Russian Roulette Spinning Cylinders Around Europe's Mightiest Mountain

Words by Brice Minnigh | Photos by Dan Milner

Drenched to the bone and shivering, I fumbled through a tangle of underbrush and tall grass, straining to keep my bearings in the blackness of night.

Rain had been soaking me for hours, and with the mercury plummeting as quickly as my body temperature, there was no time to waste. We needed to get across a rapidly rising river before our bodies succumbed to hypothermia or sheer exhaustion. We also needed to find two teammates, who had apparently doubled back in search of a bridge we’d somehow bypassed.

This alpine thicket wasn’t making it easy. Nor was the fact that our only torch was on the head of my other teammate, Australian Dennis Beare, who was doing his best to light the way for both of us. I wrestled my bike through the dense foliage, chasing the sporadic light beams and stumbling in the shadows between them. With such fleeting visibility, I’d already rolled both of my ankles on the uneven ground. My irritation was mounting.

“Where the hell did Dan and Fred go?” I asked Beare as we peered through the darkness for flashes from the headlamp they were sharing. “The last thing we need right now is to be separated.”

“True,” Beare mumbled. “And I thought our first day was supposed to be the easiest one.”

His comment hung in the air like the moody clouds that had followed us for most of the day. Beare was right: We were barely 13 hours into what we hoped would be a world-first mountain bike circumnavigation of southwestern Russia’s Mount Elbrus, and we’d already run the gamut of hardships. The climb up Elbrus’ boulder-filled flank had been far more brutal than expected, with lung-busting hike-a-bikes up a seemingly endless succession of scree slopes. What we’d estimated would be 4,000 feet of elevation gain had turned out to be more than 6,000 feet. The descent from our first major pass demanded more mountaineering skills than actual bike-handling prowess. By the time we’d crept down the near-vertical drops at the bottom, we were out of daylight—and the rain had returned with a vengeance. Then we’d spent the past couple of hours wandering blindly back and forth along a boggy riverbank in search of the elusive bridge that would lead to a sheltered place to camp.

“This is seriously like looking for a needle in a haystack,” I exclaimed.

Just as the words left my mouth, a light flickered from the hill above us. Beare and I scrambled up to the source and were met by team mate Fred Horny, the French adventure rider who had inadvertently ditched us in desperate pursuit of the bridge. He pointed his headlamp at the river, illuminating a suspended bundle of logs, our primitive portal to safety. Waiting on the other side was Svetlana Kouznetsova, the Russian operator we’d hired to help transport our camping supplies to designated waypoints along the route.

“Pacheemoo vwee tak dolga yehalee?” she asked me, visibly confused as to why it had taken us so long to get there.

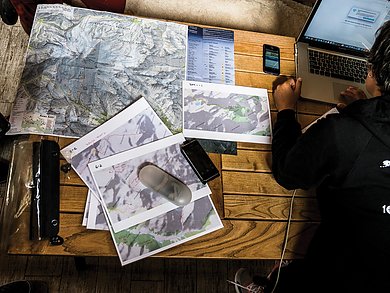

It was a valid question, but I didn’t have an easy answer. We’d planned our circuit along a loose string of trekking paths, but even cross-referencing online satellite plots with topographic maps can be an imprecise art. Though contour lines are a good gauge of steepness and general elevation gain, such rocky, undulating terrain can confound even the most experienced map readers. Add the variable of carrying bikes into the equation and you’ve got some complex mathematics.

The most complicating factor, however, was our decision to use support to carry our overnight gear. While it certainly lightened the cumbersome loads of unsupported bikepacking, it also required us to descend deep into river valleys each night. This meant much bigger extremes of daily elevation gain and loss. Each day, we’d have to climb out of a canyon, traverse a series of passes, then drop into the heart of another hollow and ride out to flatter plains to meet the support vehicle—a fourwheel-drive, UAZ-452 passenger van known as a buhanka (bread loaf). If the adversity of our first day was any indication, this was going to be the consummate adventure.

We awoke the next morning to blue skies and the fresh perspective that only a sound sleep can bring. Eager to get a jump on the day—and hopefully to get our first glimpse of the mighty Elbrus—we choked down our bland Russian oatmeal and hit the trail. Within minutes, the pitch became so steep we were forced to return our bikes to their familiar resting places on our shoulders.

It was amusing to note that, over years of exploratory bikepacking experiences, each of us had developed his own bike-carrying technique. Pausing to compare methods, we agreed that the Frenchman had the most flamboyant style: bike upside-down, top tube inverted on shoulders, wheels pointed toward the sky. As he hightailed ahead of us, we debated whether his hike-a-biking flair was more efficient, or if he was just fitter than the rest of us.

With Horny setting such a blistering pace, we topped our first climb by midmorning. At 10,650 feet of elevation, the Kyrtykaush Pass offered clear views of the Greater Caucasus mountain range, the snowcapped stretch of tectonic uplift that constitutes an impenetrable border between Europe and Asia. Soaring above all else was Elbrus, the undisputed king of the Caucasus. The glaciated stratovolcano even looked like a king, with the dormant domes of its two summits jutting through a thin halo of clouds to form a sort of natural crown.

After yesterday’s rain-sodden misery, the weather seemed too good to be true. Ecstatic, we exchanged high-fives, marveling over how quickly our luck had changed.

After yesterday’s rain-sodden misery, the weather seemed too good to be true. Ecstatic, we exchanged high-fives, marveling over how quickly our luck had changed. No one was more excited than Dan Milner, the alpine-loving English photographer who’d easily convinced us to join him on this multiday test of mettle.

“Can you believe it?” Milner yelled, his voice spiraling into a piercing falsetto. “What a difference a day makes!”

As if to answer this proclamation, an angry storm front suddenly drifted over the horizon, followed by an ominous roll of thunder. We pulled on our rain shells and beat a hasty retreat down the trail, with Horny and Beare roosting loose rocks at every turn. Though highly technical, this strip of decomposed volcanic debris retained just enough flow to get us off the mountain before the clouds unleashed their fury.

The track wound seamlessly from gray detritus into a verdant valley, where a band of wild horses galloped in fright at the oncoming hum of our hubs. We descended to a river before cutting upward across a series of ridgelines that gradually led us around to Elbrus’ northern fringe. Here, a sprawling plateau rose gracefully to the snow line, marking the point where many climbers start their ascents of Elbrus’ 18,510-foot-high summit, the tallest in all of Europe. Elbrus’ height has made it one of the Seven Summits, a revered grouping of the highest peaks on each of the Earth’s seven continents. Some of the planet’s most accomplished mountaineers climb Elbrus as part of their Seven Summits achievement, staging their efforts from a small base camp of wooden buildings that we opportunistically used to get a few hours of sleep.

Before the sun had risen the next morning, we were already pedaling up a trail that skirted Elbrus’ northern reaches along the grassy Bechassyn Plateau. The horizontal rays of soft light refracted off a purple layer of clouds, bringing a warm, golden glow to the tall grass around us. Between pockets of wispy mist, the mountain’s majestic face came into view, mesmerizing us as we rode in respectful silence. This was a mountain biker’s meditation. It was the main reason we’d come here.

Our moment of reflection was short-lived. The plateau suddenly dipped into a narrow gorge bisected by a fast-flowing river. This stream had shown prominently on our map, so we wanted to tackle it early, before the day’s glacial melt had begun in earnest. It was swift and deep in spots, but we managed to cross it without using the rope we’d brought along for the worst-case scenario.

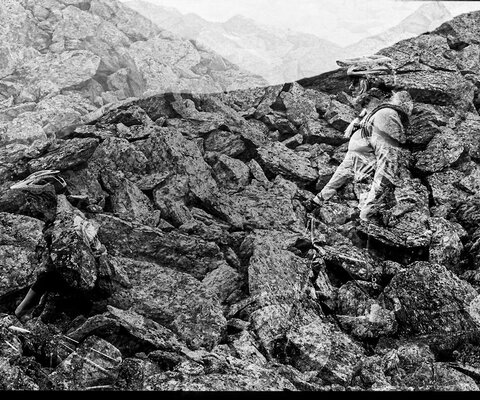

Keen to avoid more such rivers, we chose a higher route through a monstrous slate field that would lead to our tallest pass of the trip. The path was arduous, with big plates of ankle- grabbing shale, but it provided unobstructed views of Elbrus’ north face. Every aspect of the mountain was in high relief, from its towering massif to the yawning, three-pronged glacier that fed the rivers we’d mostly avoided. The glacier was both magnificent and menacing, the beauty of its blue ice contrasted by the haunting corduroy of countless crevasses.

It was no wonder this behemoth has captured human imagination since ancient times; even earning its place in the annals of Greek mythology as the site where Zeus chained the Titan Prometheus in punishment for stealing fire from the gods and sharing its power with mankind. In this sense, Elbrus itself was a god: a volcano of fire, granite and ice, ever-changing, yet with a millennia-spanning permanence that staggers human comprehension. I was humbled to be one of the humans fortunate enough to tread in its shadow.

But treading in Elbrus’ shadow takes a heavy toll—one that must be paid in sweat equity. The wasteland of pastel-hued stones we were schlepping through—remnants of molten pyroclasts spewed from the mountain’s fumarole more than 2,000 years ago —made for a slow climb. Navigating this labyrinth of geologic giants was tedious, every hard-fought step a strategic decision with immediate consequences. So, I turned it into a game: It was little me, a protoplasmic blip in the earth’s recent history, versus this army of post-Pleistocene goliaths. They mocked my foibles with their stony indifference, but to win all I needed to do was make it to the saddle far above.

With the dull weight of my 30-pound bike on my shoulders, it occurred to me that this would be all the more agonizing if we were carrying our food, fuel and camping gear with us during the day. I absolved myself of the puritanical guilt I’d felt about using the buhanka to portage our equipment. To hell with bikepacking purity; up here, the judge and jury were the elements themselves. And they were already a tough enough crowd.

Our support-vehicle decision was further vindicated as soon as we topped the 12,200-foot-high South Balkbashi Pass and surveyed our next descent—it was hideously steep and chunky. Freed from the fetters of heavy bike bags, however, we were able to ride it. Horny and Beare led the charge, straight-lining through burly rock gardens with speed and agility, all the way to our evening rendezvous point in a grassy meadow.

Buoyed by our progress, we set out the next morning in high spirits, shouldering our bikes and making short order of the long slog up to the 11,000-foot-high Koltsevoy Pass. Cresting the apex, we gazed across an expansive, barren plain, where an azure lake mirrored Elbrus’ snowy visage. It was tempting to linger, but the tightly spaced contours on our map had warned us that the descent ahead would be the mission’s most dangerous. Moreover, Kouznetsova had told us the buhanka was unlikely to make it to the meeting point we’d originally agreed. This would add several miles of riding to what we had first planned. There wasn’t a second to spare.

A few hundred feet into the downhill, our fears were confirmed: The map’s spiderweb of contours was, in reality, a precipitous chute filled with skull-sized stones. Worse yet, there was no runout, just a massive pile of boulders.

A few hundred feet into the downhill, our fears were confirmed: The map’s spiderweb of contours was, in reality, a precipitous chute filled with skull-sized stones. Worse yet, there was no runout, just a massive pile of boulders. With abrupt cliffs hemming us in, this was the only way down. A crash here could mean serious injury, even death.

“This is like Russian roulette,” I murmured. “And we’re spinning the cylinder.”

Horny, who revels in games of chance, plowed headlong into the funnel, setting off a mini rockslide that chased him all the way to the boulder heap. Once Horny was clear of the impact zone, Beare dropped in, further dredging the flume as he fishtailed to the bottom. Not being the gambling type, Milner and I opted to flounder down on foot.

Picking up the trail again, we cut a diagonal swath across several loose sections of sidehill before plunging into another shale-choked ravine that finally spit us out in a river basin. We needed to hug the stream to lower elevation, but the main track had been obscured by a maze of animal paths. Following these was a baffling business, leading from one dead end to another. A few hours of this maddening hopscotch and we finally reconnected with the primary artery.

The race was on, as we pinned it through rolling pastures and birch forests in a frantic search for the buhanka. Adding to the urgency, we’d entered the Karachay-Cherkessia region, a sensitive military zone bordering the Republic of Georgia. We’d obtained special permits allowing us to be here, so we were keeping a wary eye out for checkpoints.

Just as the sun slipped behind the mountains, we heard a whistle from across the river. It was Kouznetsova and Tambi Islam, the bread loaf’s proud driver, who motioned us toward a makeshift bridge downstream. We crossed it and rejoined the Russians, whose demeanors had transformed from doubt to downright jubilation. Kouznetsova rushed giddily down the bank, laughing and high-fiving each of us, while Islam’s ever-somber countenance had shifted to a broad smile. We’d turned the skeptics into believers, and they were clearly proud to be part of our effort.

“I didn’t know if this would actually be possible, but you guys are doing it!” Kouznetsova shouted in Russian.

As thrilled as we were to have found our camp before dark, a celebration was premature. Between us and the completion of our expedition lay the route’s second-highest pass, followed by the gigantic Azaubashi Glacier. These were formidable hurdles, and both had to be cleared in one day for us to reach our end point, the tiny ski town of Terskol. It was going to be a very long day.

We rose well before dawn and were already partway up the last major climb before the sun had risen over the snow-clad peaks above us. Much to our chagrin, the trail petered out into a confusing jumble of rubble that covered the entire mountainside. The only way forward was to find the path of least resistance. Once again, I turned it into a game, a geologic jigsaw that must be pieced together to complete the puzzle. My neck and shoulders ached under the weight of my bike, and my legs trembled as I teetered from one shifty rock to another. Near the top, the terrain became preposterously steep, and I struggled to maintain my footing as the shale shifted underneath me. We inched our way to the pinnacle, hooting in exhilaration at the 360-degree panorama the 11,650-foot-high Khotjutau Pass provided.

“Now all we have to do is get across that,” I said sarcastically, pointing to the sprawling sea of ice below. “There’re loads of crevasses, but at least we can see ’em.”

I’d been dreading this moment for days. Over years of near-fatal scrapes with polar crevasses, I’d come to view them as nature’s perfect coffins, silently waiting to preserve human bodies in a frozen state for the benefit of posterity. Just looking at this intimidating expanse of elephant-skin striations made me shudder. It was time for another round of roulette—and I felt like there were at least three bullets in the chamber.

We clambered to the glacier’s edge and stepped onto the crunchy upper layer of melting ice. There was traction, so we mounted our bikes and cautiously rode to the crevasse field. They were narrow enough to jump across. We spent the next few hours playing leapfrog over this succession of deep-blue slits, periodically forging foot-numbing streams and trudging through the brown sludge of moraines the ice pack had bulldozed into hillocks.

Lumbering down a muddy trench onto another tract of thick ice permeated by yet more crevasses, my heart began to pound. Some of the cracks were unnervingly wide, requiring a running start to clear them. At the far edge of the ice pack an alpine lake glimmered, revealing a nearby ribbon of singletrack leading out of the mountains. The stakes were high for these last several rounds, but I focused on the endgame, imagining the relief of the hammer striking an empty chamber.

One by one, we pulled the trigger, each time landing safely on the other side. As we neared the edge, the ice pack smoothed out, gradually tapering into the dirt. I turned for one last look at Elbrus, its emotionless, icebound summits indifferent to our very existence. We’d survived, but this mountain would long outlast us. I dropped the gun and pedaled humbly out of its shadow.