When in Poland Slowing Things Down in Central Europe

Words by Steve Storey | Photos by Justa Jeskova

If there’s one thing the Polish enjoy, it’s a good meal.

If there’s a second thing, it’s a grueling bike ride—finished off with a kielbasa, beer and a cigarette, of course.

Coming from the relatively young, sparsely populated country of Canada, Europe has always intrigued me. It’s a place with cafés older than the Canadian constitution, with an appreciation for a slower pace of life and perfectly crafted beer from centuries-old breweries.

And so, on a sunny spring evening in May of 2016, I found myself crossing the border from Slovakia to Poland, accompanied by photographer and Slovakian-turned-Whistlerite Justa Jeskova. The road twisted through quaint villages, small restaurants and bars filling the spaces between the patchwork of cottages. I excitedly pointed out what I thought were ancient castles, and inevitably Justa would inform me each was just a regular building—things are old in Poland. We were here for two weeks: one in Poland, and then to the Czech Republic for the other. Already the landscape was just as I’d imagined.

It didn’t take long for us to be treated to an actual castle. Our first destination, Bielsko Biala, was presided over by a fortress from the 12th century. Legend has it that a group of bandits used a different castle in the area to attack passing merchants (a transgression for which the bandits were inevitably executed). Our intentions were less nefarious. We were there to invade the Beskid Mountains, in search of the area’s storied riding scene.

We arrived in the ancient city after dark, and quickly exchanged our car for bikes to explore the older part of Bielsko Biala. The main square was lit up by breweries, cafés and bars, all packed with families and groups drinking and eating late into the night. The vibrant whirl of history and society soon had me questioning my vow to never live in a city.

Early the next morning we headed to Kozia Góra, a nearby prominence covered in a network of trails. While the eateries in town were closed—Justa informed me most places don’t open before 10 a.m.—at the trailhead we found a much earlier crowd. It was just after sunrise, and yet the parking lot was filled with food stands. The smell of kielbasa pulled in riders already returning from their morning loop, and nearly every meal was accompanied by a beer. Apparently, day drinking—or rather, morning drinking—wasn’t just accepted in Poland, it was encouraged. It was a tradition I could easily get behind.

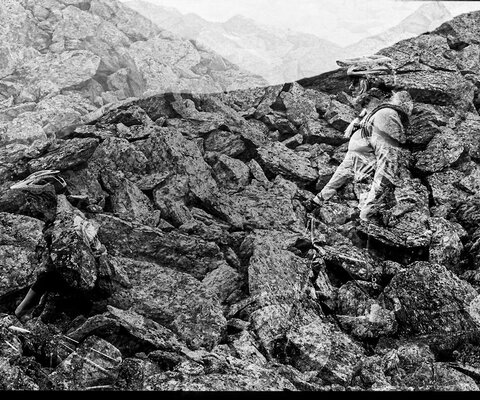

A few days later found us grinding up a nearby 2,000-foot climb. We reached the summit just as a storm moved in, and sought refuge in a massive stone building with a bar and restaurant, already packed with Lycra-clad mountain bikers. Most of the bikes outside were equipped with ancient cantilever brakes and tires barely wider than a road bike, and no one seemed in a rush to bomb back down the fire roads they’d just ascended. Poland has a hardcore community of riders, and while they may not be up on the latest gear or trends, they all love bikes, and a ride isn’t complete without a beer and a cigarette.

The storm passed and we dropped back in, flowing through deciduous forests still layered with leaves from the previous fall. Inevitably, the trail popped out at another café—at which we took another beer break. The views from the deck were huge, the countryside fading off into the smooth horizon of the Black Sea.

After a week in Poland we made our way into the Czech Republic, passing through endless farmland bordered by poppies before reaching the small town of Černá Voda. We pulled up to two old buildings that resembled a hippie commune—that is, if a hippie commune had dirt jumps, pump tracks and an outdoor bar. This is Rychlebske Stezky, a nonprofit riding center headed by Pavel Hornik. The area was constructed with the help of an army of volunteers, and includes an impressive network of trails following centuries-old hunters’ paths. The park has become wildly popular; it’s now visited by thousands of riders each year.

Our lodgings in Černá Voda were a Communist-era hostel, run by an older local couple. The man was rotund, jovial and more interested in talking than working—that was accomplished by his wife, who was clearly the boss and clearly fed up with his conversation. As they argued charmingly, the woman served us beer and dinner, and the dining room filled with a gamut of customers, from local villagers to a group on a guy’s-only bike trip. I was soon lost in the warmth of humanity, listening to the conversations swirling around me. I ordered another beer and kielbasa—when in central Europe, do as the Europeans do, and that means taking time to enjoy where you are.

That, and eat. A lot.