First Light A Curious Creep Down The Wormhole of Framebuilding

Words by Skylar Hinkley | Photos by Kipp Hinkley

Dimly lit by a sole bulb and traces of moonlight, I hunched over my workbench, eyes fixed on the soft glow of my phone. On the screen a blurry, middle-aged man wearing greasy blue coveralls and gold-rimmed glasses glanced up at the camera, as if to make sure I was still paying attention, while he slowly demonstrated the correct way to turn a knob.

It was my fourth time watching this video and, by now, his mannerisms felt familiar. When the man held up a rubber hose to illustrate how to check for leaks, I mimicked his Southern drawl as we both declared in unison, “Safety rules are your best tools!”

Learning online was nothing new for me, but this wasn’t like figuring out the proper way to bleed brakes (olive oil is not a substitute for mineral oil), or how to give the world’s greatest high-five (look at the elbow not the hand). This was different; I was about to open the valve on a thick steel canister containing more than enough flammable gas to engulf my tiny workshop in flames. And without anyone around to talk me out of it, or at least check if I was doing it right, I pressed on.

The igniter’s sparks met the hiss of acetylene gas at the end of the torch and erupted violently into a grotesque orange flame spewing smoke everywhere. My heart raced as I choked on the toxic vapors. A black cloud began to fill the room. Then I remembered my YouTube training. I cracked open the oxygen valve and the torch flame instantly transformed into a thin, blue streak of light.

In awe, I gently waved the fiery wand back and forth. Though it looked soft and feathery, I knew it was burning at more than 4,000 degrees Fahrenheit. As the heat radiated out and warmed my face, I felt a grin pulling up on the corners of my mouth. I broke out laughing hysterically—until a few tears of joy rolled down my cheeks. I was drunk with power, like a caveman discovering fire and preparing to make his first steak.

Lighting up that torch was a major milestone on my journey in framebuilding, but it took over a year to even get that far. The early days were dreadfully slow and the learning curve steep. At times it often felt more like a Sisyphean punishment than a hobby I was actively choosing to do. Looking back, I guess I didn’t so much choose framebuilding as it chose me.

It was a cold winter Wednesday, and my teeth chattered while the rest of my body quietly shook. Standing next to me in a similar state, Dale Lord lifted his fingers to his face and blew warm air into his hands before rubbing them together. The sweat from our brisk ride to work had nearly turned to ice while we waited for someone to unlock the doors at Kulshan Cycles, a bike shop in Bellingham, Washington where we both held jobs as mechanics in 2016.

“I’m going to make a robotic hamburger vending machine in San Francisco,” said Dale, matter-of-factly. I turned toward him with a puzzled look but before I could reply, the door swung open.

Once inside, our hands warm and brains thawed, he laid out his plan. To my surprise, he really was leaving town to make an automatic patty flipper. More surprising still was that he wanted to entrust me with his collection of specialty framebuilding tools before his departure.

We only worked together for a year or two, so leaving $10,000 worth of tools in my care was a big leap in our friendship. I was honored and extremely grateful though, looking back, I wish I had taken the time to learn some skills from him before he left. But the torch had been passed and now I needed to figure out how to use it.

Eager to get started, I took to the internet and mashed keywords into my search bar. As I scrolled through the results, my eyes glazed over. The section of the internet devoted to learning how to build frames seemed to be stuck in time—a simpler, more pixelated time when like minded people gathered exclusively in forums, before media could be considered social and Flickr links were still the gold standard for sharing images. Returning to those spaces of the web now feels like visiting an archeological site to see finger paintings of stick figure men hunting stick figure animals. It makes you wonder how ancient people made do with so little.

After sifting through the remnants, I did find some online forums still held value. One of the quintessential framebuilding forums, Velocipede Salon, administered by the infamous Richard Sachs, is an exceptional community of framebuilders eager to share information and answer questions. Users can, in one section of the site, ask a question and only members with the “mentor” designation can respond. This is wise, especially for a trade in which every tool, if used improperly, can cause death or severe injury.

However, when I was first getting started, it wasn’t very inviting to sift through the often pictureless pages of dated conversations shared between strangers, many of whom never bothered to fill out their profile page. Who is cjroot2004? Or juggaloslaya? Do they really know what they’re talking about?

“The internet is a crazy thing,” wrote progressive bicycle designer, Peter Verdone, in a 2015 blog post providing advice for aspiring framebuilders. “It’s a place where people who have no idea what they are talking about can be called experts, and experts be called fools.”

Perhaps the lack of modern resources to newcomers should not have come as a surprise. After all, the type of torch and file framebuilding I was attempting is older than old school. In fact, it traces back to Mesopotamia at the beginning of the Bronze Age, circa 3000 B.C. Though the bicycle would not be invented for another 4,800 years, the Sumerians were already making intricate objects out of tubular metal, brazed together with molten bronze and chemical fluxes—exactly what I wanted to do.

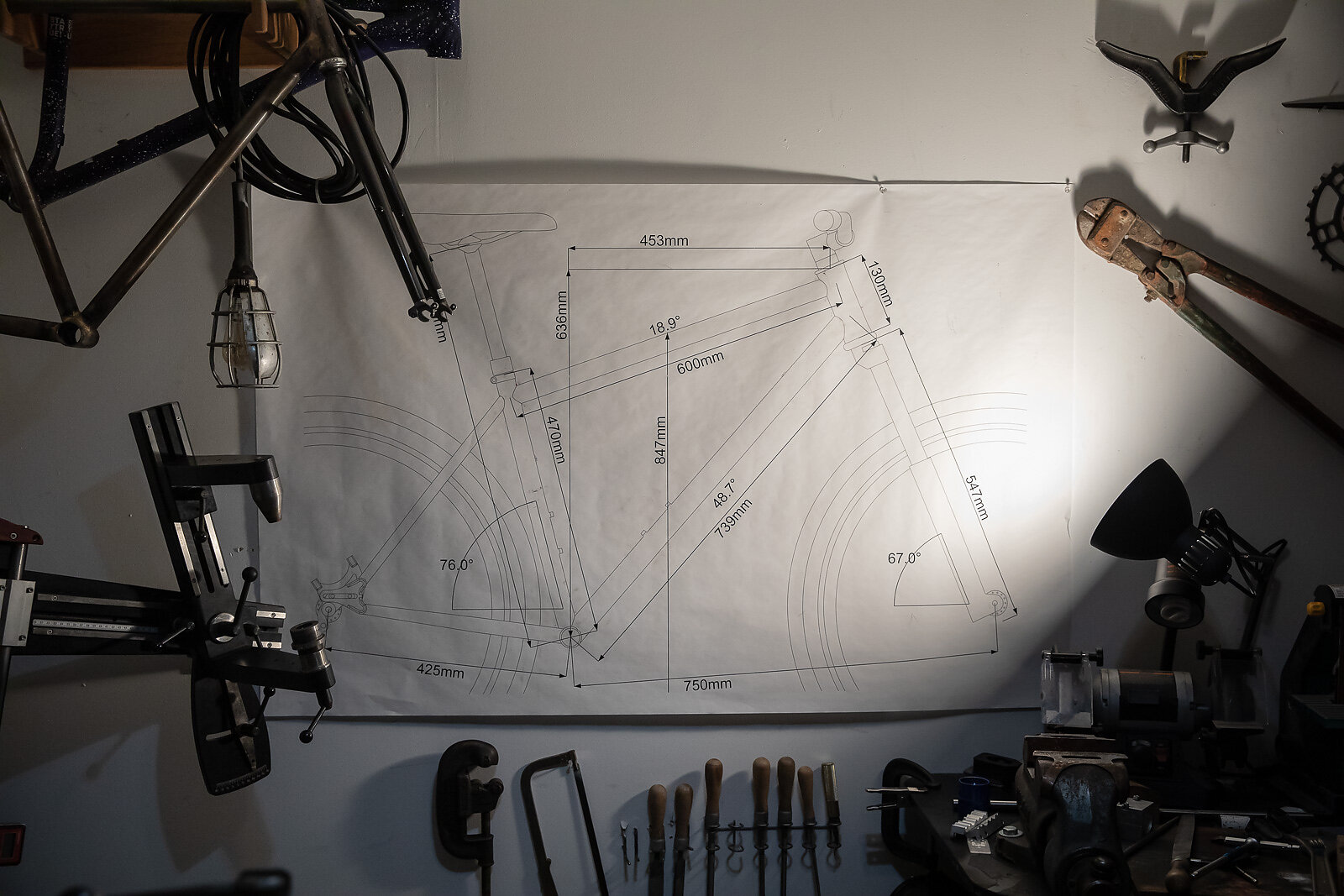

Admittedly, I did find a few young builders starting to create how-to-style video content in the framebuilding sphere. Pithy Bikes and Cobra Framebuilding were using computer-aided design (CAD), milling machines for precise cuts and tungsten inert gas (TIG) welders for joining tubes—all things I did not have. Most of the people I could find still shaping tubes with hand files and connecting them with melted bronze were old guys—not quite Mesopotamia old—but old enough to not be posting high-quality videos on the internet.

One such old guy I came across in my research was a famous Colombian builder named Tinno. In the ’60s he wanted to build bikes so badly that he translated an entire welding manual from English to Spanish, word by word, with a paper dictionary, just so he could have a little bit of information to go off of. That task alone took him three months. And here I was, whining about not being spoon-fed enough perfectly tailored YouTube videos.

The truth is, the more I came to terms with how fraught filled of a niche framebuilding actually was, the less I wanted to do it. So, feeling deflated, I decided to just pack it all up—or, rather, leave it unpacked. My hefty collection of tools stayed in the corner of a small shed and remained untouched for the rest of the year.

The following spring, back at Kulshan Cycles, a coworker we called Baby D shouted at me across the store, “Hey Sklar! [My nickname around the shop] I can’t believe you won an award at NAHBS and didn’t tell me!”

He knew I was having a hard time getting started with framebuilding and was messing with me. The North American Handmade Bicycle Show is a trade show and competition for the who’s who of framebuilding, and I had absolutely nothing to do with it. But Baby D, with a smirk, gestured for me to come see what he was looking at on the computer. What I saw was the photo of a young man with cherubic features, holding a curvaceous hardtail painted pale green, with the word “Sklar” in gold letters adorning the downtube. At only 23 years old, Adam Sklar had won the Best Mountain Bike category at the show.

I felt both envious and inspired. This young guy was making beautiful bikes, and they were branded with my nicknamesake. It felt like a sign. A life parallel to my own was asking me what the heck I was waiting for.

I later learned that Adam held a degree in engineering and had been mentored by veteran framebuilders Walt Wehner and Carl Strong. This insight helped tamp down some of my delusions of grandeur and better understand his success, though I became especially intrigued when I read an interview with Adam in which he mentioned building his first bike with rudimentary tools on the floor of his parents’ garage. His only aid? YouTube videos.

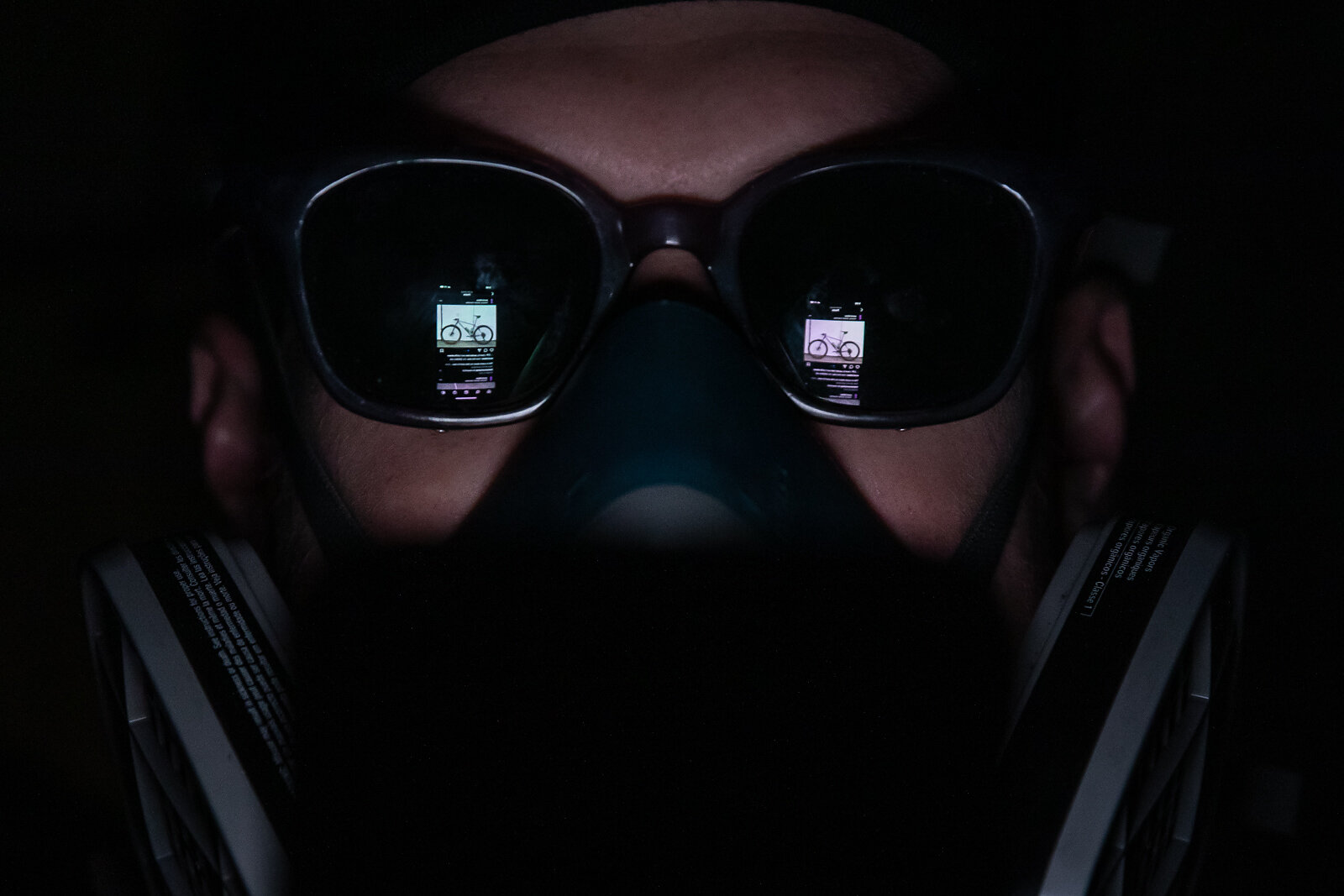

There it was. Proof it could be done. Yet, my biggest takeaway ended up being a small mention Adam made about Instagram. I hadn’t thought to look on the ’gram for advice, so I decided to grab my phone and take a peek. In that moment I encountered something I had yet to find during my escapades down the framebuilding rabbit hole—a tangible sense of community.

Following one framebuilder led to another, and another, and soon my feed filled with images of raw metal tubes turning into bikes. It was transcendent. Not only were people posting great photos and videos of their process, but many of them seemed to also know each other, or at least they acted friendly in the comment sections by regularly sharing words of encouragement, a thoughtful suggestion and the occasional nerdy joke. When Cjell Mon (@monebikes), one of my favorite builders, posted a series of magazine-quality photos of a single, rectangular sheet of plywood with wheels and a seat and handlebars attached to resemble a bike, someone in the comments asked, “How do you adjust the headset?” Cjell replied, “Wood glue.”

For a while I just sat back and watched, taking it all in. Seeing photos of highly refined bikes from masters of detail such as Brian Chapman (@chapmancycles) or Nao Tomii (@tomiicycles) was always a pleasure, but the mediocre builds and practice pieces often shared by newer builders helped the most. Seeing someone else’s failure—and their progress—made me less fearful about getting started myself.

MORE OFTEN THAN NOT, EMERGING MYSELF IN THE FRAMEBUILDING COMMUNITY OF INSTAGRAM WAS AKIN TO HANGING OUT, TALKING SHOP.

After I secured a space to set up the tools and start making my own mistakes, I began reaching out for help and was surprised at how generous people in the community were with their time. Everyone, established professionals with a multiyear queue for custom builds and other folks like me just trying to make a few frames for themselves, took time to answer my questions with care. Sure, the replies I received weren’t quite on the level of, say, Rainier Maria Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet, but nothing is these days.

One of the first builders I reached out to was Yuli Yuliyanov Iliev (@Rolap_Cycles) in Spain. I was originally drawn to his work because he posted short videos demonstrating his exceptional skills in brazing. When I sent him an inquiring message he responded with some pointers and professed the value of inline flux. He had been working at Brompton, a folding bike manufacturer, for the last two years, and said that when he started, he “didn’t even know how to hold a torch.” He went on to reiterate that “the key is a lot of practice” before asking if I had any pictures of my work. I was enheartened by his encouragement and interest.

Another builder, Anthony Bacon (@ya.boy.toni), posted stories describing in detail each step of a build he was working on. It was the most acutely instructional series I’d come across on Instagram, so I messaged him to let him know how much I appreciated it. He was also framebuilding just as a hobby and told me that he “struggled a lot getting started because [he] couldn’t find much beginner info.”

More often than not, emerging myself in the framebuilding community of Instagram was akin to hanging out, talking shop. Swiping through stories provided a whirlwind of design ideas. A smorgasbord of tool talk. A menagerie of miters and fillets and jigs. In one clip, Joe explained how he used thermal expansion by way of an induction heater to fit a carbide helix end mill snugly into the tool holder of his CNC machine. Then, right as he started to lose me, the Bilenky boys swooped in, excited to show me how they attached a butterknife to the end of a cordless drill to upgrade their flux stirring system. I was going to tell them how great that setup would be for a fresh jar of chunky peanut butter but, before I could, Danielle wanted me to see her NOS Ghostbusters horn with a handlebar clamp. I mean, it was obviously the coolest thing I’d seen in the last two seconds, but I was starting to feel overstimulated and quickly swiped back to my home screen. Then the lowgrade anxiety came—nervous that I would miss some fresh content—so I hopped back on to see what Em was up to.

Yes, the attention economy is doing untold damage to the fabric of our very existence. Yes, I lose massive amounts of time and autonomy to feeding the ravenous algorithms of Instagram. And, yes, I deeply appreciate all the framebuilding fanatics I’ve come to know there. It was amongst their posts about creative projects and behind-the-scenes insights that I found so much motivation to keep going when I wanted so many times to give up. If there is still value to social media—that, is it.

I’m not the only one who feels this way. United by a growing sea of builders and fans, framebuilding is riding a cyber swell of interest. Thanks to platforms like Instagram and people like John Watson, founder of the Radavist, a website that often showcases hand-built bits of gear, custom one-off and boutique small-batch bikes are back in the limelight. There’s even a biweekly podcast—the telltale sign it seems of cultural foothold in the modern era—called Shut Up and Build Bikes.

But what really makes this such a ripe time for framebuilding is not its growing online presence, it is the growing number of resources. The skills required to participate in this once-fading artform are now available to the point that amateurs can build frames at home with a few basic bits of kit.

Since I began, online resources have grown rapidly. One of the best video series was created during the COVID-19 pandemic by Mountain Bike Hall of Famer and legendary framebuilder, Paul Brodie. Paul taught a framebuilding 101 seminar at Fraser Valley College for several years but, when that shut down, he took to YouTube with a former student to make the information available online. The results are admirable, this humble Canadian performing his craft truly is a sight to behold.

The comment section is filled with the usual over-the-top praises, “I’m pretty much addicted to watching your videos!”; “An absolute joy to watch a real craftsman at his work. Well done Paul!” Other commenters strike more directly at the heart of contemporary web culture.

“Thank you for all this content,” writes one user in a video about fillet brazing, “Best rabbit hole I’ve gone down in a while.”