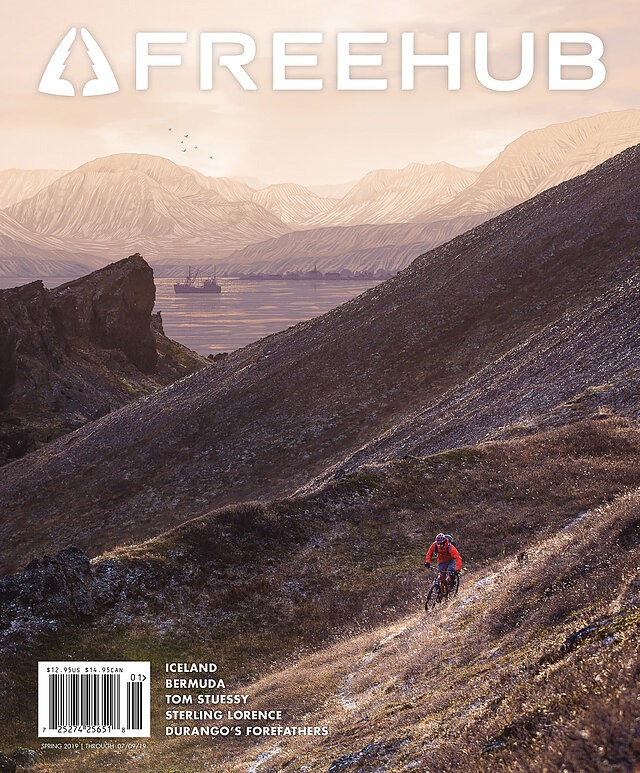

Welcome to Issue 10.1

Mountain bikers are a passionate bunch and their devotion to the sport comes in many forms. For photographer Sterling Lorence, it’s seen in his images, each one meticulously thought out, while the flourishing riding scene in Vermont is proof of Tom Stuessy’s dedication through advocacy. Other times, it’s small towns like Durango, CO that have supported mountain bikers since day one, or even entire islands, like Bermuda and Iceland, that welcome the sport with open arms. Issue 10.1 is dedicated to the purveyors of our sport.

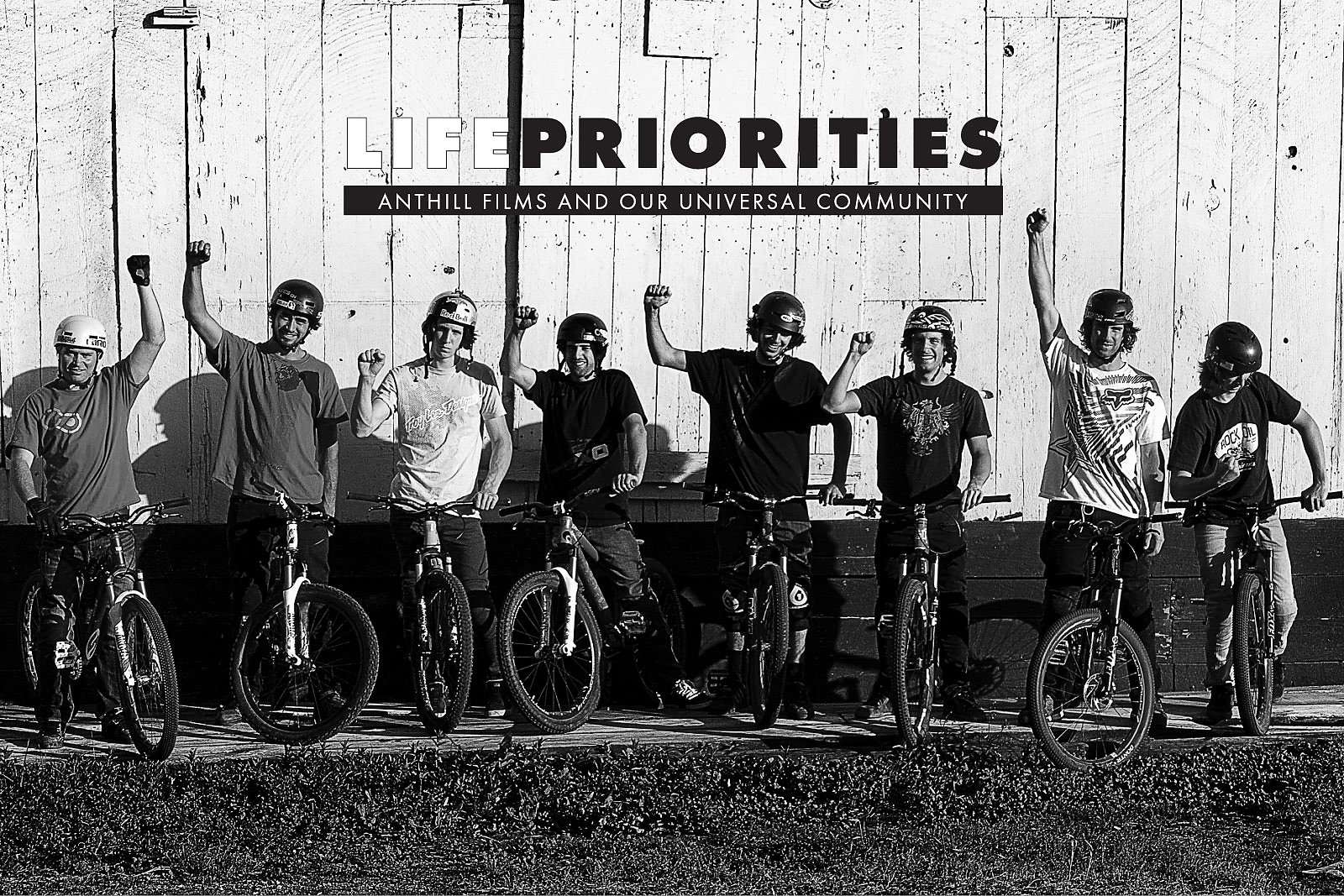

As auteurs of mountain bike motion pictures, Anthill Films has long heralded the role of community in the sport.

Local riders, clubs and trail builders have always been integral to the behind-the-lens logistics of any mountain bike movie set, providing crucial beta, pinpointing talent and offering support. Yet for the crew at Anthill, the community itself is more often than not also the inspiration for the story they wish to tell.

“That’s always been really important to us: Are the films and segments we’re making actually representing what mountain biking is, for as many people as possible?” Anthill Films Director Darcy Wittenburg says. “If you look at our films over time, for the most part, we’re trying to reflect the culture and community as much as we can.”

Capturing the nuances of mountain bike cultures— whether at local clubs in North America or in the world’s most far flung developing nations—requires extra manpower and equipment. In addition to filming the all-important athlete action, having an extra RED camera and operator on hand allows for more of the peripheral reactions and subtleties to find their way into the final edit. It’s that authenticity that often appeals most to the mountain bike public.

Words by Vince Shuley

By the summer of ’93, King was already older than all of us.

His years of working summer camps around Brevard, North Carolina hadn’t quite revealed his age yet, but everyone looked to him for direction. Most saw his athleticism on trails as an unwavering pursuit of adrenaline. But to him, the rowdy trails of Pisgah National Forest were an absolute source of anarchy.

We were poised on one of his days off at the start of Farlow Gap. The trail tumbled a couple thousand undulating feet through steep watersheds to an ancient trout-rearing station. Back then, the trail resembled a trail and not the tumbling, treacherous test piece that it is now. Even then, it was still the most difficult trail around.

“When you get to the crux, be sure to reef the bars real hard,” King said in his low drawl. He was so comfortable in the chaos he could coach the confidence to get you through anything.

“It’s all crux, King,” someone in the group called out. Nobody trusted V-brakes to control the freefall that was sure to ensue. Always the optimist, however, King howled his mentorship creed: “Follow my line and you’ll be fine!”

Back in the early 1990s, King rode those trails with what seemed like ESP. Many attributed this to his bike—his Pro- Flex 752 foretold what was to come, but his raw skill needed no technological crutches. By this point, King had already made ascents up Farlow on his futuristic rig—the descents were a given.

Words and Photo by Kristian Jackson

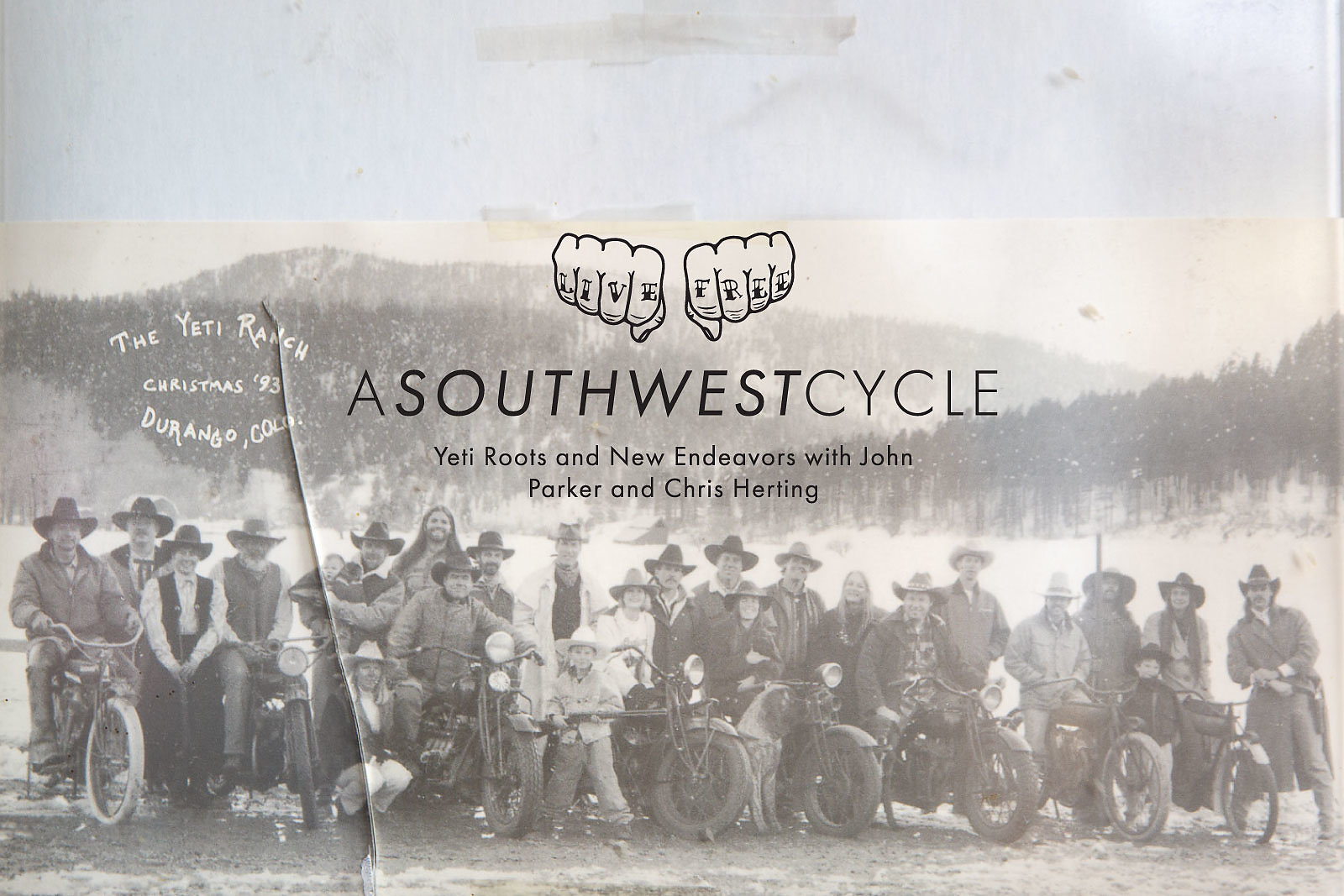

It’s a drizzly gray October morning in Durango, Colorado as I walk down the slick concrete sidewalk of Main Street.

From the looks of things, the area’s prized high-country riding season will now be abruptly cut short as the moisture pours out of the sky, piling high in the mountains.

I make my way into the Durango Diner, a greasy white-bread staple slipped into a sliver of downtown acreage. John Parker, a grandfather of mountain biking, wanted to meet here to tell his story. He’s easy to spot, a bear of a man with thick-rimmed glasses, knuckle tattoos and a flat-billed hat.

The diner is familiar ground for the 66-year-old Mountain Bike Hall of Fame inductee and warden of the sport. On the wall is a photo of one of his old Indian motorcycles—and one of him, actually, past the worn-out John Wayne painting and Native American art. The group photo he’s in reads “Yeti Ranch, Durango, Colorado, Christmas of ’93” and was shot in black and white, everyone dressed in cowboy attire, some on old bikes, some on old motorcycles, some standing.

Our meal is not of the quality he remembers, save for the green chile sauce. A lot has changed in Durango since its fat tired heyday in the late ’80s and early ’90s, a time when John and friends were running Yeti Cycles here. John is back, two decades later, with a new project called Underground Bikes. Within these foggy windows, over eggs and hashbrowns and watered-down coffee, Parker spills about mountain biking’s past and the path that’s led him back to the Southwest.

Words by Ben Gavelda

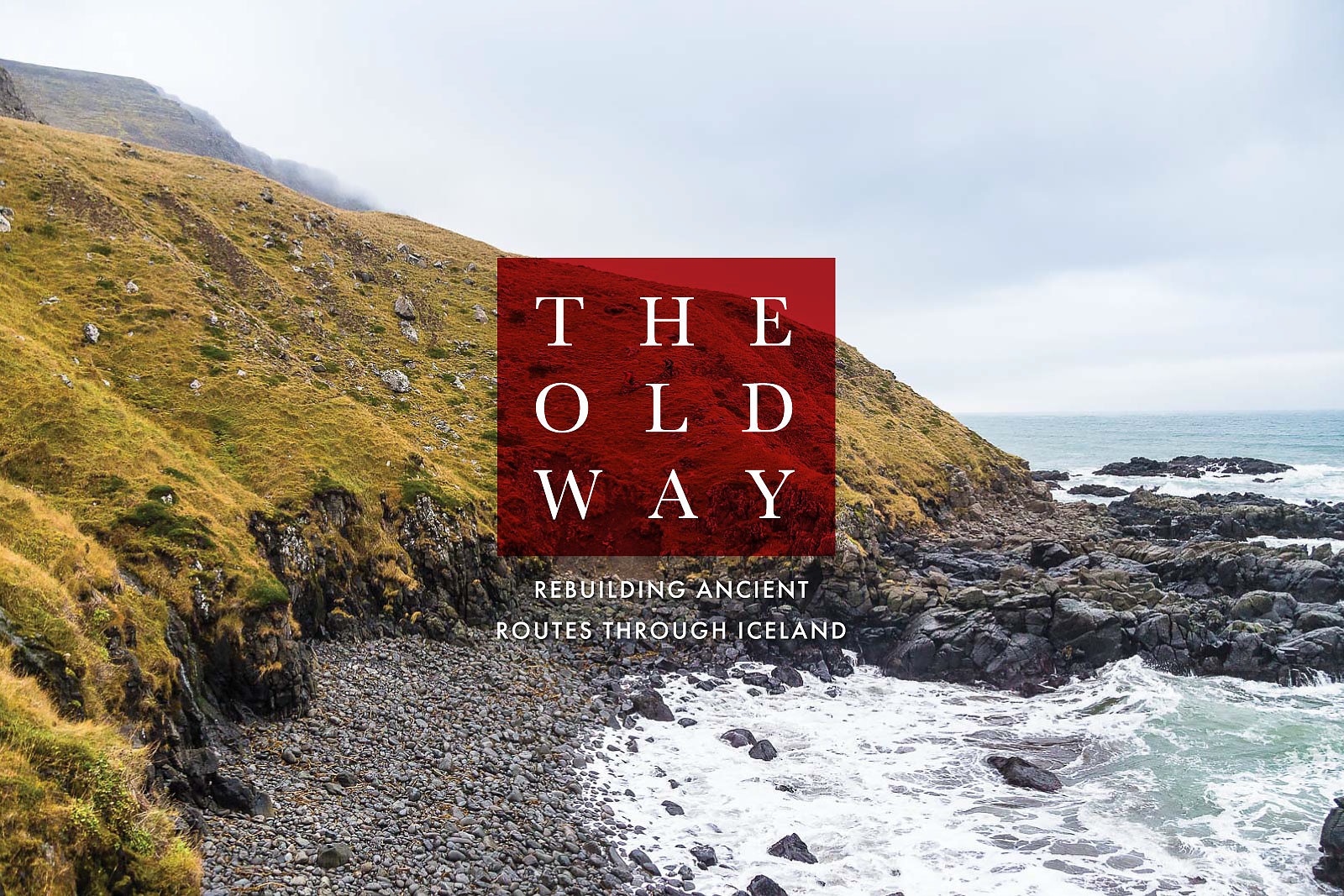

After a morning spent slamming my pedals into the muddy sides of our “trail,” repeatedly jerking to a stop mid-stroke, I’m beat.

These crisscrossing sheep paths looked so promising from a distance, but each trough formed by tiny hooves is just too narrow for a bike. Rain splatters against my glasses as I take a minute, lying on the spongy moss carpeting the valley floor and wishing a trail would magically appear and make this whole exploratory bike trip worth it.

Steely blue water foams against volcanic cliffs far below while a high plateau towers into the clouds above us, radiant with green lichen, tufts of golden grass and shiny blueberries. An early fall sunset glows through hazy fog, casting long shadows across the stark splendor of Iceland’s West Fjords. By all accounts, it’s beautiful. But a mountain biking destination? I’m not so sure.

Two days earlier, our 20-seater prop plane dipped beneath thick storm clouds, zooming toward basalt cliffs dropping 2,000 feet down to a dark indigo harbor bustling with activity. After the short flight from Reykjavik, the airplane banked a U-turn at the end of a narrow valley and we touched down on the single, questionably short, ocean-side runway of the Ísafjör∂ur airport, the largest town and hub of the remote, sparsely populated West Fjords region.

My friend Vidar Kristinsson met us at the baggage carousel with a huge smile. His looks identify him as a local—light oceanic eyes and a vibrant red beard, a modern-day Viking. “Welcome!” he said as he helped shuffle our baggage to the parking lot. After jamming three bike bags and gear into his Subaru, we piled in for the short drive to town.

Words and Photos by Mary McIntyre

You could suppose that photographers are artists at their soul.

That they’re master technicians, the camera a second extension of themselves. Or that they’re messiahs of light and how to capture it. And I could never answer those questions. I’m not a photographer. Just a friend. All I know is the story of how a kid who loved his backyard ended up creating a career whereby he could share it with the world.

The story starts some four decades ago. Sterling Lorence and I were lucky little buggers. His house was spectacularly positioned at the confl uence of a creek and the ocean. I lived just up the street. We were groms in paradise, and we knew it. We’d fish for fl ounders in our little dingies and have rock fi ghts on the beach. We lived on a circular road with little traffic and lots of kids, and from our earliest memories, we were riding bikes, exploring, and in the rare event we got bored, causing trouble. It was the late ’70s and early ’80s in West Vancouver, British Columbia, what is today one of the richest communities in Canada. Back then, though, it felt like we were living in the backwater.

I remember Sterl being especially drawn to Cypress Creek. He could practically see it from his bedroom window. The creek was an entity unto itself. In the winter it would pound with huge chocolate flow, full of debris and thunder. In the summer, a trickle of crystal clear mountain water. From Sterl’s house, when the water was low, we’d often clamber up the waterway. It would soon turn into narrow canyons and pools, then waterfalls and cliffs. Every year, as we grew older and braver, we’d venture farther up the creek, until we found ourselves in the heart of coastal old-growth forest. Trees hundreds of years old, draped with mosses and mist, under columns of rare light navigating its complex canopy, giant ferns and salal. Often, when the creek canyon became too steep and dangerous, we would clamber onto its upper banks. It’s here we found our first trails.

Words by Mitchell Scott | Photos by Sterling Lorence

Five or so hours into our ride for the day, one foot on the ground, arms draped on handlebars, I outwardly survey the lovely, colorful vistas stretched out below.

Somewhat less beautifully, I am dripping buckets of sweat, my quads protesting and heart pounding. Inwardly, I cannot fathom how I am getting my ass kicked. Again. I mean, for crying out loud, we are at sea level—practically riding inside an oxygen tank—on a tiny, flattish island in the North Atlantic called Bermuda.

Said vistas are barely 200 feet below us, where lush green slopes meet turquoise waters. We’d come to visit James Holloway, an avid biker with whom I’d made friends a couple years prior, and I’d been smugly considering coming back to the island for a bike race. I mean how hard could it be? So, James and the local crew undertook educating us about their cherished system, which, turns out, isn’t that mellow. Today, we are getting a tour of a few more of James’ favorite trails, followed by the promise of a beer ride, as James called it, in the evening with a few more of his mountain bike crew. I imagine a rolling, serene ride, caressed by tropical breezes and punctuated by refreshing beachside beverages. Beer ride reality, however, became much clearer by the end of the day.

The island’s trails are small, unique loops, and run the gamut from jungle terrain to spectacular windswept singletrack above oceanside cliffs. To get in a solid day of riding, you must continuously link up multiple trails, mostly in Bermuda’s national parks. Instead of being disruptive, it’s enormously entertaining, so much so that the miles pile up and you don’t even notice until suddenly your quads no longer respond properly.

Words by Brigid Mander | Photos by Liam Doran

When Tom Stuessy took the job as executive director of the Vermont Mountain Bike Association (VMBA), the organization’s bank account had only $3,800 in it.

The previous executive director had just moved to Arizona to work for IMBA, most trails weren’t mapped, clubs were competing for sponsors and a lot of the riding was a backyard rake-and-ride affair.

Stuessy inherited the awesomeness of the Vermont trail network, as well as the problems inherent in trails built primarily on private land. That small chunk of change could have funded a few batches of T-shirts or bought a decent collection of trailbuilding tools, but it wasn’t going to pay his salary or buy statewide insurance for clubs. To do that, Stuessy would have to reimagine how VMBA functioned.

Today, my house in Richmond, Vermont, has seven hours of singletrack behind it—all on private land— where I can ride my bike whenever I want. I refer to the network as “my trails,” but they aren’t private: They’re part of a mapped, multi-use network made possible by private landowners who’ve allowed the trails to exist. They’re built and maintained by volunteers. And there are about a thousand miles of these trails crosshatching Vermont. That’s a lot of singletrack in a state that’s 159 miles long and only 89 miles at its widest.

Landowners allow the trails to exist, volunteers build them, but it’s Tom Stuessy who really deserves credit for the health and growth of Vermont riding.

Words by Berne Broudy

The girls next to me are giggling.

Turning to find the source of their elation, I’m greeted by two big grins. Noticing my curiosity, one of the gals, who couldn’t be more than 16 years old, points to the line in front of her. It’s full of women with their mountain bikes, and it snakes out of view. “How could you not be excited looking at this?” she says. I laugh and nod in agreement, sharing her excitement. This is the sixth-annual Liv A-Line Women’s Only Session. The line probably would have been longer too, but Crankworx capped today’s attendees at 150 for safety reasons.

Pedaling toward the entrance of A-line in the mid-August heat, I pass mother-daughter duos, athletes, coaches, groups of friends and solitary riders along the way. Despite the reasons that brought them to Whistler, they’re contributing to a common goal: cultivating sisterhood within mountain biking.

Once given the cue, tey fly by, cheering as they go. Finding a break in the commotion, I sneak over to the first drop for a better angle to photograph. That jubilation dissipates with the next group that appears. Instead of gliding over the lip, they dismount and scrutinize the feature. With them is Lindsey Richter, a coach on hand for daunting features like these.

Richter has found that most of her students aren’t incapable of hitting these things. More often than not, the problem is they just don’t know how to approach it. She breaks down the technique and then rounds out the lesson by gracefully hitting it.

Words and Photos by Katie Lozancich

Subscribe in print

or online today to continue reading!

or online today to continue reading!