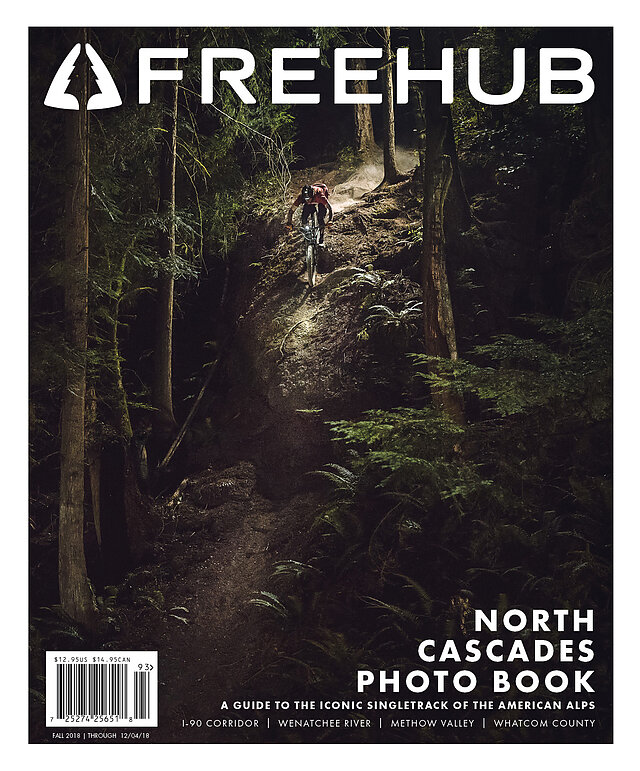

Welcome to Issue 9.3

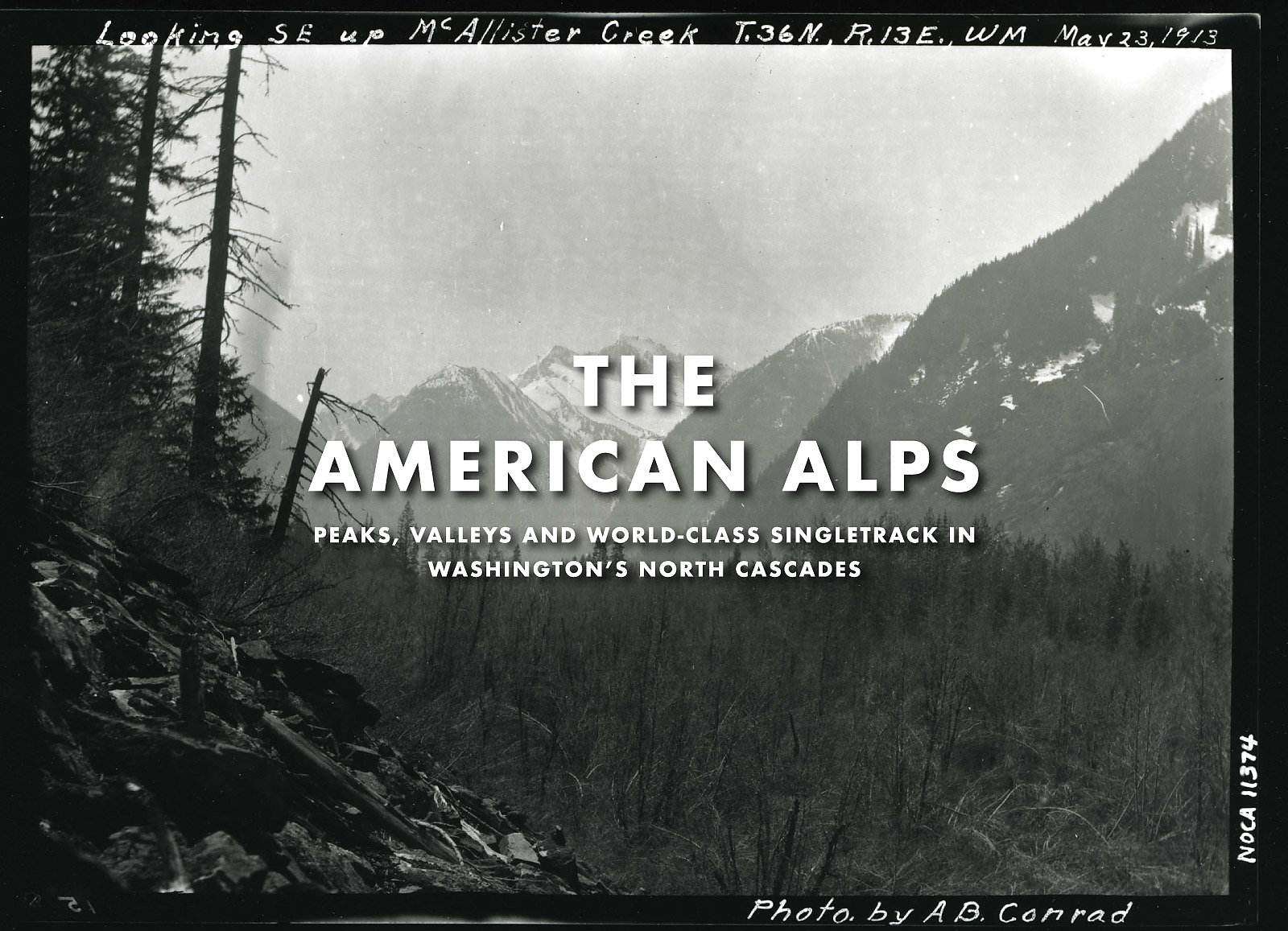

From the rainforest hills surrounding Puget Sound to the arid slopes of eastern Washington, the North Cascades make up an incredible and diverse region. At Freehub Magazine, we’re lucky enough to have these mountains—also known as the American Alps—in our back yard, and can testify to the amount of opportunity and beauty within. For our fifth annual Photo Book, we figured there was no better place to explore, document and share. The North Cascades Photo Book is a guide to the iconic singletrack of the American Alps.

One time, when my mom was in college, she saw a guy get his ear bit off at the World-Famous Brick Saloon.

There’s a 23-foot-long running-water spittoon under the bar, so the miner men could pee without leaving their beers. On one of my own visits, apparently Justin Bieber had been there minutes before. Anyone who has spent time at the Brick has stories and, though I feel relatively confident in the validity of mine, I’ve come to realize that the Brick is like a game of two truths and a lie: amazingly strange stories mixed in with a few equally strange and indistinguishable embellishments.

To better understand the self-proclaimed oldest-operating saloon in Washington State, you must take a look at the town in which it sits. With less than 1,000 citizens, Roslyn is a tiny, former coal-mining town in the arid foothills of the Cascades, surrounded by beautiful ponderosa pine and Douglas fir forests that smell sweet when it finally rains. Tall, skinny wood houses tower over the quiet streets. It’s the type of place an old dog would walk across the street in front of your car real slow, making eye contact the entire time.

Words by Nora Jacobs | Photos by Mary Hone

Every year during the first weekend of May, the ferry to Orcas Island is packed with mountain bikers.

An assortment of vans, trucks, minivans and Subarus fill the Anacortes terminal’s 16 lanes, waiting for their chance to start the hour-long motor to the forested cluster of the San Juan Islands. It can be a long wait; it’s the last weekend before Orcas’ summer bike closure, and from the DH, enduro and XC bikes stacked and packed into the mob of vehicles it has the makings of one big party.

The weekend’s popularity might be due to the ferry ride, which makes the island feel a world away. Or maybe it’s having a paved road to the top of the 2,398-foot Mount Constitution and the ability to pack a shuttle truck beyond the brim. It could also be the trailhead lake-side camping, a mountain bike factor that can rival an all-inclusive resort. Or maybe it’s the miles of singletrack falling from the summit of the San Juan’s tallest peak. Whatever the reason, mid-May on Orcas Island is a singletrack bender.

Words by Jann Eberharter | Photos by Ian Terry

They were scattered on both sides of the dusty, washboard trail like cast-off plastic bones, their cylindrical shapes bulging from the North Central Washington heat.

Most the water bottles were clear or white, and we searched through the torn-up mat of ponderosa needles for the odd spots of color. Those were the best. They were usually from hallowed locales like Moab or Durango. Places we wanted to go. Places we dreamed of riding.

It was 2001, in the tiny tourist town of Chelan, WA. The bottles were remnants of a regional mountain bike race held at the local Echo Valley ski hill, shaken from the racer’s frames on this particularly bumpy section of trail. While neither myself, my brother, nor our friend Cody actually needed any bottles, for three small-town, teenage wannabe mountain bikers, they were tokens of a larger, more exciting world, a taste of cutting edge in our backwoods bubble.

Or that’s what we thought at the time. With our attention on our recycling bin, we missed one key detail: we forgot to look up. If we had, we’d have realized the surrounding terrain was some of the most impressive in the country: the North Cascade Mountains, nicknamed "the American Alps" for their archetypal peaks and Sound of Music-esque alpine meadows. Even then they were packed with trails of all types, a dreamland for any ambitious rider with a taste for an adventure. We just hadn't noticed yet.

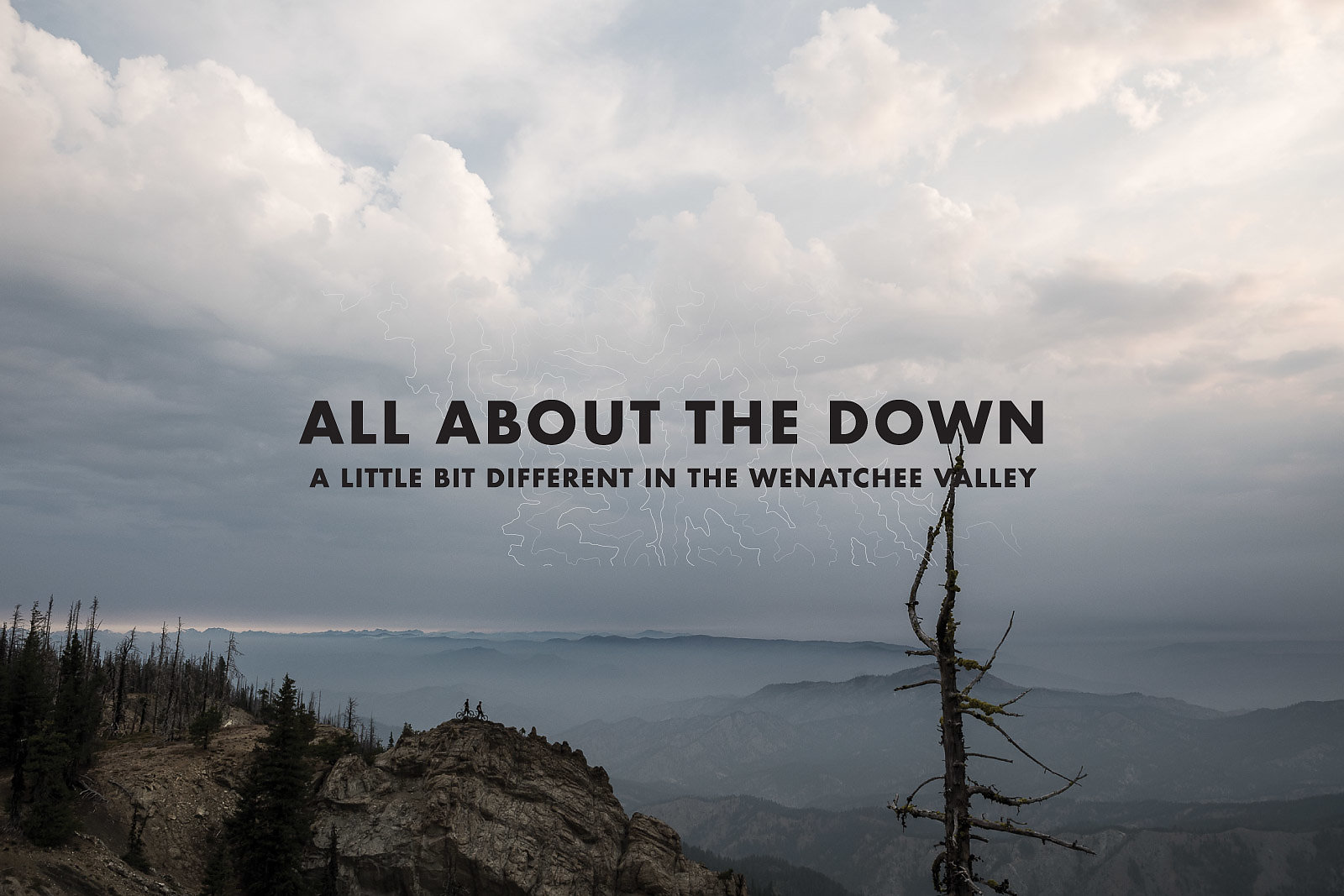

Words by Sakeus Bankson

When I first moved to Seattle 10 years ago, I was admittedly apprehensive about relocating to “the big city.”

I’d been living in the small mountain town of Durango, CO, where I’d grown used to waking every morning to blue skies and incredible singletrack right out the front door. In the Northwest, days began with gunmetal gray skies (and oftentimes rain), a much larger population, and the need to drive to go mountain biking. I’d come from a place with every kind of trail imaginable and an amazing community of talented riders. Here, I didn’t know the trails or have anyone to show me where they were.

As I began my search for new singletrack and a new crew, it didn’t take long to find some gems close to the city and a few folks to ride with. I quickly met people in the bike shops, out on the trails and in the parking lots—even in the dead of winter when the short days offered only a few hours to get loose and muddy in the dense Pacific Northwest woods.

Words by Darren Dencklau | Photos by Riley Seebeck

I remember my first real mountain bike ride.

I was 16, and had just moved from Tacoma, WA, three hours east to the tiny, quasi-Bavarian town of Leavenworth. My new friend, a local named Dan, handed me a Specialized FS-something and told me to chase him and his buds down a nearby trail. Wanting to fit in and not knowing any better, I took the bike and followed him to the top.

To my rookie mind, the ribbon of singletrack was steep as a ski run and seemed narrow as a tightrope, confined to a knife-blade ridge with rocky exposure on either side. I was terrified. And I was inspired. I watched my new friends skid down the mountain, ride fall line down sandstone slabs and cliffs, and flow through pine forests on a wispy trail of tire tracks. My fingers slowly loosened on the brake levers and I let myself accelerate, looking for the next opportunity to dump speed before letting loose again.

Words by Reese Bradburn | Photos by Scott Rinckenberger

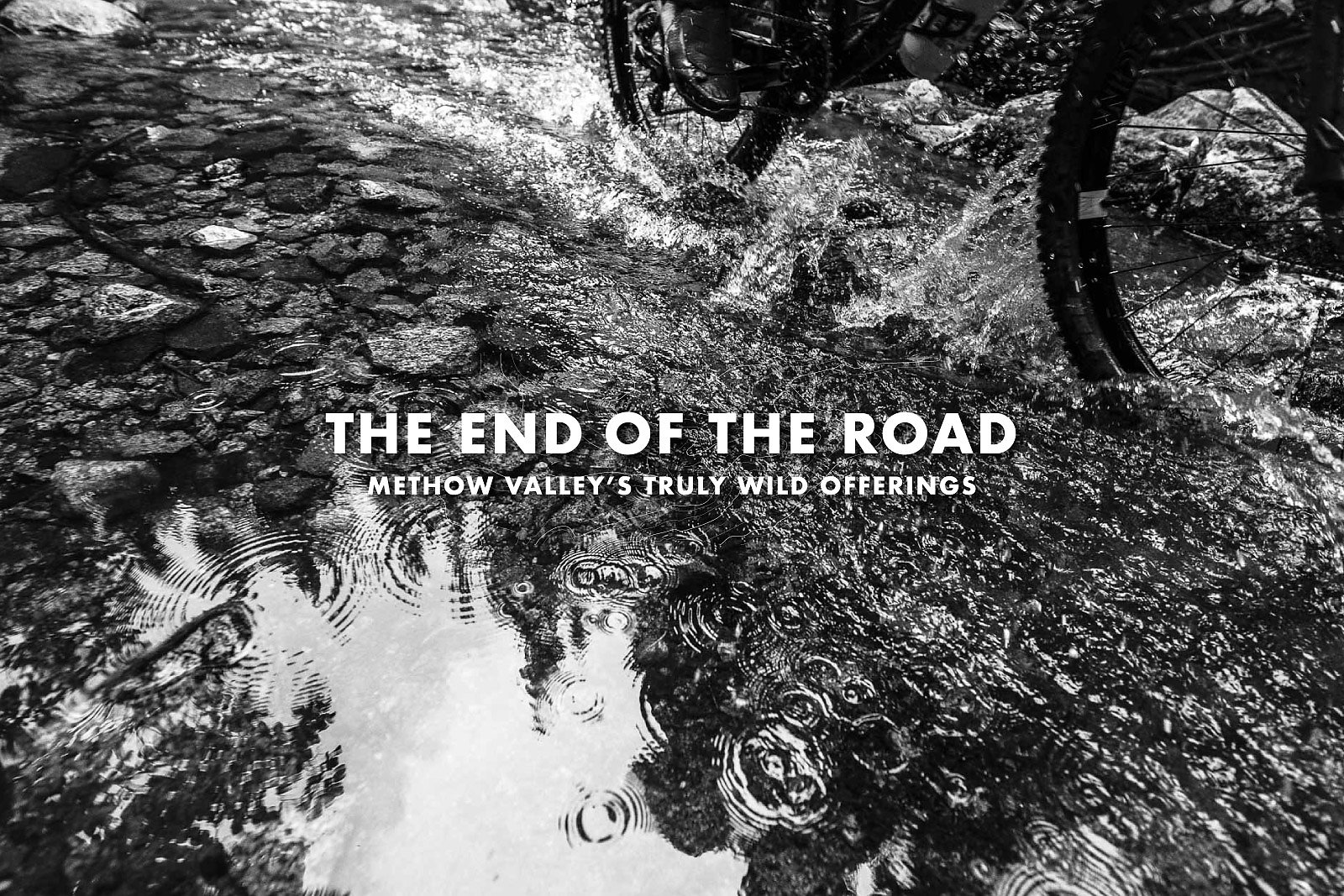

Main street may be paved, but it’s not hard to imagine John Wayne moseying past the wooden boardwalks and weathered storefronts of Winthrop, WA,

headed toward the swinging doors of Three Fingered Jack’s Saloon as he prepares for a shoot-out with some villain inside. Everything from the general store to the gas station to fonts on the signs could be pulled straight from an old Western movie, an appearance the town has cultivated for more than 45 years.

The irony, however, is that while Winthrop’s current appearance may be artificial, the iconic cowboy style was actually born in this tiny, rural hamlet of barely 450 people. Owen Wister’s 1902 novel, “The Virginian,” is regarded as the first true American Western, and was inspired by his honeymoon to Winthrop. More than a century later, Wister’s muse may seem far tamer, but it remains a frontier for backpackers, rock climbers, mountaineers and—most recently—mountain bikers searching for rowdy, wild terrain.

Words by Sakeus Bankson | Photos by Paris Gore

I can’t sit on my couch.

The tick of spinning hubs is too distracting. It’s an all-day, every day parade past my front lawn during the summer. Old bikes clank, new bikes hum. Young, old, somewhere in between, they roll by smiling, a bit dusty, dogs in tow. Solo, in groups of six. Inevitably, someone will recognize my van and stop by.

“Wanna ride?”

“I just wanna watch the game, man. Maybe do some gardening. But yeah, I got time for a quick lap I guess.”

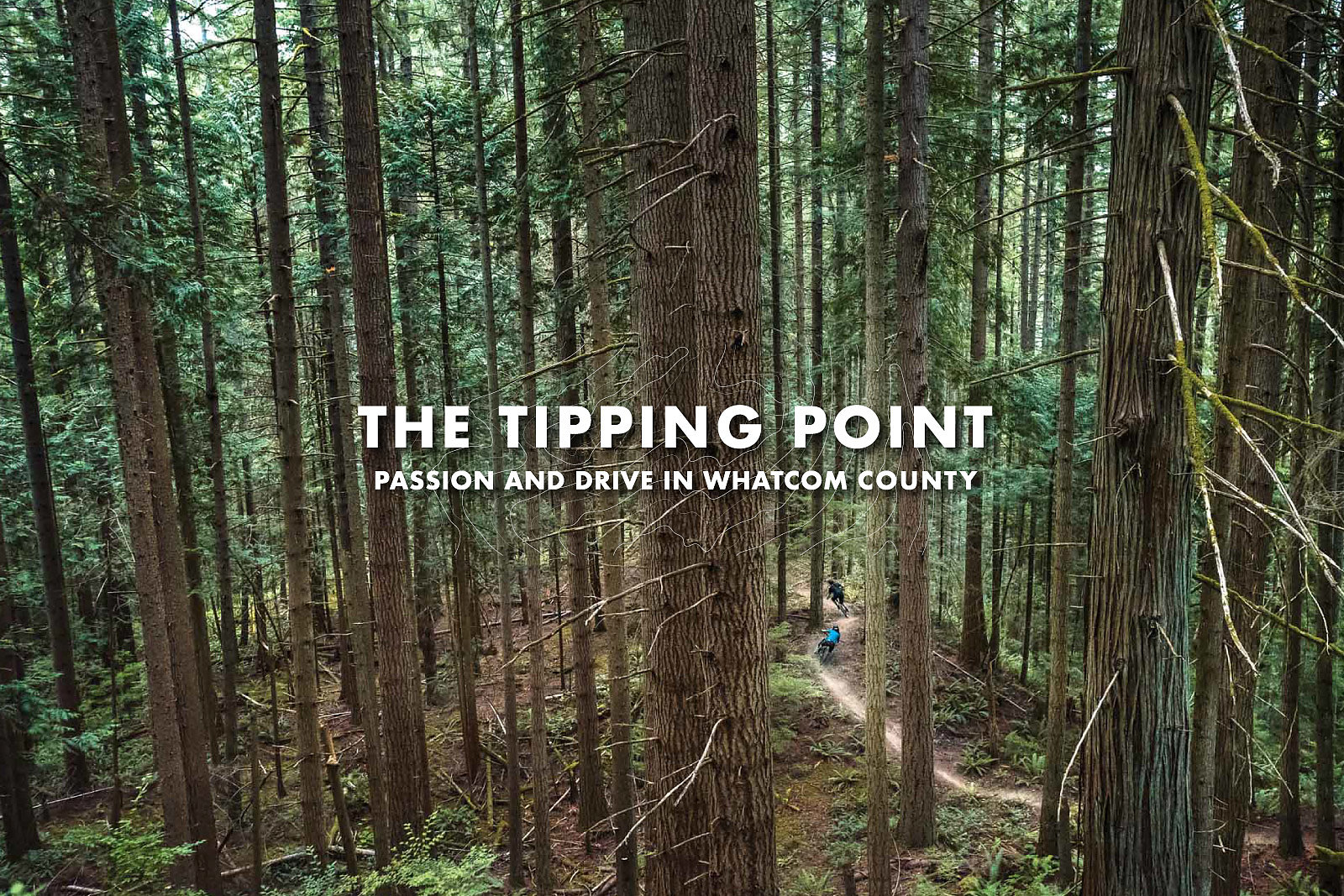

My street’s only a block long. It’s right off Birch, the main thoroughfare to the north side of Galbraith Mountain (officially part of Lookout Mountain). The hub of Whatcom County cycling, it’s right in the city. No more than a 20-minute pedal from most of Bellingham. The nickname comes from Galbraith Lane, where the first handful of folks starting building trails in the mid-80s. It stuck. They formed the Whatcom Independent Mountain Pedalers, or WHIMPs, when trail access became an issue.

Words by Colin Wiseman | Photos by Eric Mickelson