Origin Story Crested Butte and the Genesis of Singletrack

Words by Leilani Bruntz | Photos by Jesse Levine

Arriving in Crested Butte, Colorado is breathtaking. Expansive wildflower- filled meadows and a handful of meandering rivers serve as a buffer between the town and the towering, rocky peaks of the high horizon line nearby. As the sun sets over the plains of western Colorado, colossal mountains catch the last light of the day, turning their mineral-rich surfaces into fireworks of red and purple popping against the green and brown of the lower slopes. For five blocks, Elk Avenue serves as the town’s main social and commercial hub—the nucleus of a tiny cluster of charming homes.

Crested Butte is famous for its access to world-class mountain bike trails and its laid-back community of dyed-in-the-wool adventure athletes. Like the chicken and the egg, it’s impossible to know which came first. It’s logical to make the argument that the people created the trails. And it’s equally as rational to say that the trails have shaped the community. In reality, one couldn’t exist without the other. Each year, this becomes more evident.

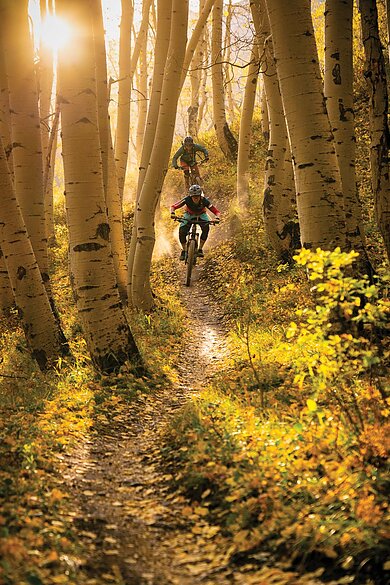

Today, it’s easy to see how Crested Butte fostered the genesis of mountain biking; the terrain offers something for everyone. Hundreds of miles of singletrack wind out of town and stretch into nearly every part of the Coal Creek watershed. There are close, easy loops for those new to fat tires or those hammering out a lap after serving tourists coffee all day. There are lift-assisted downhill trails that snake down nearby Mount Crested Butte. It’s easy to link trails into all-day rides, alpine epics, bike-to-peak-bagging adventures, and even multi-day bikepacking trips. The beauty of Crested Butte is that all of these can start at the coffee shop and end on the sunny banks of a vibrant watering hole.

Crested Butte authentically holds onto its historical roots as an old western mountain town. There’s a sense that the culture and the trails have always existed here. Both have been shaped by the people who call it home. The feeling of grinding up singletrack or floating through handlebar-high sunflowers and lupine is a process, not a product, and that process is storied. It begins with the invention of the mountain bike on the once-muddy dirt roads of town and a hardscrabble path that climbs up a high mountain pass.

Long before mountain biking even existed, Crested Butte was a winter paradise. During summer months, three roads lead into town. In winter, there is one. Each winter Crested Butte is nearly snowed in by an annual 190 inches of average snowfall, leaving the cold, quiet valley surrounded by pristine mountain slopes. In 1963, the opening of Crested Butte Mountain Resort’s first gondola attracted a first wave of “ski bums.” Crested Butte eventually became known more broadly as a ski town—a down-to-earth, hardcore one, that is, especially when compared to the glitz of Aspen on the other side of the mountains.

Longtime local and Mountain Bike Hall of Fame inductee, Don Cook, is one of the original visionaries who put Crested Butte on the map. The passion of Cook and his cohorts ignited the development of Crested Butte as a bastion of grassroots recreation. Their desire to share their new way of riding a bike was the impetus for gatherings, events and races—some of which still happen today.

Cook recalls visiting the valley to go spelunking up Cement Creek with a friend attending Western State University in Gunnison. Though the weather was awful, the place itself was captivating.

“The streets were all mud,” Cook said. “I could see the sleepy little ghost town was my style.”

The following year, in 1977, Cook got a lift operator job that bought him the ski bum life he always wanted.

“It was the first of everything. The first bike event, the first official mountain bike club, the first mountain bike trail development, and the first mountain bike destination.”

—Don Cook

“It just turned out to be so much fun, I stayed,” Cook said.

Those muddy streets remained unpaved and pothole-ridden until the summer of 1983, when true mountain biking in the area had taken off. The transplants that came to Crested Butte for this new era of mountain living rode bikes out of necessity. Instead of beating up their Ford pick-up trucks or small Honda Civics, they used “old, stripped down 1950s cruiser bikes as a way of getting around town,” Cook said. Affectionately known as “klunkers,” these cobbled-together bikes were the original mountain bikes.

As legend goes, marauders from Aspen rode their motorcycles over Pearl Pass and into Crested Butte to smoothtalk women at the Grubstake Bar. In retaliation, a group from Crested Butte who called themselves the Grubstake Gang decided to use their new klunker bikes to ride to Aspen for their own antics.

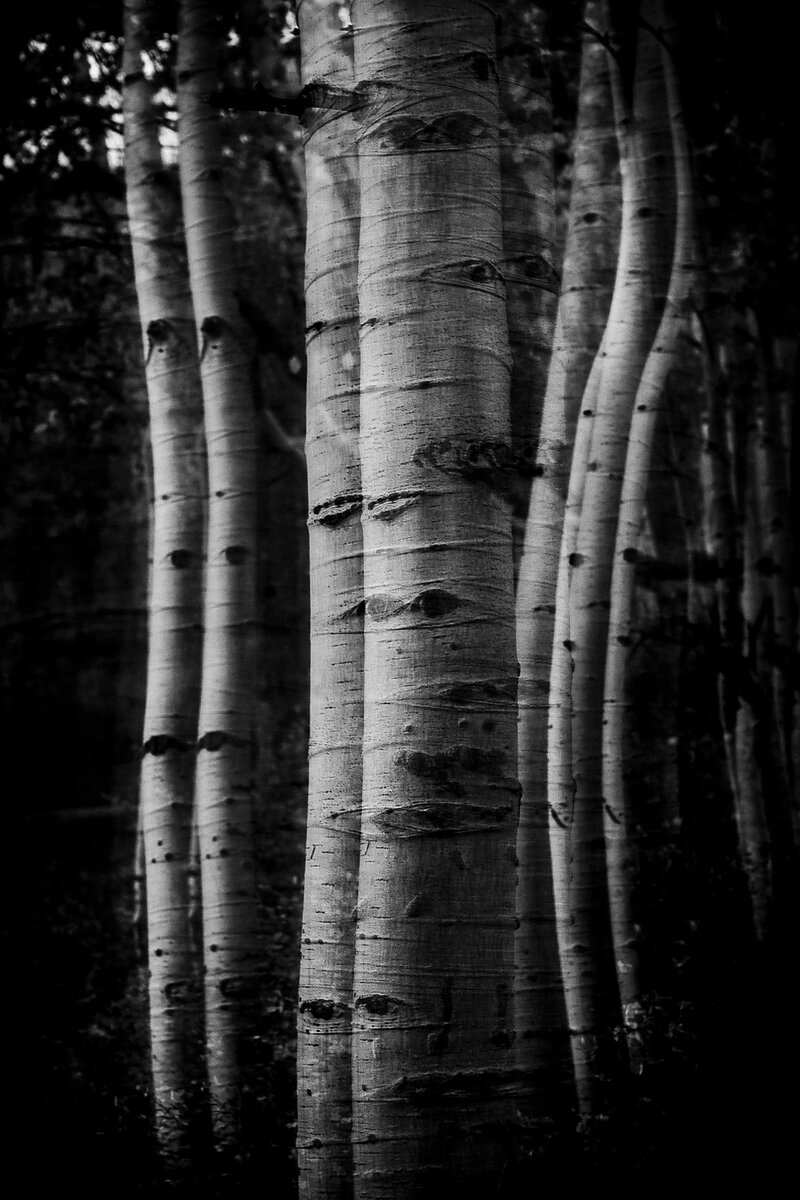

Pedaling and pushing their raggedy rigs through golden aspens in autumn 1976, they set out on klunkers to climb a rough, 27-mile road known as Pearl Pass. Originally a trade route between the mining towns of Aspen and Crested Butte, it’s a punishing passage comprised of doubletrack littered with loose rocks that meanders up increasingly harsh grades before finally topping out at 12,700 feet of elevation.

The group pedaled, pushed, then carried their bikes as far as possible. Alas, the bikes weren’t as tough as the riders—tires popped, hubs exploded and handlebars rattled out of their stems. Richard Ullery was the only one to make it up the pass that year. For the descent, hopping in the back of a truck was mandatory to prevent the bicycles from fully rattling apart and to preserve them for the 13 miles of pavement from Ashcroft into Aspen. Most of the crew returned to town in support vehicles with broken gear, beat-up bodies and tales that got better with each beer.

Meanwhile, another group of visionaries was making headway on mountain bike technology in Marin County, California. The story of riding over Pearl Pass reached these enterprising riders, and two years later, riders from Marin traveled to Crested Butte to experience the epic ride themselves. That first official tour brought together individuals who would soon transform the world of mountain biking such as Wende Cragg, a pioneering mountain bike documentarian; Charlie Kelly, founder and editor of the Fat Tire Flyer; Joe Breeze, credited with building some of the first mountain bike-specific frames; and Gary Fisher, who went on to found his namesake bike company.

Their stories spread like a wildfire. Within a few years, 300 people registered for what is now known as the first-ever mountain bike event, the Pearl Pass Tour.

“It was the first of everything,” Cook said. “The first bike event, the first official mountain bike club, the first mountain bike trail development, and the first mountain bike destination.”

Cyclists interested in offroad travel came from all over the country to ride Pearl Pass before celebrating together at a campout in Cumberland Basin. Word was out. Crested Butte was a mountain biker’s paradise. The Pearl Pass Tour morphed over the years to become Fat Tire Bike Week, a festival of wild times and guided rides.

Back then there were no trail signs, maps or little blue dots on a screen to help with navigation. In an era when almost every mountain bike ride carried an element of exploration, Fat Tire Bike Week gave visitors a rare chance to experience the area like a local. Group rides were guided by those who, in many cases, had uncovered the trail

being ridden.

One of these early explorers is mountain bike legend Dave Wiens. Wiens is best known for his six consecutive wins at the Leadville 100. Including a famous defeat of a turbo-charged Lance Armstrong who was left to choke on Wiens’ dust for the day. Wiens moved to Gunnison in 1986 to attend Western State University (WSU), but his real motivation was to live somewhere he could ski and kayak. Like most students drawn to WSU, the abundance of various mountain pursuits drew out the completion of his education.

Wiens still calls the valley home, but he was once a total newbie, pedaling a three-speed mountain bike in his jeans and kayak helmet. On a day of exploratory riding in 1987 he went hunting for the Deer Creek trail but missed a turn and ended up riding further into the valley. Looking for the inconspicuous correct path, he spent the rest of the day searching to no avail. The long summer day was coming to an end when he had a chance encounter.

“Here comes a guy on a mountain bike. And I look over, and there’s the trail,” Wiens said. The rider showed him the trail, a narrow path no more than an arm’s length wide, concealed by grass on either side.

Today, Deer Creek is an 11-mile trail connecting the townsite of Gothic to the Brush Creek drainage via a larger 29-mile loop that climbs more than 3,000 feet. It’s well known now, but not much easier. Locals refer to it as a ride that feels uphill both ways.

The extensive trail system that exists today weaves together the area’s heritage. Early mountain bikers found paths laid down by many generations of people who lived here before, beginning with the Ute Native Americans who followed game trails for hunting. In the 1870s, miners beat in paths while prospecting in the mineral-rich mountains. When cattle and sheep ranching replaced mining in the 1900s, the livestock created more trails as they grazed in the highlands during summer months. Eventually, those same trails were repurposed for riding klunkers. Many of these trails remain legendary such as the 401 and Teocalli Ridge.

Amid the fun and exploratory times, Crested Butte was unknowingly laying the foundation for more formal trailbuilding and mountain bike trail advocacy. Cook recognized a need to get organized, so, in 1983, he helped form what became the first mountain bike organization, the Crested Butte Mountain Bike Association (CBMBA).

Passionate and inspired to get involved, riders started building relationships with land managers, ranchers, and other stakeholders. Through the process of surveying and creating an inventory of existing trails they gained trust and eventually permission to host trail workdays and build sanctioned trails. Cook’s foresight earned bikers a seat at the table with partners such as the U.S. Forest Service that, for the first time, began including them in decisions regarding the 2 million acres of public land it manages in the valley.

Gunnison, which sits 27 miles down the valley from Crested Butte, is drier and more desert-like. It didn’t establish its nonprofit trail organization, Gunnison Trails, until 2006 when core riders such as Wiens decided to spearhead trail development specific to their part of the region. Now, with two well-established mountain bike organizations in the area, it’s common for locals to travel from one side of the valley travel to the other to ride and volunteer on trail days. Gunnison offers dry trails in the shoulder seasons while alpine terrain further up the valley remains buried under snow.

Cross-country races near Gunnison have thrust it into the limelight and helped evolve the high-alpine-desert-riding haven, Hartman Rocks. The network offers loops ranging from flowy, smooth trails through fragrant seas of sagebrush to more technical singletrack along rocky outcroppings. Optional lines allow riders to challenge themselves as much or as little as they like and progress safely.

Mountain bikers and dirt bikers helped the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) realize the recreational potential of the land and helped it become a tremendous asset for the valley. Many riders kick off their season with the ass kicking Original Growler race over Memorial Day weekend. Those who manage to snag an entry before it sells out can choose between the grueling 64-mile Growler course or opt for the Half-Growler. The race is almost all singletrack—similar to the original ‘80s race, Rage in the Sage. The racing community warmly welcomes newcomers.

“Helping with those events let us share our love for Crested Butte and our trails with people from outside of town,” Lisa Crampton said, a longtime local of Crested Butte. “It was all about us wanting to share our passion.”

Crampton came to Crested Butte in 1986 with a road bike, though it didn’t take much time before she was introduced to mountain biking. She’s been a steady part of the trail scene ever since, volunteering with Fat Tire Week for years and serving on the CBMBA board. Crampton, who works as a field marketing coordinator for Pivot Cycles, reflects how, at the time, she didn’t realize she was a part of mountain biking’s history.

“[It’s a] history that shaped the industry I’m still a part of today,” Crampton said.

Dave Ochs, CBMBA’s Executive Director, came to the valley in 2001. At the time, coming from the East Coast, he’d never been further west than Pennsylvania, and remembers being blown away by how friendly and welcoming everyone was. Like Cook and Wiens, Ochs moved to Crested Butte for snowboarding but instead developed what he calls “a raging mountain bike problem.”

“The passion I experienced when I first moved here hasn’t died a single lick. Our volunteers are our bread and butter. The energy is absolutely infectious.”

—Dave Ochs

As a new mountain biker, Ochs felt as though he’d “found his tribe” in Crested Butte. Three days after arriving, his new roommate invited him to a CBMBA volunteer trailwork day. It was National Trails Day, and the community was constructing a new section of singletrack called Tony’s Trail. Tony’s would eventually connect the town of Crested Butte to existing trails that lead to Mount Crested Butte and loop around town to the Brush Creek trails farther east. For Ochs, witnessing more than 150 volunteers show up to build trails was life-changing.

“I had only lived here for three days, and I had never seen a community rally around trails like that,” Ochs said.

A decade and a half later, in 2016, Ochs became the CBMBA’s first paid staff member. For 33 years the organization had relied solely on volunteers, something Ochs attributes to the community’s willingness to show up and give back—a testament to the love residents carry for their little slice of high mountain heaven.

“The passion I experienced when I first moved here hasn’t died a single lick,” Ochs said. “Our volunteers are our bread and butter. The energy is absolutely infectious.”

CBMBA typically tallies about 2,500 volunteer hours each season to help maintain and construct trails in the greater Crested Butte area. Work parties, most notably on National Trails Day and an annual overnighter, see between 100 and 200 volunteers. The combined population of Crested Butte and Mount Crested Butte hovers at slightly more than 2,000 people.

Like many mountain towns in the American West, the valley has seen a steady increase in visitation over the years which peaked during the COVID-19 pandemic. But even before record-setting visitation, impacts on the land had become unsustainable. As a result, mountain bikers and other outdoor advocates in Crested Butte are focused on taking care of what they already have and preserving the culture built on its rich history.

Wiens has managed to stay involved in local trail efforts even while working as the International Mountain Bicycling Association’s Executive Director. He places a heavy emphasis on maintenance in all facets of his mountain bike advocacy work and seeks ways to create more paid work for those who care for trails.

“There aren’t volunteers mowing the lawns at the ball field. There aren’t volunteers dumping chemicals in the swimming pool. It’s not volunteers driving the Zamboni at the rink,” Wiens said. “Trails are a legit, bona fide recreational infrastructure.”

CBMBA and Gunnison Trails have responded to the growing impacts of increased trail use and visitation by forming paid maintenance and stewardship crews that work on all trails in the area, including multi-use, motorized, and wilderness singletrack where bikes aren’t allowed. The crews are funded primarily through memberships and local donors and help complete much-needed maintenance in addition to the hard work done by a diehard community of volunteers.

This community’s dedication to trail work, along with a little bit of geological luck, combine to create an area unparalleled in its outdoor recreation access. Mountain pursuits are a way of life in Crested Butte and Gunnison and, for Wiens, a way of making the valley feel like a home to its people.

“My interest was to make this a great place to live and work and go to school,” Wiens said. “That’s what is important to me and always has been.”

Crested Butte and Gunnison’s mountain biking tradition is inextricably linked with the very birth of the sport. Now, its challenge lies in forging the next chapter of what it looks like to sustainably ride and recreate in one of North America’s most pristine areas. If the valley’s future is anything like its past, people and trails will only grow

more and more interwoven.