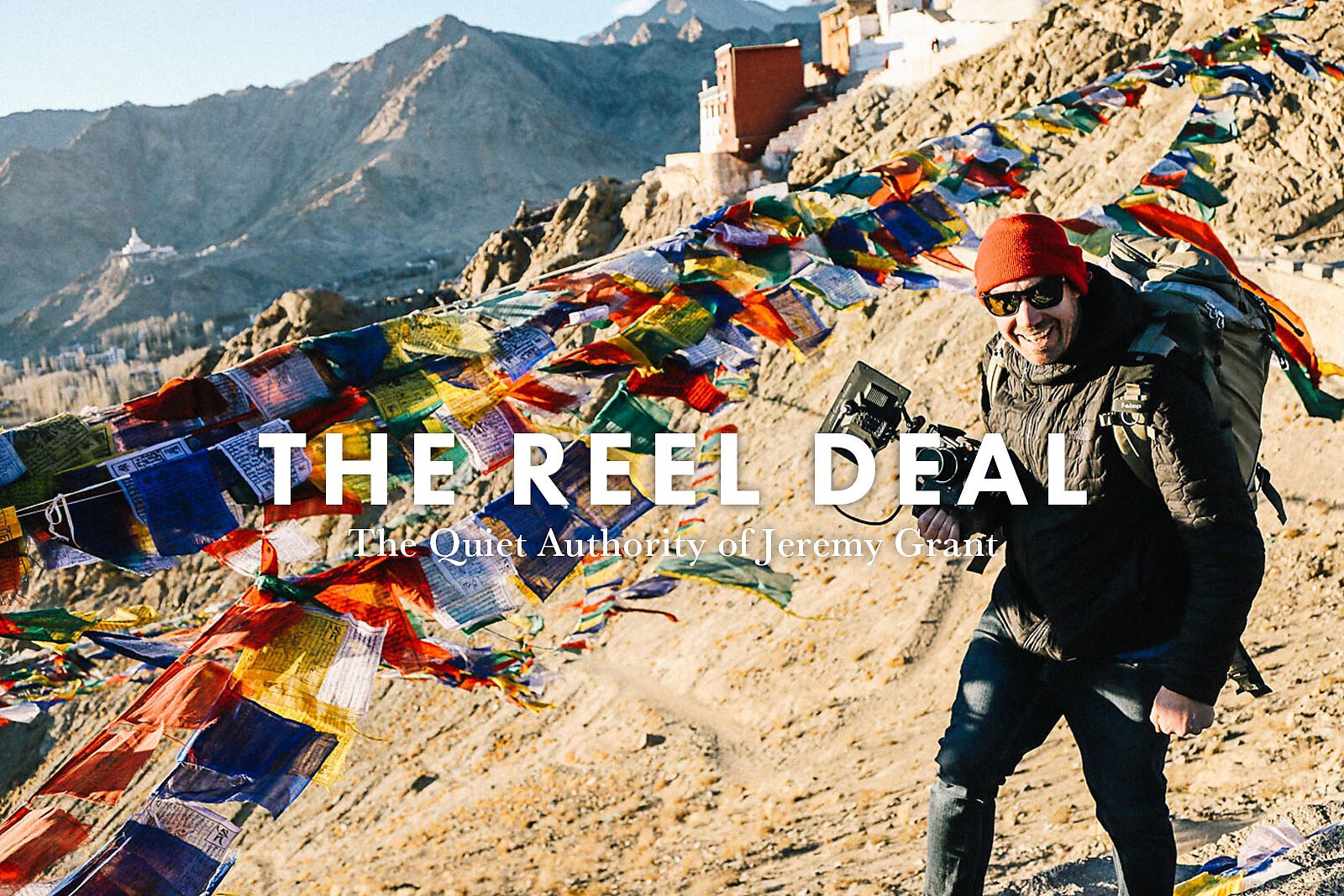

Daylight is fading as we pack up our gear from various ridges of a past Red Bull Rampage venue in Virgin, Utah.

Our crew has been here since 9 a.m. filming with Cameron and Tyler McCaul for Teton Gravity Research’s new film, Accomplice. Snow has been forecast, which means our filming window is about to close. Exhausted, we meander through the area’s signature red dirt toward the trucks below, with spicy margaritas and nachos on the brain.

Halfway down, director Jeremy Grant pauses with a tripod slung over his shoulder and takes in the view. Across from us is another orange-hued spine that winds down to the valley floor. Jumps and runouts spill over its ledges. Some are still rideable, while others need a bit of love. Cameron joins Grant and the two retrace old runs. They reminisce about unforgettable moments, like Cam Zink landing his legendary step-down backflip in 2013. Or Brandon Semenuk’s groundbreaking contest run in 2008, at only 17 years of age—which took him to the top of the podium and proved he was more than just a slopestyle kid.

During the last few months of working with Grant, I’ve come to appreciate these walks down memory lane. They’re impromptu mountain bike history lessons, especially when you consider Grant’s involvement with every Rampage since the event’s inception. He’s seen it all, only through a viewfinder. The list of influential athletes he’s filmed over the years is a veritable Who’s Who in the history of freeride mountain biking. But since he’s so easygoing and nonchalant, it makes it difficult to grasp what a badass he is...

Words by Katie Lozancich