A New Epoch in Wheeling Broken Frames and 2,000 miles with the 25th Infantry Bicycle Corps

Words by Sakeus Bankson

The group looked exhausted as it entered the tiny frontier town of Billings, MT, their formerly crisp, bright-blue uniforms turned nearly black by the rain.

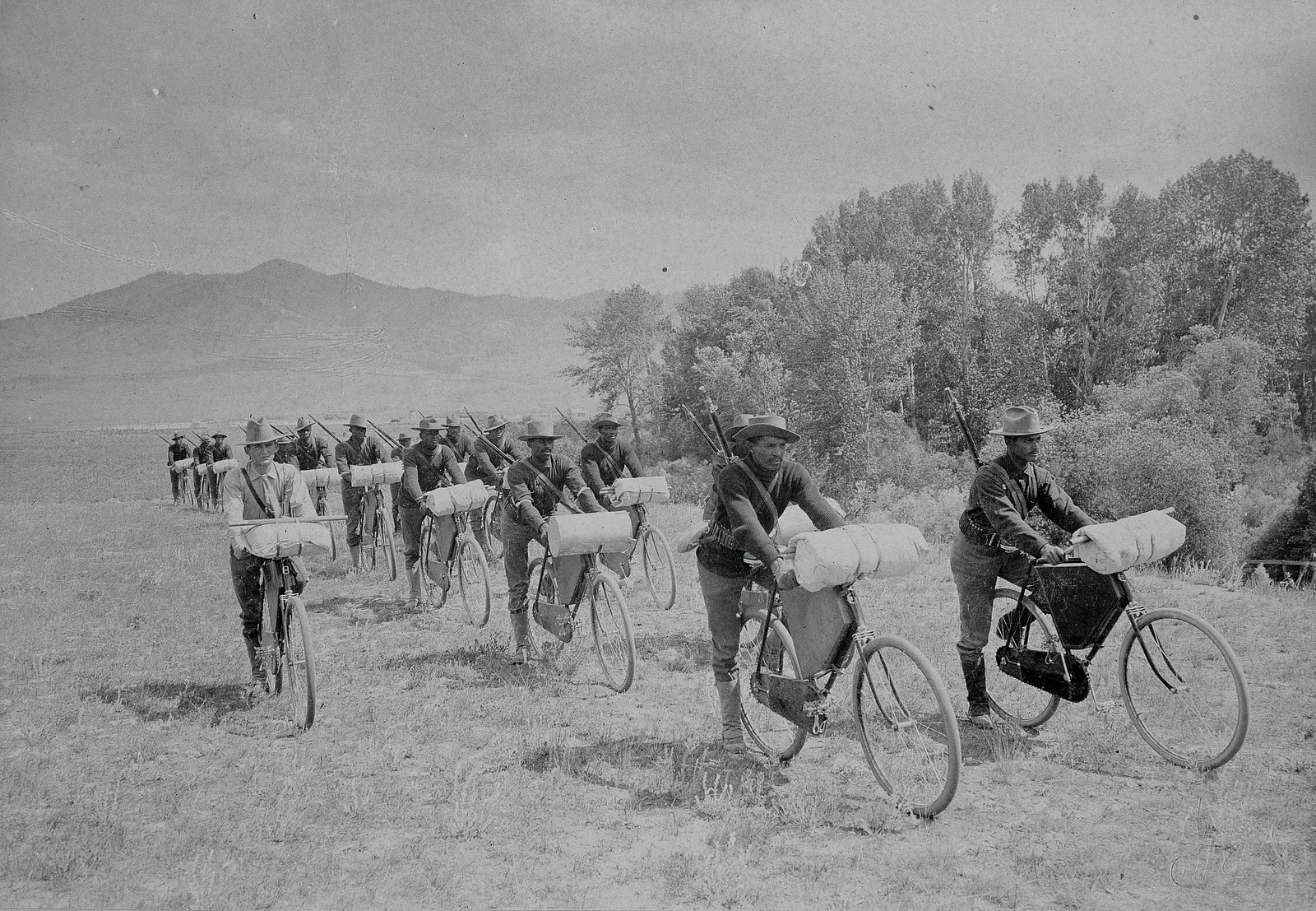

Mud spattered their legs, and their bulky packs looked as soaked as their jackets. But it wasn’t the color of their clothing or condition of their equipment that drew curious citizens to watch them pass. The visitors were on bicycles, and they were black. Even in cities, this would be an unusual combination. In 1897 Montana, it was downright bizarre.

The train of soldiers was the 25th Infantry Bicycle Corps, and they were on their way to St. Louis, MI. Known as the “Buffalo Soldiers,” the 25th Infantry was an entirely African-American regiment created shortly after the Civil War. By the early 1900s, the 25th would have gone on to become somewhat of a legend; in 1888, however, they’d been stationed at the Fort Missoula to keep them out of the way. So had their leader, Lieutenant James A. Moss. The Louisiana native had finished bottom of his class at West Point a few years earlier, and considering the town’s “backwoods” status, the Missoula post was not a prestigious one.

Fortuitously, these two misfit entities would be united by the newest fad in leisure to accomplish something amazing: complete one of the greatest journey’s in U.S. history, and show the world that the bicycle was a machine capable of amazing things.

By the 1890s, “wheeling” was all the rage in the U.S. The invention of the modern safety bicycle, chain-driven and with two same-sized wheels, had drawn droves of new riders, including Lt. Moss. As an avid cyclist, he saw the benefits this recreational machine had over horses; it was far faster than walking, and unlike horses didn’t eat, drink, get tired, or die. A number of European countries had already found useful ways to use bicycles as a military tool, so when Lt. Moss proposed the idea of an experimental bicycle expedition to Major General Nelson Miles in 1896, he was given the go ahead. The result was the 25th Infantry Bicycle Corps.

There was one problem. The Corps had 20 men but zero bicycles and zero funding to buy any. To overcome this, Lt. Moss struck a deal with the Spalding Bicycle Company—donate bikes to the expedition, and Spalding could use the Corp in their advertisements, and would be first in line to supply the military if the idea proved fruitful. After weeks of training on their new bikes, Lt. Moss and six volunteers set off from Fort Missoula in August, pedaling through the Mission Mountains to McDonald Lake.

It was a brutal endeavor. The already poor roads were made worse by bad weather, and the soldiers were unprepared for the mechanical issues unique to a bicycle. But four days and 126 miles later, the tired and wet party returned to Fort Missoula.

The second test trip happened just six days later, although “test” is misleading, as it took 23 days and covered the 790 miles between Fort Missoula and Yellowstone National Park. Despite carrying dozens of pounds of food and gear on their 35-pound steel bikes, as well a rifle and ammunition, the soldiers still made sure to enjoy some of Yellowstone’s wonders like Mammoth Hot Springs. After a wet and windy return trip, on June 14, 1897 the 25th— accompanied by a 19-year-old reporter named Edward H. Boos and surgeon James H. Kennedy—set off to see what their Spaldings were truly capable of.

The plan was ambitious, to the point of seeming impossible. The soldiers were to ride from Fort Missoula to St. Louis, MI, a journey of some 1,900 miles. And it didn’t start off promising. They left Missoula in a rainstorm, and upon entering the Rocky Mountains a few days later got caught in a snowstorm. Crossing the Continental Divide didn’t bring relief, either, as the steep roads out of the mountains were precariously muddy and forced the soldiers to walk their bikes to avoid slipping and falling. Nor did the plains of the Gallatin Valley, where the rivers and creeks were so swollen by mid-summer rains they had to carry their bikes through the mid-waist-deep waters. Even worse were the overflowing wastewater irrigation ditches, which splashed the soldiers with all sorts of refuse.

While riding through human filth isn’t something modern mountain bikers worry about, the 25th’s challenges are undoubtedly relatable, including the “header over handlebars” Boos describes one rider taking. The remedy should sound familiar as well—free drinks at the next bar, courtesy of a sympathetic Civil War veteran.

Sickness, water poisoning, 110-degree heat; each day brought new misery. They went through 17 tires and broke six frames, but even so the group still averaged some 50 miles a day, rolling, hiking and walking across the country at six miles per hour. Then on July 24th, after pedaling through the rain all morning, the 25th arrived in St. Louis to a hearty welcome from cheering crowds.

The 25th Infantry and Lt. Moss went on to earn distinction in the Spanish-American War the next year (after a huge send-off from nearly all the citizens of Missoula, for which the 25th had become a point of pride), and when massive wildfires raged across Montana and Idaho in 1910, the 25th was there to help put out the flames. As the superintendent of Glacier National Park put it, “the work performed by them could not be improved upon by any class of men.”

The bicycle as a military tool, however, was doomed to obscurity. Lt. Moss’ optimism wasn’t shared by the U.S. Army, and the only on-battlefield use it saw was back-up transportation during WWI and WWII. But the “Handlebar Infantry’s” legendary trip had accomplished something much more important: it proved the fancy new creation was far more than just a novelty.

“That bicycle ride of 2,000 miles from Fort Missoula to this city, over mountains, streams and deserts, marks an epoch in wheeling,” said reporter Everett Pattison in a St. Louis newspaper a few months after the trip. “In the first period, the wheel was a toy; in the second period, wheeling was looked upon as a sport; the third period has arrived when the world must acknowledge the wheel to be a practical, all-around machine.”