Aprés-Ski Rich Snow Traditions Set The Stage For Vermont's Mountain Biking Boom

Words by Bryan Rivard

In the last three decades, mountain biking has exploded across Vermont.

What started as small communities of passionate enthusiasts has grown into a mainstream statewide culture. The sport itself grew in tandem, rising from its adrenaline-fueled beginnings into an all-encompassing lifestyle—a weekend family adventure, a catalyst for rural tourism, even a driver of real estate sales.

Vermont is unique. As a state with a small footprint, modest-sized government land holdings and a mosaic of privately owned property covering most counties, the Vermont mountain bike scene as it exists today, shouldn’t.

But Vermont is stocked with Vermonters. Passionate, determined and embodying the wry unofficial state motto of “live free or let’s talk about it,” they were the ideal people to take on a set of seemingly insurmountable obstacles to turn the improbable into the impressive, partly because of how perfect Vermont’s terrain is for mountain biking, and partly because they were already veterans of launching state-shifting industries. Nearly a century ago they’d done it with skiing.

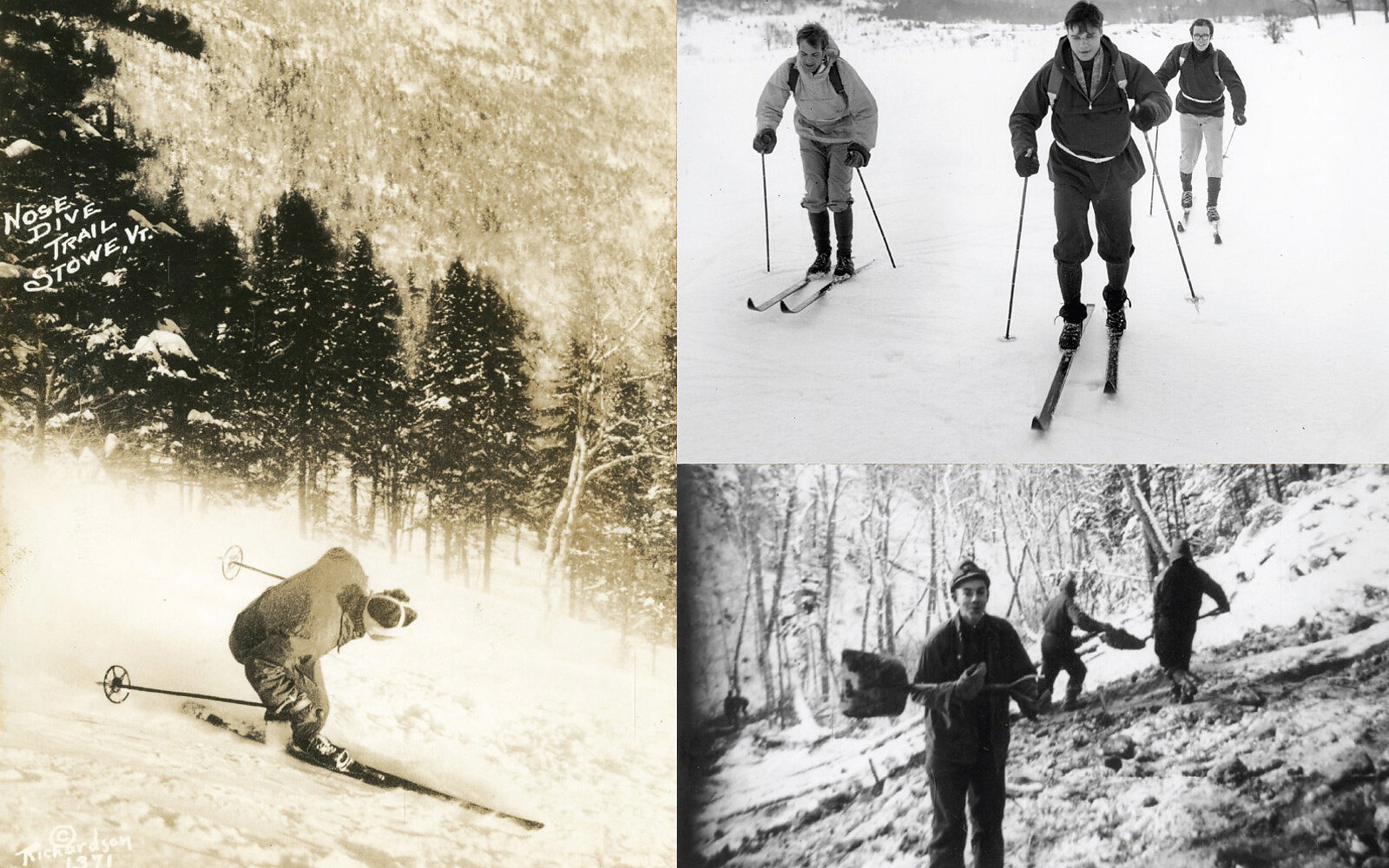

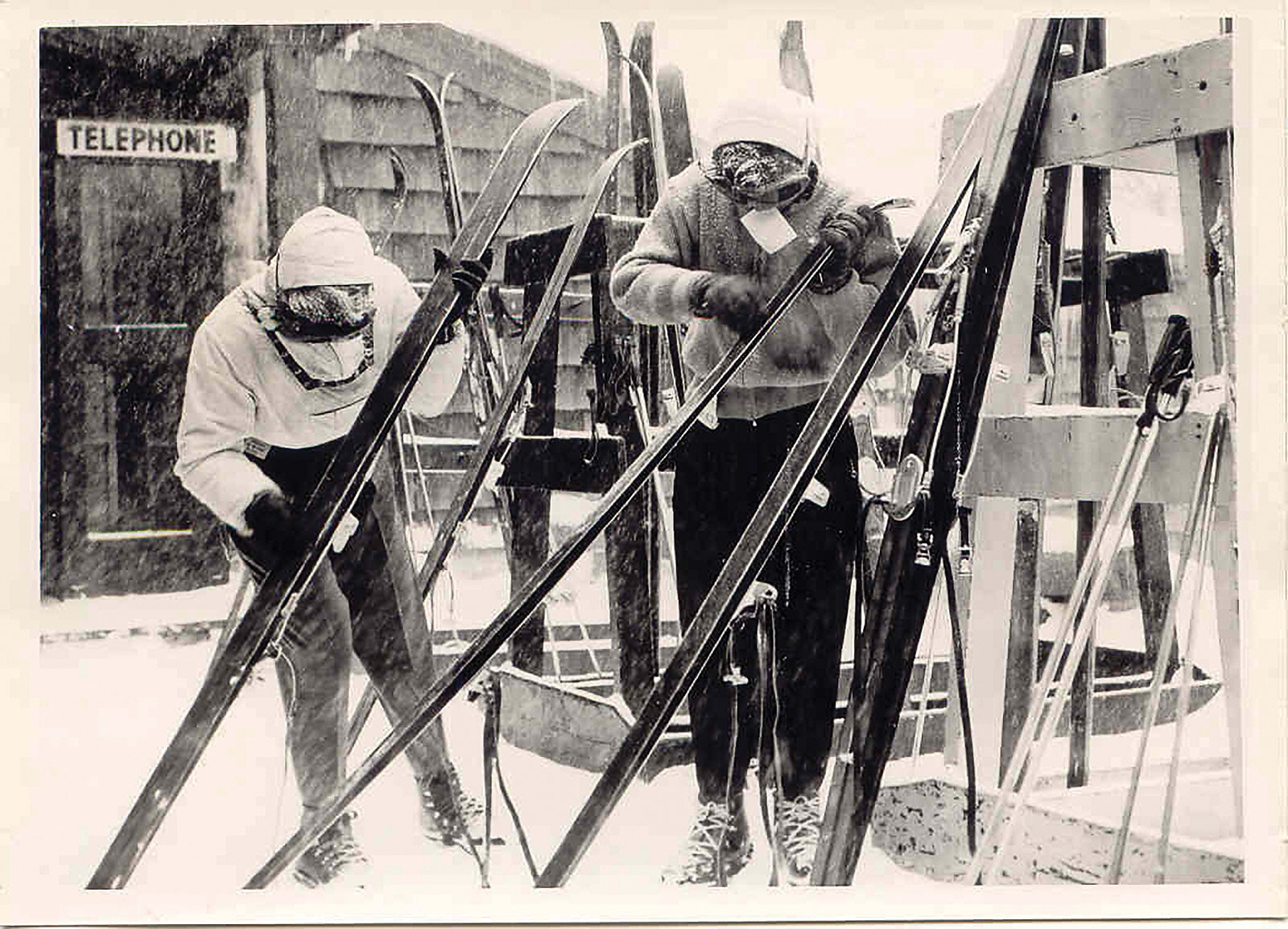

Cross-country skiing enjoyed a decades-long history in New England before alpine started to capture a growing amount of attention. Skiers and ski evangelists increased in numbers across Vermont, forming community clubs and race associations while college teams to the south traveled north to hold events long before the Great Depression upended the country, spurring jobs programs that activated government workforces such as the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC).

Having witnessed the enthusiasm of local groups, agency figures made the case for similar initiatives and once mobilized, the CCC set about completing several projects, including cutting hiking and ski trails across Vermont. Channeling the effects of the New Deal, Vermont’s focus on recreation infrastructure set the stage for a host of outdoor activities in the decades to come.

“Vermont has a long history of being outdoors—and labor,” says Tim Tierney, a director at the Vermont Department of Economic Development and former executive director of the Kingdom Trails Association. “Making maple syrup, stacking stones, haying fields—that labor is a part of Vermont. Vermonters seem to love it as much as the play.”

The CCC projects improved access to summer and winter trails and, with each passing milestone, Vermont’s focus on the outdoors seemed to shift into a higher gear. After World War II, soldiers from such units as the 10th Mountain Division brought their alpine training home and used it to fully engage with Vermont’s wilder spaces.

As skiing, trail construction and a general outdoor culture increasingly became a cornerstone of Vermonter identity, the economic growth of the 1950s brought a rapid expansion of ski resorts across the state. Leveraging the growing interest in riding planks down snowy mountainsides and advancements in lift technology, the resort model of skiing removed barriers for people who might not have otherwise considered the sport

The rise of Sugarbush and Bolton Valley, resorts opened in 1958 and 1966 respectively, further expanded the prevalence of Vermont’s ski culture. Construction, ongoing maintenance and increased skier traffic at new resorts required roads, which would provide access points for trailbuilders and mountain bikers in the coming decades.

Whatever the cause, the confluence of effort, excitement and appreciation of the outdoor aesthetic caused something to click in the state’s collective psyche. Outdoor activities—skiing in particular—gained momentum throughout the 20th century, melding Vermont’s identity with a signature passion for the outdoors that its residents continue to hold.

Until the late 1980s mountain bikers and cross-country skiers in East Burke basically had two options: use logging roads left behind after timber harvests or ride errant sections of trail at the abandoned Darion Inn Ski Touring Center, trashed during the logging exodus of another local company.

In 1988, John Worth, a ski patroller and lead planner for Burke Mountain’s glade trails, opened East Burke Sports. As the owner of a ski shop, Worth didn’t want to shutter half of the year, so he decided to make a play for a four season business and gambled on selling mountain bikes in a town with nowhere to ride them.

The idea of cutting mountain-bike-specific trails was an exciting departure—and risk.

With a handful of fellow fat-tire devotees, Worth started building trail mostly to reconnect sections of cross country ski loops destroyed during the timber harvest. Before long, the trail system had a lot of people using it, and Worth was drawing a lot of maps while growing increasingly nervous that landowners would shut it all down.

“We didn’t even know who owned some of those properties,” Worth says. “That’s when Doug approached me and said, ‘Hey, you should turn this into a viable trail system—a legal one.’”

Doug Kitchel, the former general manager of Burke Mountain and someone who “pretty much knew everybody,” volunteered to talk to the area’s landowners. Despite Worth’s initial concerns, the owners all agreed to allow access for the trail system (according to state law, unposted land is considered open by default, and Vermont’s outdoor ethos manifests in strong liability protection for those who allow free public access to their land).

The result of that initial collaboration is a multi-use trail network that spans more than 100 miles, a collection of agreements with 104 local landowners and a historical, as well as physical, connection to Burke Mountain that grants visitors the choice of riding endless-feeling cross-country singletrack at Kingdom or hitting Burke’s gravity-oriented trails. The area has defined itself as a hub for four-season recreation.

“We like to say, ‘When the skiing’s bad, the fat biking is good,’” says Abby Long, executive director of the Kingdom Trails Association. “There’s a lot of crossover in the community—skiers and mountain bikers… the sports complement each other really well.”

Visits to the trail system jumped from 7,000 in 2004 to 140,000 in 2019, with Kingdom Trails contributing $10 million in economic impact to the local area annually. Success brings new challenges, but hard work and collaborative effort aren’t in short supply in Burke. Volunteer trail ambassadors, an ongoing focus on sustainable growth and strong relationships with the private landowners who make the network possible show what’s attainable when a community commits to an idea it truly values.

As Northeast Kingdom was expanding from a cross-country skiing area, the story of Bolton Valley mountain biking unfolded on the other side of the state and spectrum.

Backcountry skiing in Bolton Valley had been active since the 1920s, sustained by a committed community of local skiers until the resort opened in 1966. Bolton Valley’s backcountry offers a sense of remoteness, drawing many who enjoy the paradox of personal solitude that's only a short drive away.

Sitting at the end of a four-mile access road is Bolton Valley Resort. The ski area caps the top third of 3,100 feet of elevation and saw a mountain bike community take that relief and mold the terrain into a network of technical, challenging and notoriously intimidating trails.

“They were just over my head,” says Adam DesLauriers, son of the ski area’s founder and current co-owner with his sister Lindsay DesLauriers, “I just couldn’t ride them [the trails]. I could maybe get down one.”

In the Northeast Kingdom, the trajectory from skiing to mountain biking was somewhat causal; with one foot in the snow and one in the dirt, mountain biking expanded from cross-country trails into a multi-use system before eventually linking to Burke’s downhill scene. Bolton mountain biking, on the other hand, grew in parallel with the Bolton Valley Resort, maturing as its own gravity-fed animal

Save for a brief play at the cross-country scene in 1990, a few summer lift days and an incidental downhill race in 2004, mountain biking and community trailbuilding continued through the years, marginally encouraged and mostly unimpeded. As the ski area changed ownership and priorities began to shift, the number of trails continued to grow and earn a reputation for their difficulty, which suited the trailbuilders just fine.

“Bolton is unique in that it’s on private land owned by people who didn’t really care about mountain biking, so they [trailbuilders] kind of had free reign,” says DesLauriers. And free reign they took, constructing trails by and for experts, using copious time in the woods to push their craft and their limits, at one point incorporating a promotional bus into a jump.

But after those initial efforts in the mid-90s and early aughts, the Bolton biking community was distilled into a committed handful of hardcore riders and trailbuilders constructing gnarly lines who were devoted to keeping what they’d started going.

By 2017 the DesLauriers had moved back to Vermont as passionate mountain bikers and, with the backing of an investment group, brought ownership of Bolton Valley back under the family name.

“We talked it over with the family [including brother Evan and father Ralph] and decided we wanted to make a move for the summer—to make Bolton Valley year-round again,” DesLauriers says, “So we thought, ‘OK, what are Bolton’s strengths and how do we make this more mainstream?’”

The popularity of nearby networks showed the DesLauriers that less-experienced riders were eager—but. possibly not able—to ride Bolton. Unsurprisingly, a network built in the spirit of personal one-upmanship didn’t offer much in the way of incremental progress. So the DesLauriers went to their investor group with a proposal for constructing beginner and intermediate trails to attract new riders to the mountain. The answer they received wasn’t what they’d expected.

“They came back to us and said, ‘Think bigger,’” DesLauriers says. “Like, go for it.”

With the existing trails acting as proof of concept, the Bolton team brought in Gravity Logic, started a capital project and built a whole park. Despite the unapologetic burliness of many of the system’s original trails, the team found it didn’t take much to make them more approachable.

As a ski area, Bolton Valley has made community the cornerstone of its philosophy. Families return every year, some with second-generation Bolton skiers teaching the third on the same slopes they themselves learned.

“I definitely don’t think these trails would have developed without the ski area,” DesLauriers says. “Without the access road it’s just too much of a climb, and there’s other great riding nearby. Now there are a couple networks really close by and I don’t have to drive three hours if I want to ride.”

After a decades-long ascent, Bolton Valley’s mountain bikers have finally let off the brakes to enjoy the turns they’ve earned.

Having grown up in Buckland, Massachusetts, Angus McCusker gave his heart to downhill skiing until his affinity for constant movement and solitude brought him to the dark side, and cross-country skis became his planks of choice. Years later, McCusker found himself in the backcountry scene exploring ways to connect moose meadows—clearings on the mountainside ideal for carving turns—into longer skiable lines. He helped form the Ridgeline Outdoor Collective, or ROC (then known as the Rochester/Randolph Area Sports Trail Alliance), in 2013 and now serves as its executive director. The organization’s first initiative was to establish a fully sanctioned backcountry ski area.

“The Forest Service had to put out the call across the country—like, has anyone done this?” McCusker asked, recalling the project. “It turns out they really hadn’t, so this really became the first pilot backcountry program of its kind.”

Once armed with the go-ahead to build ski lines at nearby Brandon Gap, ROC opened its first zone during what turned out to be a terrible winter. Snowfall improved the following season but, to McCusker, the writing was already on the wall: “We were just a few decades late with climate change and everything.”

Fortunately, most skiers and riders in the community were also mountain bikers and, since McCusker had already worked with land managers on the ski area project, the relationship was established for summer trail development.

Mountain biking and skiing are prevalent in Rochester, with access to both sports developing largely in tandem. Like other areas, the town was adversely affected by funding issues that prompted school consolidations across the state. Unlike other small Vermont towns, it also boasts a popular youth mountain biking program.

While other regions channeled community enthusiasm into trail planning and network development, Rochester flipped the model, channeling trail planning and network development into local enthusiasm.

“At first we kind of did it for ourselves, but we recognized that we could share this opportunity,” McCusker says. “Bringing more people in helps local businesses and the town cafe, but our town isn’t set up to handle big crowds or maintain a big network, and we don’t really want to.”

How do you access big ride miles without maintaining an equally big trail system? For McCusker, the answer is the Velomont Trail, an ambitious project that aims to connect some of Vermont’s most notorious riding destinations. When complete, the multi-community collaboration will be to Vermont biking what the Long Trail is to Vermont hiking. The planned connections are more than trails, they’re links to neighboring communities, to the physical and mental health benefits mountain biking offers and a means by which to engage the next generation of riders whose parents are already making forest access a priority when looking for homes and a place to put down roots.

Mountain biking continues to grow and expand in new and exciting ways, propelled by the same fervor of creativity and enthusiasm that launched skiing to the forefront of Vermont’s identity a century ago.

“I think this the way Vermont is going to adapt,” McCusker says about the future of recreation in the state. “The way Vermont is known for skiing—it’s going to be known for mountain biking the same way.”