Summits are Overrated Three Decades of Exploring with Hans Rey

Words by Sakeus Bankson

Hans Rey wants to bike on the moon.

OK, so the idea may be a bit of a stretch—NASA turned him down when he asked—but if there’s anyone who would have a chance of making it happen, it’d be Hans. He’s ridden in more than 70 countries. He’s taught a chimp to bike. He counts Tim Commerford from Rage Against the Machine as a riding buddy. He’s appeared on more than 350 magazine covers. He’s bungee jumped into a river on his bike, and President George H.W. Bush shook his front tire.

When talking about someone like Hans Rey, it’s hard to know where to begin. Walking around his house in Laguna, CA, the menagerie of souvenirs crowding the walls read like a world map: masks from Kenya, rocks from near the Great Pyramids, and a life-sized replica of a terra-cotta warrior from his trip to China are a few examples. And that’s just in his living room.

A retro poster of Hans, riding a wheelie and sporting a thrilled smile, hangs above a desk littered with trip proposals and material for next year’s book-sized media kit, which Hans has been making annually for decades. Now at 50 years old, he’s been with GT for 29 years, potentially the longest continual sponsorship in action sports.

From worldwide exhibition tours to appearances on international TV shows to expeditions on nearly every continent, Hans is arguably the best rider in the sport’s history. To the larger world, he was the face of “extreme” mountain biking (a term he coined) in the late 1980s and early ’90s. For hardcore riders, he’s been cited as an influence by the likes of Wade Simmons and Danny MacAskill. As for adventuring, he’s probably surpassed Indiana Jones.

Hans “No Way” Rey has been a lot of things over the past 35 years: multi-time world champion, Hall of Famer, stuntman, entrepreneur, explorer, icon. Whatever his role, he’s remained a biker to his core, whether holding wheelies at the Olympics or hopping around lava in Hawaii. If it involves a bike, there are few things Hans Rey hasn’t done. And he’s not finished yet.

If Hans’ living room is a lesson in geography, his garage is one in mountain biking history. Dozens of bikes hang from the walls and ceiling, with wheels and other old components crammed under workbenches. A fleet of new GTs are lined up around his KTM dirt bike, a mix of trail bikes, a DH rig and even a new trials bike.

As we talk, Hans tells me about his early years in the United States and his theories on the potential alternate histories of the pyramids. He still has a slight German accent, and speaks about his accomplishments frankly. Anyone else might sound slightly arrogant, but to someone like Hans they’re just facts, like Michael Jordan listing off his basketball stats.

Hans’ career began in Kenzingen, Germany. Born in 1966, Hans—full name Hansjörg—and his friends were originally interested in motorcycle trials, which was popular in Europe. Their parents were not having it—too dangerous and too expensive. Undeterred, the kids started modifying their bicycles to do the same style of stunts.

“By 1978 or so, we were imitating moto guys on our bicycles,” Hans says. “We started riding some off-road lines, and then we started making modifications—bigger tires, handlebars, this and that. By ’79, we had 50 guys all riding bicycle trials, all on homemade gear, and the motorcycle club organized a competition for us.”

They found a larger welcome than they expected. Bicycle trials were huge in Europe, and soon Hans was not just competing, but he was also winning. He became the German Trials National Champ from 1982 until ’85, and the Swiss champion from ’84 to ’86. In the meantime, he made extra money doing exhibitions around the country.

“As we grew up, the sport became bigger, and we even got some local sponsorships, like free bikes,” he says. “We were doing shows at different locations—it could be a city fair, a car dealership, or at some other exhibition. We had an official team, and we’d bring props and obstacles and charge folks to watch.

By age 19, Hans had graduated high school. As a Swiss citizen through his father, he still had one obligation to meet: All Swiss are required to take military basic training. Hans retired (for the first time) and put on the uniform. But he stayed on the bike. It turned out some of his commanding officers were cyclists, and they let him continue training. One would even become marketing boss for Hans’s longtime sponsor Swatch.

Hans was also applying for work apprenticeships, luckily without success. “I’m so glad I got turned down, he says, “otherwise I might be a banker now.” Instead, Hans headed to university for marketing and publishing, where he snagged an internship with a German TV station, the largest in Europe. It was there he realized the larger potential two wheels could offer.

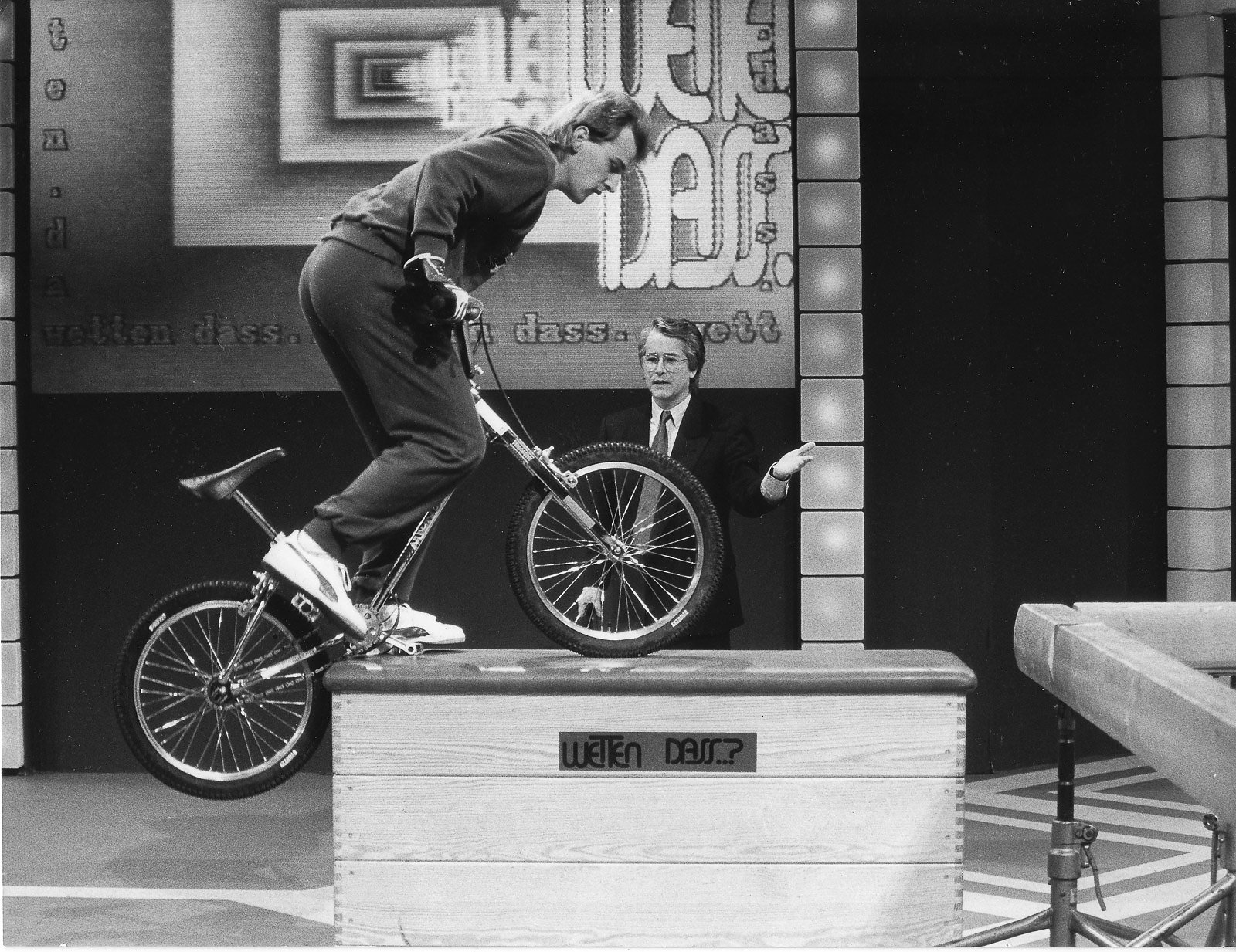

“The show was called Wetten, dass…? Hans says. “It means, ‘I bet you,’ Celebrities would challenge people to do crazy stunts. Somebody bet I couldn’t ride around a square of balance beams. There were some 41 million viewers watching, everybody in Switzerland, Austria, Belgium, Denmark, even East Germany.”

It was 1987, Hans was 20, and bikes were back on his mind. Then he received an invitation from an American trials rider named Kevin Norton, with which he’d competed a few years before in Europe. Norton encouraged Hans to come to California, to try a new form of cycling called “mountain biking.” Hans arranged to take a semester off, and headed to America.

“The race format was every rider doing downhill, cross-country and trials on the same weekend, and overall score would determine the winner,” Hans says. “Kevin said, ‘You have to show Americans real trials. They’ve never seen anything like what you guys do.’ I thought it would be a great end to my career.”

In the United States, Hans found a swirl of different options. He arrived in Laguna Beach—Norton lived in nearby Corona Del Mar—and soon found himself wanting to stay. That idea was cemented when he earned a sponsorship with GT. Then, after only three weeks in the country, Swatch flew him to a photo shoot in New York. The project resulted in the now-famous ad of Hans bunny-hopping on a taxi, and, eventually, a sponsorship that would last 19 years.

But it was mountain biking that had lured Hans across the Pacific, and as a fresh Laguna transplant, he quickly fell in with a local underground crew, the Laguna RADs, one of the world’s first and most hardcore mountain bike clubs.

“The Laguna RADs are the Robin Hoods of mountain biking,” Hans says. “They became known for riding this steep stuff, but the really cool thing was that while many of them raced, they also preserved this original mountain bike spirit. It’s the same as the clunkers and early free riders had, and they still have it today. The RADs made me a real mountain biker.”

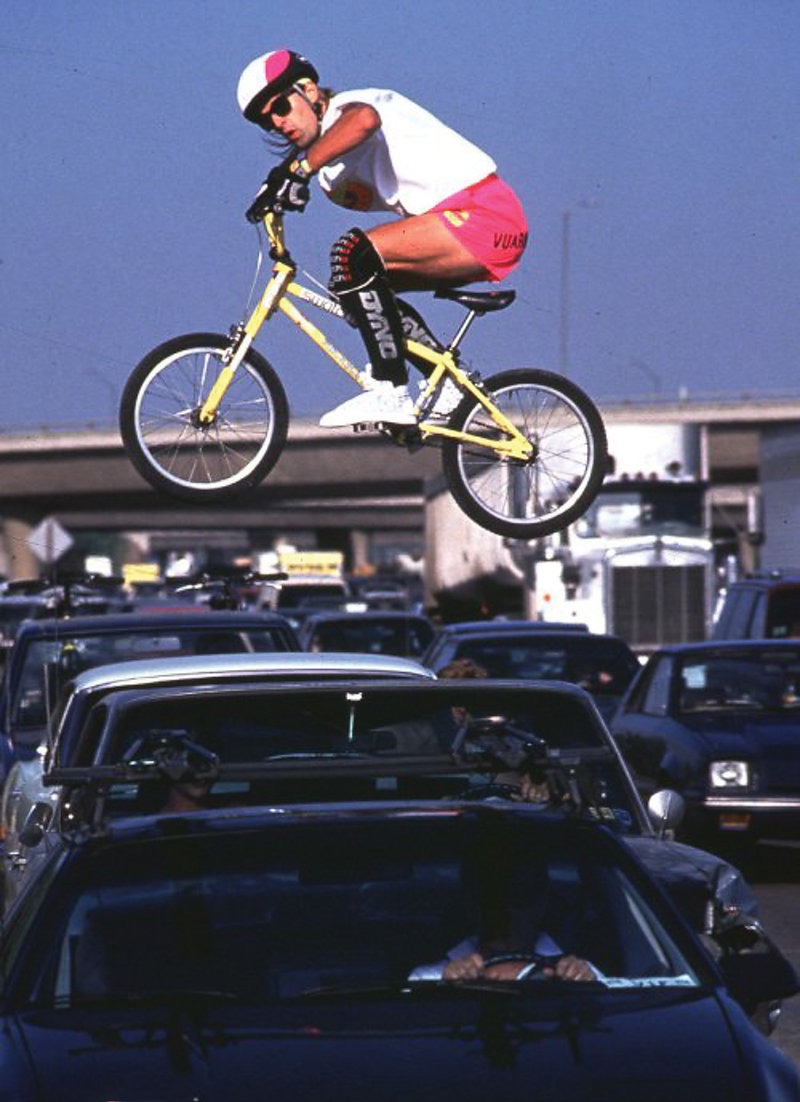

With that, Hans had momentum. In the late ’80s, he went on exhibition tours with skateboard legend Rodney Mullen. He famously bunny-hopped across cars on Interstate 405 during rush-hour gridlock. He was the U.S. Trials champion from 1987 to ’91 and the U.S. MTB Trials champion from 1991 to ’93. Hans became a familiar name at mountain bike downhill and slalom races as well, earning a respectable third place at the UCI Mountain Bike World Championships in 1993 in France.

Perhaps Hans’ greatest foresight, however, was to have vision in the same vein as skater Tony Hawk and skier Glen Plake: He saw the sport’s potential outside its own bubble. It showed in his side projects. In 1991, he was the stunt coordinator for Willy Bogner’s Fire, Ice and Dynamite, a film featuring former James Bond Roger Moore. He rode alongside snowboard legend Terje Haakonsen in Greg Stump’s 1993 classic P-Tex, Lies and Duct Tape. He became his own event organizer, and worked to get himself nonendemic exposure, like when he appeared as himself in the TV show Pacific Blue during the mid-1990s. He even became a member of the Screen Actors Guild.

At the same time, Hans’ interest in racing and competitions began to wane. He had already “retired” once, and was feeling the pressure to go back to university. He was left with the decision to take a different path in mountain biking, or start pursuing other directions (one of these being a professional aggressive inline skater).

The answer came in the form of a collaboration with Richard Long, owner and founder of GT, and would foreshadow the YouTube-style edits that would make riders like Danny MacAskill famous two decades later.

“Richard said, ‘Why don’t we do a video? What you can do on a bike is so hard to explain to anybody,’” Hans says. “And so we did, and called it Hans ‘No Way’ Rey. At the time, videos were usually over an hour long. No Way was short, like 15 minutes, and it left people hungry. They wanted to see more, and they watched it again and again.”

Released in 1992, the VHS was an instant success. It was one of the first videos focused on a single rider, unique in action sports at the time. Hans continued the series until 1996, including the iconic Monkey See, Monkey Do, in which he teaches a chimp named Mr. Jiggs to ride a bike. In another segment, he rides up a waterfall in Jamaica.

The timing couldn’t have been more perfect. Soon after the end of the series, mountain biking saw another surge in popularity, both in racing and as a fledgling “freeride” scene began to emerge. “It was the beginning of the heydays of mountain biking,” Hans says.

Two memorable victories came in 1996, when he earned silver at the inaugural X Games, and was in the “Extreme Sports Act” at the closing ceremonies of the Olympic Games. But, after over 15 years of fighting for podiums, in 1997 Hans officially gave up competition. He had a new vision: Take mountain biking to the edge of the map, and bring viewers along for the journey.

When he retired from competition, Hans was no stranger to travel. Besides Jamaica, he had been all over the world for exhibition tours, movie and photo shoots, and a slew of events. With that experience, combined with inspirations like mountaineer Conrad Anker, Hans realized there may be better ways to connect with regular mountain bikers outside the race world.

“I was always intrigued by these guys who did adventure trips,” he says. “Just like Indiana Jones had a horse or donkey, I would have a bike. I could get further into remote regions than on foot, tying the bike into the whole experience. For me, it made a lot of sense—there were millions of mountain bikes being sold, but only a few people raced. There are so many other reasons why people ride mountain bikes.”

Proving their undying loyalty, GT was right behind him. Long gave him the go-ahead, making Hans’ “Adventure Team” official. Hans became the only permanent member, bringing in a rotating cast of athletes—Steve Peat, Richie Schley, Brian Lopes and numerous others—on trips to places as close as California and as far as Botswana. Often he brought a small film crew to capture the adventure, and the resulting stories have run all over the world, on TV shows, in adventure and mountain bike magazines, even ads for cars.

The tales that have stacked up are endless. A few of the countless highlights include: Searching for a mysterious tribe of dwarves in China; following the path of headhunters in Borneo, where Hans and Peat rode in limestone caves and Hans says he was possessed by spirits; and a first descent of Mt. Kenya, a trip hallmarked by one of Earth’s largest mammals.

“There were elephants everywhere,” Hans says. “Six hours in the country and I saw a fresh-born baby. At camp, there was this famous elephant researcher who told us about a skeleton at 12,000 feet they’d seen from an airplane. Icy Mike, they called it. They wanted a DNA sample to see where it had come from and how old it was. After a whole day hiking on our way down, we were able to find the skeleton and bring back a sample.”

And the trips go on: To Egypt and the Great Pyramids in 2001, where he followed the path of Moses across the Sinai Desert. A circumnavigation of Tanzania’s Mt. Kilimanjaro in 2008 with his wife and professional photographer Carmen Freeman Rey. A trip to Hawaii, where he wheelied next to lava flows. Peru, Ireland, Nepal, Scotland—you’d have to look at his passport to see them all, and each has its own unique value.

“Some trips happen for the sheer beauty of the ride, and the adventure itself—the location, the trails and the people I’m with,” he says. “Sometimes the impacts are more one-on-one. You meet a guy who’s lived his whole life in the Sinai Desert, and says something so wise you think, ‘How do you come up with that? And how, though you’re sleeping in the dirt and aren’t sure what you have to eat, are you so happy and positive?’ You can learn a lot from that.”

It’s not always buff trails and beautiful views. During an attempt on a volcano in the Philippines with Lopes, they were turned away by the terrain and potential lava flows, a mission they called “Classified Unrideable.” Or a trip to Cuba in 2002, where Hans and Tarek Rasouli ended up carrying their bikes for 11 hours over two days. But some of Hans’ best stories come out of those excursions.

“It’s not the misery that stands out,” he says. “I read a quote once that stuck with me: ‘The two most fun things about any adventure is planning it, and bragging about it afterward.’ It’s so true because these trips are hard and discouraging and dangerous.

“But that’s all part of it. In my opinion, it’s not the end of the world if you don’t make it to the top. All those things, the journey and the process of making it happen, are just as important as if you summited. I think that is kind of overrated sometimes.”

If anyone has proven his mettle in the bike world, it’s Hans. He was inducted into the Mountain Bike Hall of Fame in 1999, and his adventures in the years since have kept him relevant through nearly all eras and styles of mountain biking. As I watch him hop through a tricky corner on one of the steep trails behind his house, I can’t help but marvel at the casual, playful grace he displays. And that’s at 50—when Hans started riding with the RADs in the late ’80s, he didn’t imagine he’d be doing this past the age of 30. But it’s taken a lot of hard-won wisdom to get him here.

“There was a time when I would cockily say, ‘I ride anything that anyone rides in the world,’ and meant it,” he says. “Then it was, ‘I ride everything anybody in the world rides twice’—where some guy would try something and luckily pull it off, but would probably never do it again.

“You have this reputation as the guy who can do anything, and you turn into a bit of a Billy the Kid. Everybody wants to see if he has a faster gun than you. For a long time, I would take these challenges, especially if it was something down my alley. But now I use my better senses. If the odds are against me, if there’s an 80-percent chance you’ll crash, I say no. I have too much other stuff going on. It’s not worth it.”

It’s a mindset that has allowed him to continue riding as an athlete 30 years after he “retired” from trials—and not just riding, but as one of the most visible athletes in the sport. And just as his goals have changed, Hans’ thoughts on the sport’s future have evolved as well.

“The last 30 years were dominated by technology,” he says. “I think the market will keep changing, but I think in the next 10 years it will be more important where we ride than what we ride, the quality of the trails. Not just purpose built. I think there is going to be a reversal to natural, old-school trails, away from the perfectly shaped stuff.”

From that belief comes another of Hans’ current projects. As a lifetime bicycle advocate and honorary board member of the International Mountain Bike Association, Hans has always been a proponent of making the sport as welcoming as possible. This is personified in a style of trail he coined alongside Diddie Schneider, called “Flow Country,” which are designed to be fun for every level or type of rider. The first official Flow Country trail was built in 2008 in Livigno, Italy.

“Things have changed,” Hans says. “The old days were great, and the new days are great—purpose-built trails are an example. It opens a whole new world, and I’m glad it’s not always ‘the only way forward is more extreme.’ I think I could get 10 people that have never mountain biked before, and if I had the right trail, I could get five of them to start.”

Hans’ other venture is a charity he and Carmen started called Wheels4Life, which gives bikes to communities in developing countries, particularly Africa. After attending a self-help seminar in the early 2000s, Hans found himself wanting to give something back to the activity that had given him so much. Now, Wheels4Life has donated more than 9,000 bikes in 11 years.

“It’s a drop in the bucket in some ways, but in other ways some of these bikes can change lives,” Hans says. “The whole family, the whole village uses them. The kid goes to school and gets an education, and then becomes a doctor or community leader. All because they had a bike and could go to school.”

The day’s ride finishes with a mellow pedal through Laguna, back to his house for a post-ride beer. Hans has promised to show me some trials moves, and he coasts his current trials bike out of the garage, bouncing his weight to check the tires. His front yard is a mix of monkey pine scattered with large boulders, and as he pops a wheelie next to one I realize it’s more than just low-maintenance aesthetic. He hops from rock to rock on his back wheel, almost bumping the terra-cotta warrior before dropping onto a hidden mini tranny.

Nearly 35 years since his first national championship in Germany, he’s still got it—because he’s still working hard to earn it.

“I always say, ‘The most important thing is to keep throwing wood on the fire,’” Hans says. “I could have stopped at any point and nobody in the bike world would have said it was a huge bummer. But at the same time, if I had, I would have never done the things I’ve done the last 10 years. And I’m kind of curious myself, ‘What’s next?’ I’ve always said I’d keep doing this until it stopped being fun, and it still is.”

Hans doesn’t see an end to the trail just yet, and not just for himself. He’s watching those that followed behind him and seeing them find their own spots in the halls of mountain bike history. After a lifetime spent on a bike, the wheelie-ing legend’s greatest contribution may be the path he blazed along the way.

“I hope I have played a little part in inspiring people to keep going, to do it beyond their prime in terms of performance: ‘This doesn’t have to be over in five years. Hans is still killing it at 50,’” Hans says. “Once you see a guy do something, you realize it’s possible. Then you think, ‘He did it. Maybe I can do a no-hander.’ Then the next guy goes for a no-hander, and it goes from there. But somebody has to do it first, and that’s a big thing.”